2043 - Heroes Return

A vision of the archeofuture

The following post is one of a series of five articles written simultaneously by separate authors who cast a vision of the year 2043. The authors have written their pieces in isolation with no collaboration between them. We would like you to read all five articles and then cast your vote as to which one resonates the most with your vision of the future.

The other authors and their posts are:

Winston Smith (who also wrote a follow-up combining the various entries).

The sudden cacophony of excited grandchildren broke through the wall of sound erected by Beethoven’s 5th, alerting me to my son’s return to the family ranch. I carefully packed away the inertial guidance chip I’d been repairing, disengaged my hands from the haptic rig, pulled the optics from my forehead, blinked a few times as my visual cortex re-calibrated for a macroscopic perspective, and went out to watch the sindir descend from the clouds.

Azadeh and Chloe were already out, keeping the rambunctious little ones back as the single-occupant dirigible settled onto the ground in the cloud of dust kicked up by its turbines. The engines wound down, and the helium blister painted in DeepMine’s black and silver deflated. The sindir’s memory metal carapace flowed open to reveal its exhausted occupant, and before Tom could step out of the passenger bubble Leila, two, and Leif, three, had launched themselves like tiny cannonballs into his arms.

Laughing, and being careful to hold on to the kids, he clambered out of the sindir, his luggage scuttling behind him. Once he was clear, the company car closed its hatches, reinflated, spun up its turbines, and took to the air to drift off whence it came.

Tom was wearing a medical exoskeleton over his orange utility jumpsuit. He’d only been planetside a week, and despite the weak centrifugal pseudogravity of the hab and daily resistance training, he’d be needing the assistance of those whining servos for a while yet.

As careful of her dignity as ever, but her eyes shining with happy tears she couldn’t hold in, Azadeh walked slowly up to him; Tom carefully set Leif and Leila down, and folded her in a long embrace to accept a lingering kiss, before turning to place his hands on Ælfric’s shoulders and praising him for how big and strong he’d become, a credit to his father and his ancestors. The boy beamed up at him.

Ælfric was the only one of Tom’s children that he’d met in person. He’d been gone a long time; Leif, Leila, and new-born Soraya (still down for her nap) had been conceived via IVF. Tom had originally had his sperm frozen in case something went badly wrong out in the deep dark, but if his luck held he wanted to conceive the old-fashioned way and be there for their births. As time had gone on Azadeh had decided that she wasn’t getting any younger and didn’t want to wait until she was old, grey and tired to fill out their family. Children shouldn’t be raised without their father, Tom had said, it’s not good for them; bad enough that Ælfric was growing up without him there. Yes but your father is here, Azadeh had replied, so there’s a man in the house, it’s not like I’m a single mother, they’re not going to grow up gay, I want your babies now. That fight had gone on for months. Chloe and I had been glad when Tom had finally given in to the relentless lioness he’d wed. It brought some peace to the house.

When they were done, it was his mom’s turn to fuss over him, and when he finally disengaged from Chloe’s worried attentions he turned to me. I winced a bit as he crushed my old software engineer-turned-rancher’s hand. “We still use our hands out there, dad,” he chuckled. “It’s only our limbs that get weak.”

His grip might have made my bones squeak, but it was his eyes that troubled me. There was something in his gaze I’d never seen there before. Cold as burning ice, hard as industrial diamonds, distant as the stars. Something somehow savage as the boreal forest but precise as nanolithography.

The man that had returned was undoubtedly my son, but he was not the same as the man that had left.

It was still hard for me to believe that my only son was a first lieutenant with Anglo-America’s main asteroid mining venture. If you’d told me that when I’d been his age, I’d have laughed in your face and asked if it was crack that you smoked. The national space bureaucracies had spent half a century cautiously dog-paddling around in the shallows of Low Earth Orbit, sending out the occasional unmanned probe to snap pretty pictures and measure things that didn’t interest or benefit anyone but a handful of scientists who were mainly interesting in keeping the grant money flowing. Hell, half my friends back then were convinced the original Moon landings had been hoaxed on a sound stage, and those were in the days before AI rendered the datastreams no more trustworthy than rumours picked up at the local watering hole. Those were cynical times. With reason.

