Fields and Energy

An interview with physicist, science-fiction writer, and pilot of the aetherwaves Hans G. Schantz

Over the years his research led him to question some basic assumptions about modern physics (for instance, the observer effect in quantum mechanics, the non-existence of the aether), motivating him to conduct one of the most thorough re-examinations of the historical development of physics I’ve ever seen. The fruits of this research project will be available in his forthcoming three-volume work, Fields & Energy. Book I: Fundamentals & Origins of Electromagnetism closed a crowdfund last month and is being sent to backers before a release the first week in December. All of Book I and most of the material from Book II: Where Physics Went Wrong is available already on the Fields & Energy Substack. The trilogy will close with Book III: How Electromagnetism and Quantum Mechanics Work.

Some of the following questions were motivated by Hans’s recent interview on the DemystifySci podcast, which you can see here:

The Rising Tide Foundation also hosted a lecture by Hans, where he explains how to fix physics with fields and energy:

The interview got pretty (really) long, so I’ve broken it up into thematic elements. My questions are in bold. In the spirit of Bottom Line Up Front, here’s the first question:

Can you provide an extremely brief, non-technical, high-level summary of Fields & Energy for the benefit of readers who might not have the background to follow discussions that get down into the weeds of the intersection between mathematical physics, experimental physics, and the historical development of science? What should their main takeaway be?

Physics has long insisted that electromagnetism springs from one paradoxical entity, a photon which somehow simultaneously combines the mutually contradictory properties of non-localized wave and localized particle. My research reveals a simpler truth: two distinct actors share the stage, first fields that move as a wave, the other an energy flow that traces definite paths and appears as particles at the smallest scales. My Fields & Energy model follows from an understanding of electromagnetic theory, yet looks suspiciously like the long neglected pilot-wave interpretation of quantum mechanics. Fields guide energy.

The takeaway is that electromagnetism isn’t just a magic black box where things happen and we can only hope to “shut up and calculate” with tedious formulas. Instead, there’s a deep, rich, and intuitive understanding possible. Electromagnetism is not just math to muddle through, but rather a mindset to master.

A Brief History of Bad Physics

Recently, we’ve been seeing a lot of people, such as Sabine Hossenfelder, saying that physics is broken. Some, such as Eric Weinstein, come right out and say that physics was deliberately derailed into blind alleys. Now, neither Weinstein nor Hossenfelder come off as cranks: they’re fully credentialed physicists, educated at top institutions, but what they have in common is that they’re no longer beholden to the academic system. Would you agree with them that physics is broken? If so, do you think this is historical happenstance, or do you think the waters have been muddied on purpose?

That’s a good question. I do agree with them that physics is broken, but while I think they would argue that this is a phenomenon of recent decades, I would trace the problem back to Mach’s observer-centric approach introduced to physics by Einstein and then brought to fruition by Heisenberg and Bohr. This approach insists on the principle that any attempt to ask how or why something works is out of bounds. The job of physics – in this view – is to mathematically connect a series of measured inputs to a series of measured outputs. Reality is a black box which cannot be opened to understand its workings. Physicists should just shut up and calculate. This is reinforced by a centralized scientific bureaucracy that rewards consensus and often kills genuine innovation.

A Brief History of Bad Physics

How did this perspective become so firmly entrenched in physics? As I read the history of physics, I kept noticing that the biographies of American physicists usually included a line about receiving a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship or grant to go study or work with Bohr at the Copenhagen Institute. In fact, Niels Bohr’s Copenhagen Institute itself was largely funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. And as the situation in Germany and Europe deteriorated in the years leading up to World War II, the Rockefeller Foundation also funded top European scientists to flee Europe and to settle abroad in the UK and US.

Nobel Laureate particle physicist Murray Gell-Mann (1929–2019) quipped that Niels Bohr “brainwashed a generation of physicists….” The Rockefeller Foundation footed the bill. Was this a historical happenstance? Or did it happen on purpose?

The conventional histories and accounts will tell you that the principals of the Rockefeller Foundation merely wished to place their funds in the hands of the best people so they could do good work. A more plausible explanation is that they saw some organizational interest in doing so. I’ve looked, but – so far – I’ve found no smoking guns that might reveal their motives.

I did look in detail at the motivations and confluence of interests behind Einstein’s popularity.

It’s a complicated story, but certainly scientists and scientific ideas are often promoted for reasons other than their scientific merit alone.

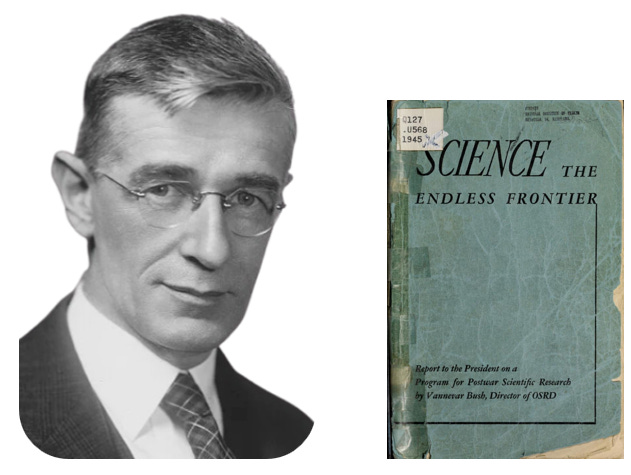

After WWII, science became increasingly under centralized government control. Vannevar Bush (1890–1974), head of the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development during World War II, argued in his 1945 report Science: The Endless Frontier that federally funded basic research was essential for national security, public health, and economic growth. He proposed a permanent government role in supporting science but with research priorities set largely by scientists rather than politicians.