If you’d asked me back then what my son would be doing with his life, I’d have said defending the ranch and living off the land if he’s lucky, and getting rounded up, chipped, and stuffed into a hive pod if he wasn’t.

We were all pessimists back then, in the very early days of the Soul War, when we didn’t even realize it was a war, when the species was just starting to notice the vampire squid that had been wrapped around its face since the Bronze Age. Most of us didn’t even realize it had been there that long until much later in the process; even those of us who’d started paying attention figured it was fifty years old, a century tops. In those days the future didn’t seem to contain anything but solar panels, algorithmic control grids, and cricket powder, with the big divide being between those broken enough to look forward to it and everyone else.

Chloe and I had been in the latter group, which was why we’d cashed out of our lucrative finance and software jobs and purchased the ranch, back in the early teens before real estate had skyrocketed out of reach for anyone but the obscenely wealthy. We’d figured the best we could hope for was to stay off the grid, under the radar, and build out a little bubble of semi-self-sufficient Christian sanity far away from the merciless, marching madness of the metropoles.

Turned out we underestimated our species in a lot of ways. We never expected the Soul War to catch like a prairie fire the way it did. We never knew the degree to which our potential had been suppressed by our energies getting siphoned off by the parasite class, or how much would become possible how quickly when all that energy and ingenuity was ours to use again. And we certainly hadn’t known how much technology had simply been kept from us, squirrelled away in black programs where only a few even knew such breakthroughs were possible, let alone that they’d already happened. All in the name of control, which we never really believed we could break free from.

Until we finally started to, and the vicious circle of history started trending virtuous.

Not that it had been all rose petals and honey-wine. Not by a long shot. We’d been a damn sight luckier than others through those years. Luckier than the millions who’d died in the famines, the millions lost to biowar, or the millions slaughtered in the remigrations. Luckier than the ones who had gone mad and killed themselves in various ways fast and slow, painful and pleasant, many with the ready assistance of the murderous old regimes who were only too happy to distribute death by needle … fent, meth, mRNA, or straight-up euthanasia, you could pick any poison you wanted as long as it was poison. The shattering of the old world order shattered minds as it went. Luckier, certainly, than Azadeh, whose entire family had been lost overnight when Tehran was wiped out in the Samson Spasm.

Something like a billion people died over those dark years, one way or another.

The wreckage and ruin we lived through left scars on all of us.

Earth was a haunted planet.

But when the dust settled, it was also, for the first time since before history began, a free planet.

Astronauts might not be nearly as rare as they’d once been, but it still wasn’t every day that a hometown boy came back from a three-year deep space mission to set up a mining claim on a near-earth asteroid, and Tom’s share of the profits – and Azadeh’s capable and aggressive management of that windfall – had made him a wealthy man. So as the date of his return had approached, the local Christian Wive’s Social Society had insisted on throwing a ball in honour of the local boy made good. Any excuse to bring together the young ones in a chaperoned environment, and an inspirational local hero was as good an excuse as any and a better excuse than most.

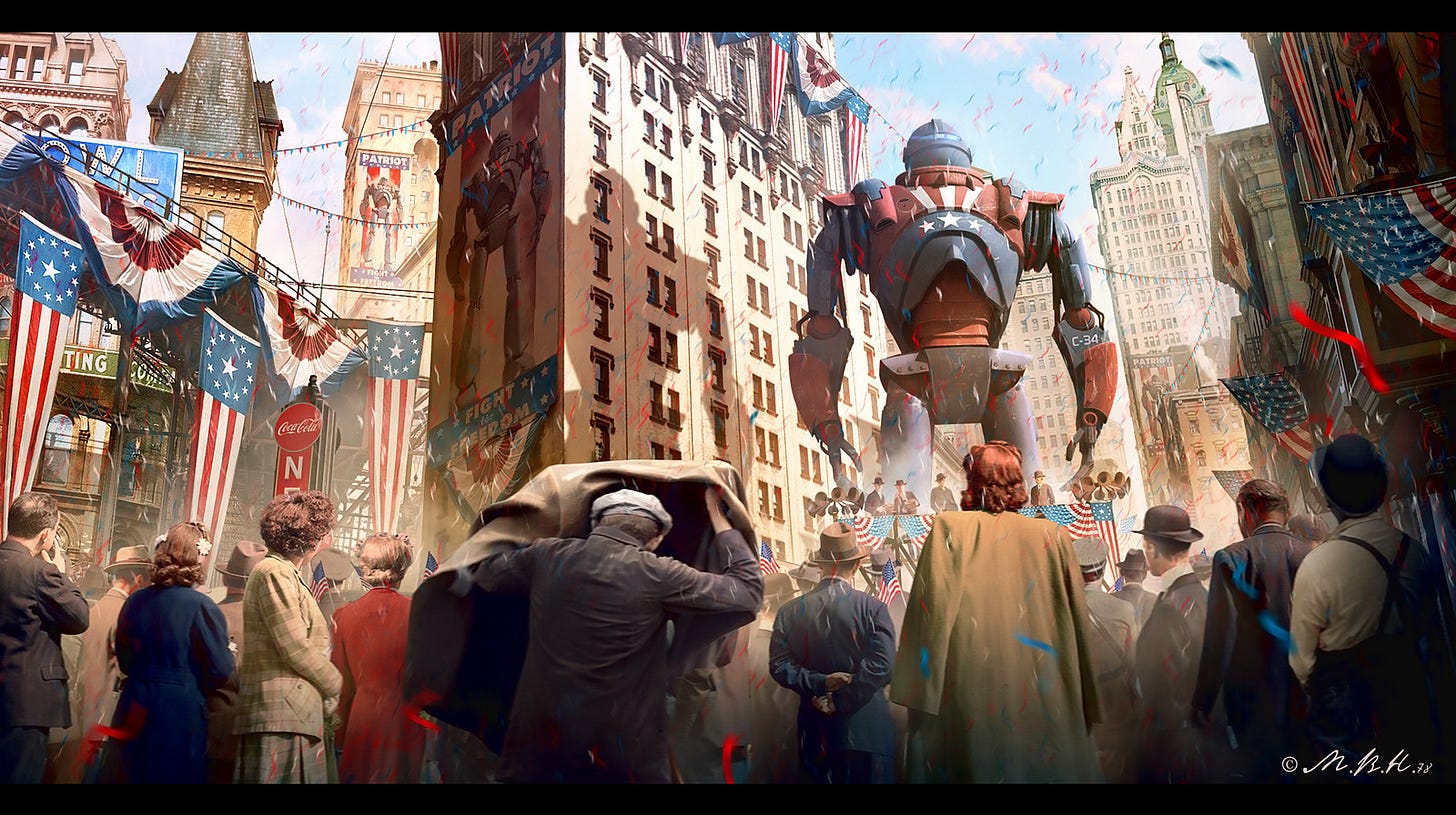

The community hall had been thrown up in a matter of weeks a couple years before, funded with donations from various local enterprises. Watching the construction had been something else. The whole town had come out for the spectacle. I’d taken little Ælfric down to see the team of mechs being lowered from vast cargo zeppelins. The boy had stared with wide-eyed amazement as the titans set about scooping up earth by the ton like they were building a sand castle, pouring out tons of concrete as casually as if they were watering the flowers, and throwing around structural members the size of telephone poles like they were matchsticks. The domed superstructure was up within a few days, after which an army of construction pixies swarmed in to complete the detail work. The boy had been even more amazed when I explained that those hundreds of pixies were, just like the titans, being piloted by tradesmen in haptic rigs all over the planet.