This report directly inspired the creation of the National Science Foundation (NSF) in 1950, institutionalizing federal funding of civilian research. From then on, U.S. science operated in a framework where the government supplied large-scale, continuing support, while also exerting influence through funding priorities, oversight, and classification.

In 1946, the U.S. Atomic Energy Act declared that all nuclear weapons information was “born classified.” The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) reports about 5,000–6,000 patents classified under secrecy orders in force at any given time. Each year, several hundred new secrecy orders are issued and a similar number are rescinded.

It’s entirely possible, as some have speculated, that significant scientific breakthroughs remain behind a wall of classification, while public science is being deliberately allowed to stagnate pursuing unproductive research directions.

Broken Physics

I set out to devise an experiment that could distinguish my Fields & Energy theory from conventional thinking that combines the mutually contradictory properties of particle and wave to a single entity – a photon. One of the classic experiments “proving” the photon theory was the two-slit experiment. In the limit where the source is very dim and only one photon traverses the slits at a time, the individual photons still end up in the interference pattern, proving that somehow a photon interferes with itself, despite traversing only one or the other of the two slits.

What if we secured two separate independent optical sources – like two lasers – and tuned them to the same frequency? If we attenuated them down to the point where only one photon traversed the optical system at a time – from EITHER source – that would show whether fields and energy, whether light waves and light particles were independent or not. If we see interference, then the photon-less wave from one of the sources would have to have interfered with the other to generate the interference. If we see interference from two sources but only one photon, then one of the sources contributed an empty wave. As I started to look into it further, I discovered that the experiment had already been done, and the result was precisely what I’d anticipated.

In 1963, George Magyar and Leonard Mandel used two independent sources and found interferences even with beams attenuated to single-photon levels. Four years later, in 1967, Robert Pfleegor and Mandel carried out a more refined experiment with two independent, frequency-stabilized lasers attenuated to the single-photon level. They observed interference fringes even when only one photon was present in the system on average [Phys. Rev. 159 (1967), 1084].

De Broglie had what I believe is the correct interpretation. He observed, ‘[a] photon coming from one laser or the other and arriving in the interference zone is guided – and this seems to us to be physically certain – by the superposition of the waves emitted by the two lasers…’ [Phys. Rev. 172, (1968), 1284–1285.].

Experimental Proof… Ignored

The Pfleegor and Mandel result wasn’t taken as proving the independence of field and energy, however. In the conventional interpretation, the experiment shows that quantum interference stems from the “indistinguishability of alternative photon paths.”

That’s when I realized how broken physics is. Physicists are so wrapped up in their prior premises, that even what I would think would be a clear experimental demonstration gets interpreted away. It’s not that we don’t have the evidence needed to understand what’s going on. It’s that the evidence we have is being creatively reinterpreted to fit the Copenhagen narrative. That’s why I’m spending so much time on the history and philosophy of science in what should be a straightforward discussion of physics. Unless you can step outside your premises and look at the problem from a fresh perspective, you’ll be forever lost in your misinterpretations.

In Fields & Energy, I’m accumulating example after example that are paradoxical from conventional thinking but easy to understand from the Fields & Energy perspective. For instance, conventional thinking on radiation from accelerating charges models it as “the radiation of one charge accelerating,” a concept that makes no more sense than the sound of one hand clapping.

Broken Science: Antenna Engineering

One more example on how broken science is, this time from the engineering research side. The hot trend in antenna research a couple of decades ago was a concept called “metamaterials.” It was all the rage, and funding flowed in a vast torrent to anyone who could describe their proposed work with a “metamaterial” label. One professor I knew was critical of it, and he told me a bit about the pushback he got. His colleagues were irate. Fortunately, he was retired at that point and didn’t give a damn. But a younger, earlier-stage researcher would be facing a situation in which speaking the truth meant ending his career.

Shut up. Go with the flow. Get funded. Or share the truth, don’t get funded, and jeopardize your colleagues’ funding – colleagues who will be peer reviewing your papers and proposals and might hold a grudge because you threaten their livelihood. Consensus is king, and academia has become a feminized longhouse, as astute observers have already noted.

Academia is Women’s Work

Back in the nineties, when guys still thoughts lesbians were sexy and kids still thought campus was fun, there was a running joke you’d see in college movies. Some hapless dweeb would enrol in a women’s studies course, hoping to get laid. The desperate Casanova’s reasoning was that the overwhelmingly female student b…

The fact that outsiders who aren’t beholden to the orthodoxy of modern physics, like Sabine Hossenfelder and Eric Weinstein, are stepping outside of the longhouse to criticize it is a great thing.