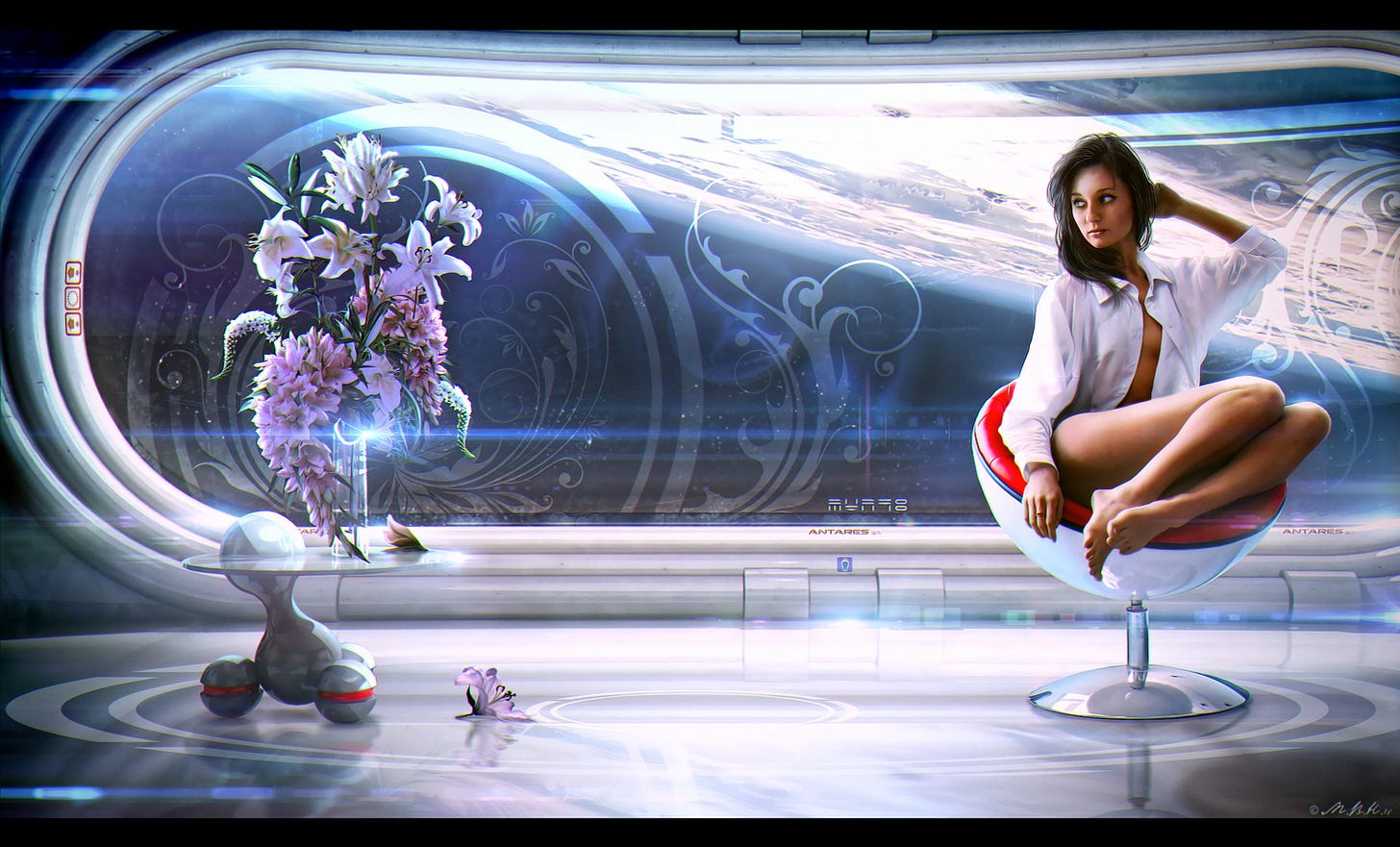

The hall was a broad neoclassical dome of intricately textured azure glass resting on a circle of polished concrete columns. The outer ground level circular wall was inlaid with obsessively detailed 3D-printed frescoes showing a panoramic view of the surrounding landscape, horses and cattle moving through the fields, deer and wolves in the trees, crows and hawks and vultures and cumulonimbus clouds in the air. Inside the walls were patterned to below the human eye’s ability to perceive detail with fractal titanium inlays and fibre-optics, glowing with a soft light that came from a million places at once. An observation balcony circled the main floor, with gently curving staircases wrapping the walls. It was almost too luxurious and fine for our simple town, somehow alien in this landscape of barns, ranches, crumbling warehouses, and boxy strip malls we hadn’t gotten around to demolishing yet, but it somehow managed to blend in respectfully to the landscape, and anyhow this is too nice for a place like this was old thinking in any case. Our towns and cities were becoming beautiful again. We were a new civilization now, and the new architecture – graceful, inspiring, human – was the visible sign of that.