The Hidden Truth

Before you started working on Fields & Energy, you published a series of really wonderful young adult science fiction novels, which I’d recommend to my readers. At the risk of spoilers, these involved a turn-of-the-century conspiracy to cover up certain crucial breakthroughs in electromagnetic theory, which then derailed humanity’s technological development. You then set this series aside to work on Fields & Energy. Is there any connection here?

I suppose you could call it part vacation and part an attempt to try an alternate, unconventional approach to share and promote my ideas. I’d just finished updating my UWB text book, and I was frustrated with how difficult it was to get anyone to pay attention to my ideas — ideas so simple that they were only a modest step beyond what Heaviside and Hertz had written over a hundred years ago. Why didn’t they take that next step? Did someone stop them? Who could have done it and why? I took that as the inciting incident for The Hidden Truth. When I wrote my story in 2016, I was concerned I might place too great a demand on my readers’ suspension of disbelief with the notion of a shadowy cabal suppressing science as part of a campaign to secure global domination. So, I set my story in an alternate timeline with such dystopian concepts as pervasive online surveillance and tech giants rewriting online history to better conceal hidden truths and secure and maintain social control.

I no longer have those concerns.

In The Hidden Truth, my protagonist discovers subtle differences between books in the long-forgotten library in his Appalachian hometown and the online scans. This leads him on a quest to discover who’s changing the past the control the present and rule the future. In A Rambling Wreck, the hero goes to Georgia Tech for his freshman year where he and his friend try to thwart a social-justice takeover of the school. In The Brave and the Bold, he tries to parlay his summer internship into a ticket to Jekyll Island to infiltrate the cabal’s Social Justice Leadership Forum and thwart their plans. The books were fun to write. Eventually, I’ll get around to finishing up the narrative in a final volume. Sadly, although my stories did introduce my ideas to a wider audience, they were only modestly successful. And although I did place an article on my work in in a reputable journal, the traditional academic route wasn’t working for me either.

I had just struck out trying to sell DARPA on my ideas, and I was having dinner with some friends, science fiction grandmaster John C. Wright, and his talented wife, L. Jagi Lamplighter Wright. They asked me “What are these ideas of yours?” I explained. And in maybe twenty minutes, they got it. That’s when the light bulb turned on for me. It wasn’t that my ideas were so complicated that they were too hard to understand. My problem was that professionals indoctrinated in the bad premises and misconceptions of modern physics had trouble setting those ideas aside to consider a novel approach. I decided on a new approach. I’d write an introductory level book to reach out to beginning students, curious laypeople, and those physicists and engineers interested in a fresh perspective on how electromagnetism and quantum mechanics work. I started my Fields & Energy Substack to serialize my work when the rough draft of my book was done. I set aside fiction to pivot toward a non-fiction approach.

The engagement here has been phenomenal. I have over 3000 subscribers, and their feedback has led me to substantially expand upon my original scope. There’s been enormous interest in how physics went wrong, and my most popular posts have been the ones where I’ve tackled that question.

The bad news is that it’s slowed me down. Fields & Energy has now grown to a projected three volumes. I just completed a successful crowd fund for Book I: Fundamentals & Origins of Electromagnetism. I’m in the process of fulfilling it now, and the book will be available for general release in a couple of months. The material is all on my Substack, if you don’t want to wait to see it in book form.

In your sci-fi novels, and again I risk spoilers here, the antagonists are in possession of a tool that somehow enables them to detect the space-time loci of significant events, by means of which they can manipulate the timeline as it unfolds. Exactly how this works is never really explained, but I found the concept quite fascinating for its novelty. How does this device work? Or is the secret behind this device going to be explained in forthcoming novels?

Hugh Everett III (1930–1982) proposed the Many-Worlds Interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics in 1957. The prevailing Copenhagen Interpretation held that a quantum system exists in a superposition until observed, at which point the wave function “collapses” to a definite outcome. Everett rejected the need for collapse, instead suggesting that all possible outcomes of a quantum event are realized, each in a separate, branching universe. Thus, when a measurement is made, reality “splits,” and every potential result actually occurs in its own parallel world.

The MWI multiplies realities extravagantly without empirical evidence. It’s an extreme solution to the problems posed by quantum mechanics, and I think that the pilot wave approach is more reasonable. Despite these philosophical and scientific challenges, MWI makes a powerful storytelling device: it naturally supports the idea of parallel universes where every choice or chance event leads to a branching world. This provides fertile ground for exploring “what if” scenarios, alternate histories, and examinations of what could have happened if characters had made different decisions or faced different circumstances. I make use of the concept in The Hidden Truth series.

My premise is that minor timeline splits happen all the time without any significant impact. Often, extremely similar timelines merge back together with none the wiser. Occasionally, however, a few hanging chads go one way or another, and we get a different president. Or a complicated terrorist attack itself gets hijacked in an unexpected way, the White House is destroyed, and President Lieberman has to carry on as best he can.

Major splits can be detected by a change in the neutrino flux density, in my fictional science. There’s an archaic Chinese approach that uses a “Rod of Destiny,” a long jade-like crystal that glows when aligned with the source of the inciting incident for the impending split. My hand-wavium explanation is that mildly radioactive dopants in the periodic crystalline structure serve to focus the neutrinos and make the crystal fluoresce. At the conclusion of The Brave and the Bold, the hero discovers where one such Rod of Destiny was hidden many decades ago, and Book 4: A Hell of an Engineer will open with an Indiana Jones/Tomb Raider adventure to retrieve the Rod of Destiny, an operation that (of course) goes seriously awry.

I run wild with the idea in my novella, Split Decision, available for pre-order. Set a decade after the main series ends, the hero, Peter Burdell, now operates the principal multiverse portal on his home timeline. When a distress call comes in from his alternate self on a parallel Earth ravaged by a nanotech plague that turns people into zombies, Pete has to ride to the rescue.

Fields, Energy, Pilot Waves, and the Aether

Most of my audience probably doesn’t have much of a grounding in physics, classical or otherwise. So, for the benefit of those who haven’t solved an equation since high school, so that they can follow the discussion along, can you provide concise, non-mathematical definitions of ‘field’ and ‘energy’? How does your understanding of fields and energy differ from the mainstream understanding?

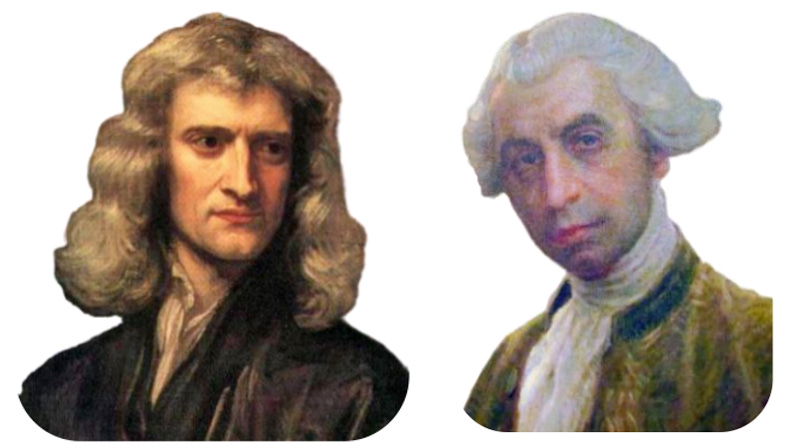

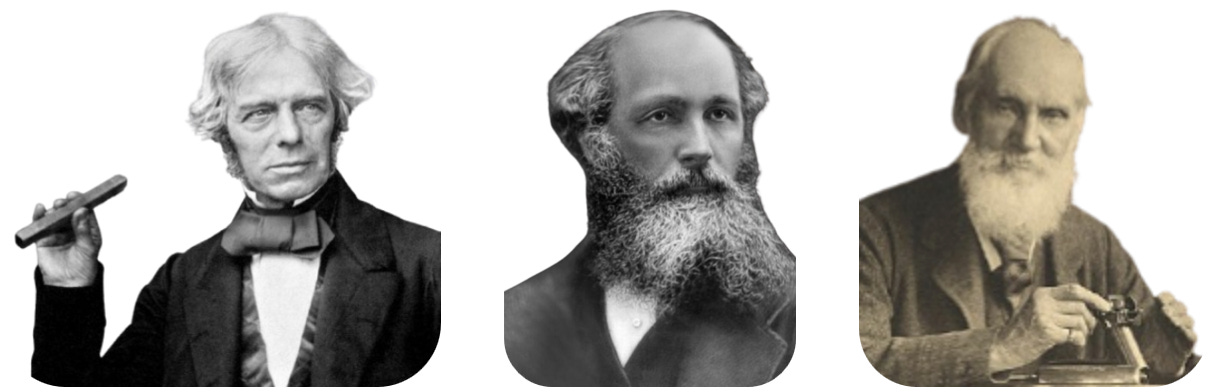

A field describes how influences extend through space (and time). Before Isaac Newton (1642–1727), forces were thought to act only by contact. After Newton, gravity seemed to reach across emptiness. Nineteenth century physicists, led by Michael Faraday (1791–1867) and James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879), gave that “action at a distance” a more concrete form: the field. A field assigns to every point in space (and time) a possible influence: a direction in which it points, and a magnitude. An electric field describes the force that would be felt by a small “test” charge – too small to significantly perturb the field. The magnetic field describes the force on a moving point charge, except the force is at a right angle to the field and to the velocity of the charge. Fields are a map of how the world might act on charge. In this sense, a field is both a mathematical convenience and a description of how the very fabric of physical reality behaves.