Dozens of whirling couples powered by an energetic electric violin waltz had conquered the polished concrete circle of the dance floor when Tom finally entered. He was resplendent in his high-collared dress blacks, the silver starburst of his rank blazing from his chest, silver piping running down his side and leg, sable half-cape thrown across his shoulder, a ceremonial boarding sabre hanging at his waist. Azadeh was a dazzling ornament hanging adoringly on his arm, her wing-tipped eyes fiery with pride as her animated, chemoluminous hair waved overhead, a golden faravahar inset with an impact ruby spread wide over her bust. Tom had had that custom-made for her, hand-crafted using materials he’d shipped back from a rich vein on Anteros.

The conductor interrupted the dance to announce the guest of honour’s arrival, and there was polite applause, after which Tom was swarmed by local worthies eager to shake his hand. I did my best to beam proudly in the background, trying not to think too hard about how differently this all could have gone. Trying not to think about that unsettling light in his eyes that he’d brought back with him, and what it said was prowling behind them.

Once the local worthies had finished their glad-handing, an athletic dragon scout in the green-and-gold of his order approached the couple at the head of his koryos of wolf scouts wearing their snappy grey-and-whites. The boys were young and awkward enough to be relieved for an excuse to avoid asking the giggling Minervans and Vestans on the other side of the room to dance, although they knew full well it was merely a reprieve. There was about zero chance that the smiling matrons of the CWSS wouldn’t push them together at some point in the night. The kids’ fates were already sealed.