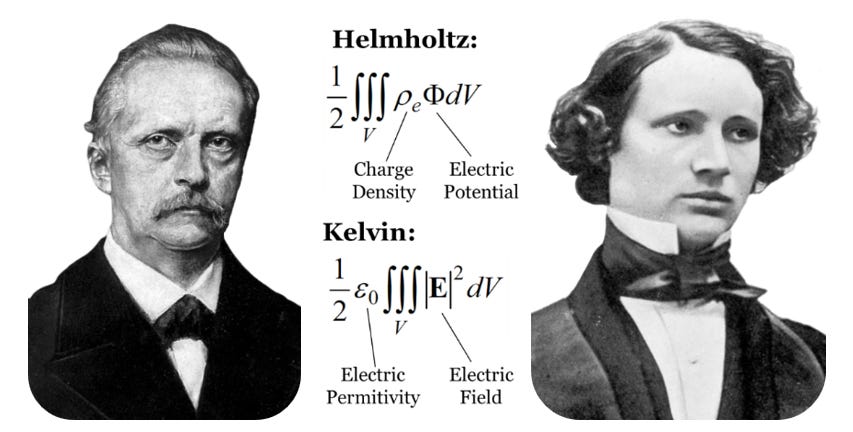

Energy is a capacity to do work, or a measure of ability to cause a change: moving, or heating, or transforming an object. The word itself came into science in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1894) formalized this idea in 1847, showing that despite these transformations, the total amount of energy remains constant: it can change form but is never lost. In his words, energy is “a quantity which nature preserves in all its changes.” Ironically, this fundamental physical discovery was so unorthodox that Helmholtz could not get it accepted by a mainstream physics journal. Instead, he had to self-publish and distribute his paper himself.

Helmholtz defined the electric energy at a point in space as the product of the charge density and the potential. In this theory, as two charge distributions interact, they exert forces on each other. In the application of these forces, one charge distribution loses energy while the other gains energy. From the action-at-a-distance perspective, energy vanishes in one place and instantaneously reappears in another.

In 1853 William Thomson (1824–1907), who would later become Lord Kelvin, came up with an alternative way to define the electric energy. In Thomson’s approach, electric energy is proportional to the square of the field intensity. Helmholtz’s theory suggests energy is co-located with charges. Thomson’s theory suggests that electric energy resides, not in charges, but rather in the surrounding space, making it easier to imagine that energy might be able to flow from one place to another.

The two theories are mathematically equivalent, and both correspond to the results of the measurement. However, they have profoundly different physical interpretations. Helmholtz presents a picture of energy disappearing someplace and reappearing elsewhere. Thomson describes a continual progression of energy from one region of space to an adjacent region, and so on to some ultimate destination.

That intuition would be further developed by James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879) and brought to fruition by Oliver Heaviside (1850–1925) and John Henry Poynting (1852–1914) who developed the theory of electromagnetic energy transfer in free space.

Fields are waves. They propagate at the speed of light in a distributed fashion throughout the surrounding space. Energy is localized. It moves from point to point in a way that’s governed by the fields in its vicinity. In most conventional thinking, the fields and energy move in lock step: a certain individual field moves together with its associated energy from one point to another. That’s certainly the case for an individual isolated field propagating at the speed of light in free space.

Just as a mechanical wave requires a balance of potential and kinetic energy, an electromagnetic wave needs a balance of electric and magnetic energy to propagate at the speed of light without distortion. In free space, the ratio between the electric and magnetic fields, a quantity called the impedance, must be 376.7 ohms for that to take place.

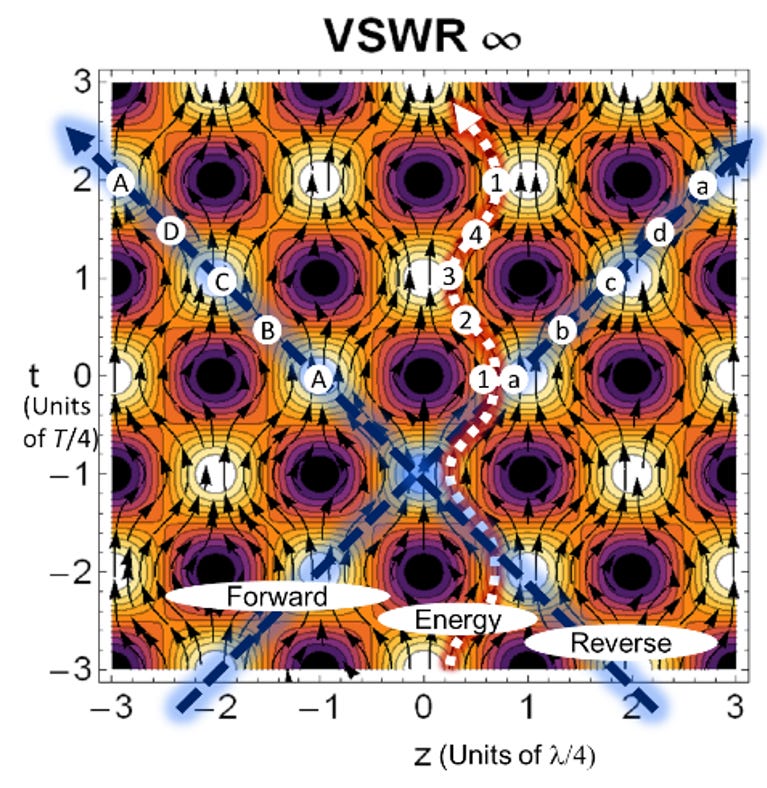

Everyone agrees in the case of one field, or one wave: fields and energy move together in synchronicity at the speed of light. I asked, “what happens when there are two?” That’s where things begin to get really interesting. As two fields or waves interfere with each other, they upset the balance of energy. In a constructive interference, the energy slows down and becomes electrostatic. In a destructive interference, the energy slows down and becomes magnetostatic. In a special case where we arrange equal and opposite waves to pass through each other, they exchange energy. The forward wave ends up with the energy originally in the reverse wave and vice versa. The energy “bounces.” The fields pass through each other. Fields guide energy, but they are independent phenomena that have different behaviors and different space-time trajectories through our physical systems.

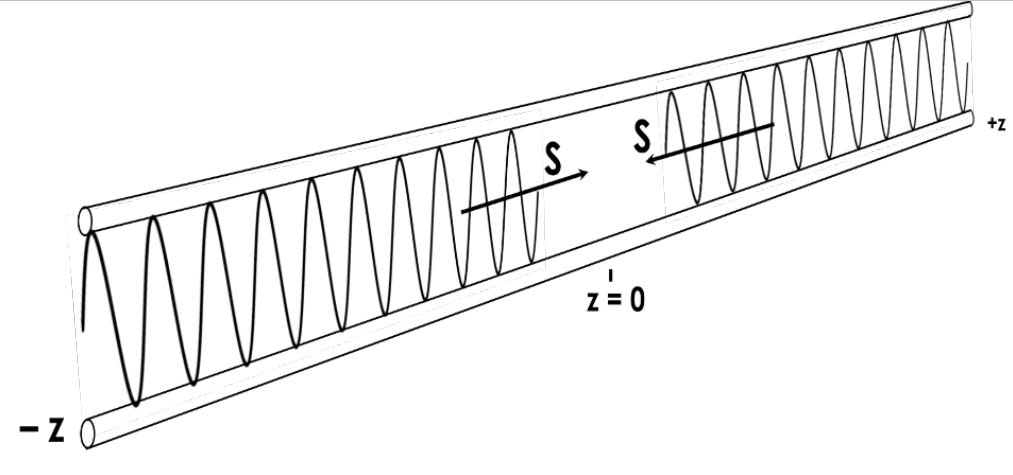

Suppose we have two equal and opposite electromagnetic waves of a particular frequency and wavelength propagating in opposite directions along a transmission line.

We can observe what’s going on using what’s called a “space-time diagram.” We plot the distance along the transmission line, z, along the horizontal axis, and we plot the time on the vertical axis. The forward and reverse waves pass through each other at the speed of light. The axes are scaled so that things moving at the speed of light have a slope of one.

In 2011, Gerald Kaiser drew attention to this fact, noting that although equal and opposite sine waves convey no power on average, they do exhibit oscillations of electric and magnetic energy. At one moment, we have a constructive interference with nodes of electrostatic energy spaced every half wavelength. A quarter period later, we have a destructive interference with nodes of magnetostatic energy spaced every half wavelength and offset by a quarter wavelength.

Although the forward and reverse waves are propagating through each other at the speed of light, the energy is sloshing back and forth a quarter wavelength or so between the electrostatic and magnetostatic nodes.

As I looked into this behavior further, I realized that classical electromagnetic energy flow looked suspiciously like the pilot-wave theory. I’m convinced that the pilot-wave interpretation of quantum mechanics, or something very much like it has to be the underlying picture of physical reality.

Can you quickly explain what pilot wave theory is, and how it differs from other, more popular interpretations of quantum mechanics?

Quickly? Probably not. But let’s start with the conventional or Copenhagen Interpretation.

The Conventional Interpretation of the Two-Slit Experiment

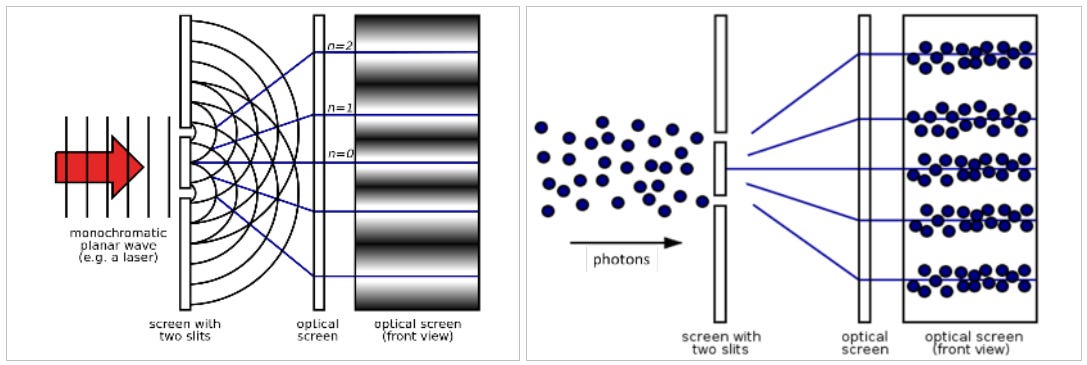

Suppose light is incident on two slits. Waves from the two slits generate an interference pattern of light and dark. The energy is quantized in discrete little lumps called “photons.” Even if the light is so dim that only one photon passes through the slits at a time, we still observe the interference pattern.