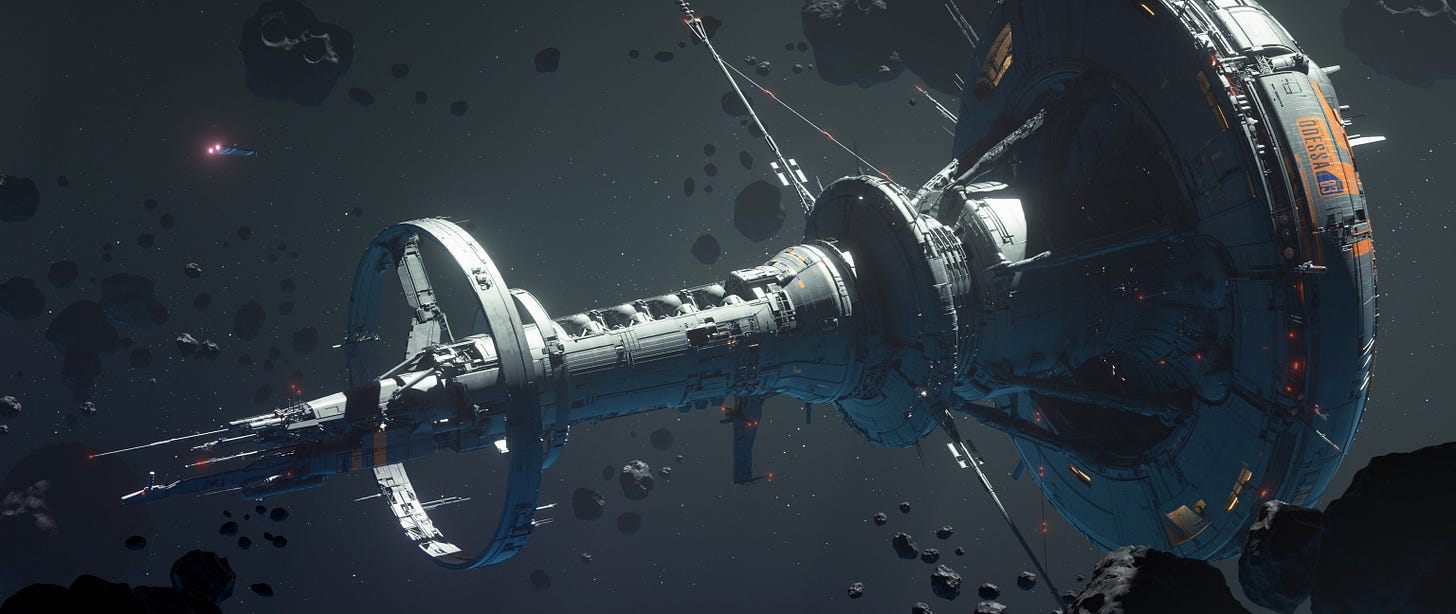

However, that time was not yet now, and the scouts dragged Tom over to the centrepiece in the middle of the dance floor, a 1:1000 scale replica of the Yosemite Sam, the expeditionary vessel that had been Tom’s home for the last few years. The wolf scouts had built it for their aerospace engineering badges; they’d 3D printed the parts from sintered titanium dust which, they emphasized proudly, had come from another of DeepMine’s asteroids. It was impressive work, thousands of intricate pieces comprising the ion engine bells, the engineering neck with its cargo blisters holding mining rigs and supplies, and the hab ring. The latter was slowly orbiting the engineering neck at the same angular velocity as would the real thing, and was kept in place magnetically, also just like the real thing, although the model did the trick using praseodymium instead of a tokamak. There was even a team of tiny animatronic spacers, miming repair operations on the hull. Tom was as impressed as I was, and started pointing out various features on the vessel and asking the kids questions about them, testing their knowledge. Soon enough they were asking him questions of their own. Their eyes shone with the intensity only boys can know when they’re in the presence of a man who smells of distant adventure. His technical explanations evolved by turns into tales of the frozen, radiation-soaked void, the frontier that tested men’s souls as they’d never been tested before. He was evangelizing, and the boys were drinking in his gospel like milk.

Azadeh let him have his fun for a while, before coming over and cutting short his no doubt sanitized account of the robust answer the Yosemite Sam had provided to an attempt by a Han reconnaissance vessel to claim jump, and insisting he grant her at least one dance on this special night. I offered my arm to Chloe and we took to the dance floor ourselves. We let the night carry us along, allowing ourselves to bask in the reflected glory of our hero son, and we let the liquor flow, and to be honest I don’t quite remember getting home.

I do remember getting up in the middle of the night, though. Too much booze and an old prostate.

There was an argument downstairs, Tom’s voice quiet and firm, Azadeh’s hot and slightly hysterical. A slap. A sigh. Tom’s footsteps moving down the hall, a door closing with what wasn’t quite a slam.

Soft weeping.

Thinking better of it but just drunk enough to ignore my good sense, I walked into the room. Azadeh was glaring out the bay window at the night, dabbing tears from her eyes as they carried mascara down her cheeks.

“He’s going out again, isn’t he?”

She startled, glanced in my direction, then turned away. “Bastard couldn’t even wait one lousy day to tell me.”

“You know how Tom is. He’s always been ... direct. Prefers to get the difficult things over with right away. He does it out of love.”

“One year,” she whispered harshly, then spat something venemous in Farsi that it was probably for the best that I didn’t understand. “One stinking year. He already signed the contract.”

“How long?”

She shook her head. “He isn’t coming back.”

“Eh?”

“He’s relocating. He’s taking us with him this time. The whole family. Out there. Says you and Chloe can come too, although he doesn’t think you’ll want to, he knows how you love the ranch. But he’s taking us away. Doesn’t care that I love this place, that this is my home now. Says this is no place for the children to grow up. Too settled, too soft. ‘Out there is where the future is’,” her tone was bitter, mocking. “He wants them to grow up as ‘natives of the sky’.”

I put my arm around her shoulder, gave her the awkward comfort only a father-in-law can provide as she stared out the window, no longer bothering to wipe at her tears. We gazed at the crowded heavens together. Time was, out here, as far as could be from the neon glow of the cities, on a clear night like this, the skies blazed with the stars. These days they buzzed with the bright satellite constellations of orbital industry. Beautiful in its own way, I suppose.

“But you know,” she finally said, a smile reaching into her voice, “It’s been so long since I’ve seen the stars. It would be good for the children to grow up where they can see them, don’t you think?”

I couldn't finish two of the other three I started to read.

I don't know what the future will bring, but if I'm going to read about it, I want it to be optimistic. Because even if the future is dystopian, I am going to meet it head held high and determined to be in good spirits.

Good stuff. I want a prequel where the storming of Area 51 yields memory metal! ;)