If we leave both slits open, the wave-like nature of light manifests itself in the interference pattern of light and dark zones. This happens even in the limit where we can be certain that only one photon traverses the system at a time. By measuring the wavelike nature of light with both slits open to detect the interference pattern, we destroy the particle-like description of knowing which particular slit the photon traversed.

If we try to measure which slit the photon traverses by putting detectors on the slits, we can do so, but of course that destroys the wave-like behavior of light from the interference between the two slits. Try as we might to detect the particle and wave-like behavior of light at the same time, we cannot do so. It’s one or the other.

In the standard “Copenhagen Interpretation” of quantum mechanics, the wave function describes the time evolution of the system. In our example it might predict the photon will be detected in one slit or the other with 50% probability, but that detection collapses the wave function and ends the experiment. If instead we allow the experiment to continue, the wave function continues to evolve until the photon could be anywhere along the screen, but much more likely to be in a bright band instead of a dark band. At the moment the optical screen detects the photon at a particular place on the screen, the wave function collapses to yield that result.

Here’s the problem. A detection or measurement anywhere collapses the wave function everywhere. Simultaneously. Faster than the speed of light. And that was Einstein’s fundamental issue, because the speed of light is supposed to be the absolute limit information in particular or physical effects in general can propagate. Quantum mechanics is “non-local.”

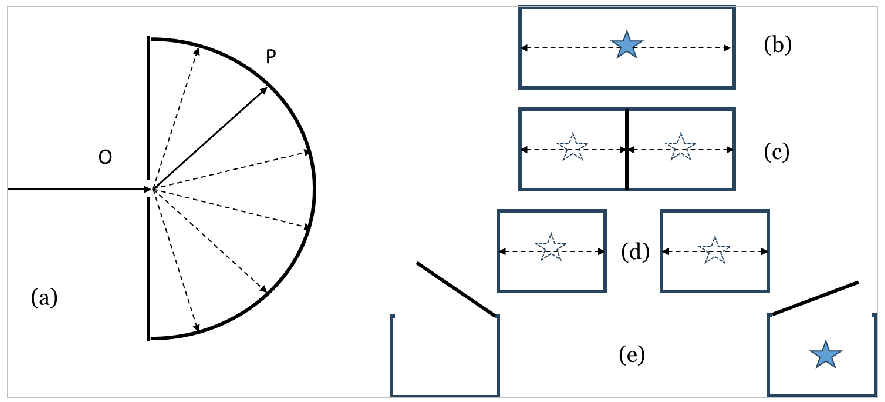

Einstein’s Boxes

We don’t need two slits to be confused by this problem. Consider an even simpler experiment. Suppose a photon diffracts through aperture “O” in Figure (a). The wave function spreads out in all directions until the quantum wave function fills the entire half space. The photon is then detected at point “P.” At the moment of detection, the waveform collapses to zero instantaneously throughout the half space. This instantaneous change is necessarily faster than light and the waveform collapse occurs simultaneously even though the cause (at “P”) is non-local with respect to the effect (everywhere else).

Einstein’s objection comes in sharper focus when considering his “Gedankenexperiment” (or thought experiment) that philosopher of science Arthur Fine (b. 1937) dubbed “Einstein’s Boxes.”

Suppose we place an individual photon (denoted by a star) in a reflective box as in Figure (b). We know the photon is in the box, but we don’t know exactly where. Then, in Figure (c) we split the box in two with an additional reflective divider that allows us to split the box in two separate boxes as in Figure (d). The wave function occupies both boxes with equal probability density, and the photon itself could be in either box. Then in Figure (e), we separate the boxes a great distance. We open one of the boxes. It’s either in the box we opened, or it isn’t. Thus, we discover which box holds the photon, ours, or the distant box. At the instant we examined one of the boxes, the wave function has collapsed in the distant box as well, even if it is arbitrarily far away and any message or information traveling at the speed of light has not yet arrived.

Three Key Issues: Realism, Causality, Locality

Realism is the philosophical position that physical objects or systems possess well-defined properties or characteristics independent of measurement.

Causality is the concept that every event has a cause and that the cause must precede the event. If we accept the quantum wavefunction as a physically real entity, distant waveform collapse is a violation of causality.

Locality refers to the closely-related principle that the causes or influences of events must be nearby in space as well as time. In practice, “nearby” means that the influence of the cause can propagate no faster than the speed of light before arriving to give rise to the effect.

Einstein’s Boxes violate all three of these principles. The photon lacks a well-defined position until we open the boxes to observe in which it resides. The act of opening one box and discovering it empty instantaneously collapses the waveform in the other arbitrarily-far-away box, in violation of both causality and locality.

Perhaps that’s just how quantum mechanical theory works, but suppose the theory were “incomplete.” Suppose in addition to the emerging theory there were additional “hidden variables,” like the actual location of the photon, that exist independent of the quantum calculations. In other words, why couldn’t the photon have been in one box or the other all along? Why couldn’t our observations made by opening the boxes merely update our knowledge instead of somehow updating reality itself? If we find a particle someplace, that’s because it was there all along. Right?

“No,” says the conventional Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory. From the conventional quantum mechanical perspective, the act of observation itself collapses the wavefunction and forces the particle to be in a particular definite place. But what’s wrong with the hidden variable concept and why couldn’t the particle have had a definite location all along?

The Pilot Wave Interpretation

In October 1927 at the Fifth Solvay Conference on Electrons and Photons, the same venue at which Bohr, Heisenberg, and their coterie popularized their “spirit of Copenhagen,” Louis de Broglie presented a clever new idea. De Broglie supposed that particles are discrete objects with discrete locations. In the case of the two-slit experiment, a wave guides the light particle, or photon. The wave traverses both slits and interferes with itself. The resulting wave motion and interference pattern guides the photon through one of the slits. “In my hypothesis,” de Broglie explained, “the wave in a way ‘piloted’ the corpuscle, hence the name of ‘theory of the pilot-wave’ which I gave to this conception.”

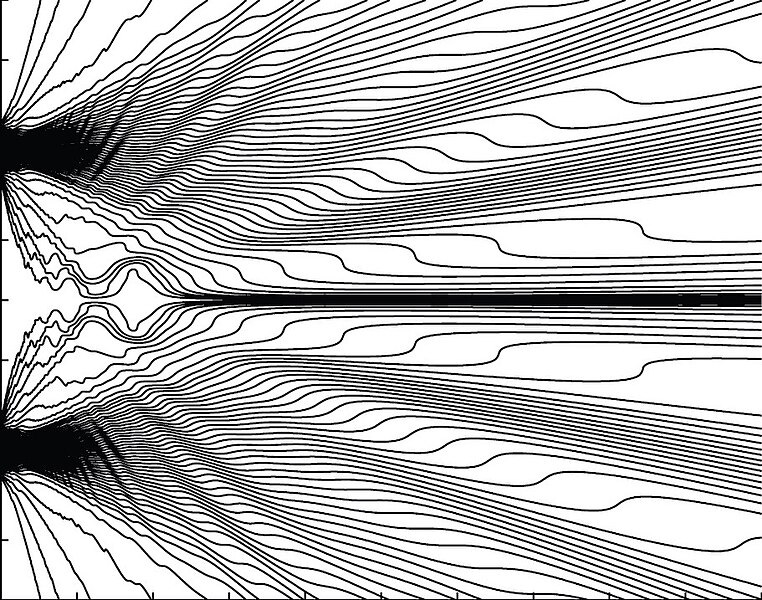

Here’s a calculation of the trajectories an electron might take through two slits.

The paths may appear counterintuitive, swerving one way or the other as they converge in the interference maxima and diverge away from the interference minima. Nevertheless, they tell a story of the definite position of the particle at all times as it traverses our system. Which slit did the electron traverse? The top slit, if it were detected in the top half of the detection screen, and the bottom slit, otherwise. The location where it was detected allows you to figure out which of the paths the particle must have taken to get there.

Facing intense opposition from the Copenhagenists however, de Broglie was persuaded to renounce his idea in early 1928. In 1932, the brilliant mathematician, John Von Neumann (1903–1957), swept aside this commonsense hypothesis, claiming to have proven that the “hidden variable” approach was untenable. Grete Hermann (1901–1984), a German mathematician and philosopher, almost immediately pointed out flaws in Von Neumann’s proof, but her work was ignored for decades. Von Neumann was presumed to have settled the issue once and for all. De Broglie’s pilot-wave approach was resurrected by David Bohm (1917–1992) in the 1950s, but didn’t gain much traction then, either.

In 1952, Einstein wrote to his friend Max Born (1882–1970), “Have you noticed that Bohm believes (as de Broglie did, by the way, 25 years ago) that he is able to interpret the quantum theory in deterministic terms? That way seems too cheap to me.” In fairness, pilot-wave theory may resolve the problems of causality and realism, but it is still non-local. The behavior of particles in one place changes the overall wave function and instantaneously impacts the behavior of particles elsewhere.

The pilot-wave interpretation (de Broglie–Bohm theory) is internally consistent and reproduces all quantum predictions, but it faces objections of taste and technical challenge. It is explicitly non-local, making it uneasy to reconcile with relativity, and its extensions to quantum field theory and particle creation remain difficult. Ontologically, it posits both particles with definite positions and a universal wave function in high-dimensional configuration space, which some see as redundant or metaphysically strange. Since it yields no new experimental predictions beyond standard quantum mechanics, many physicists dismiss it as unnecessary, though others value it for restoring determinism and a clear realist picture of microscopic processes.

Can you explain for the readers how an antenna actually works? How does this relate to your understanding of the æther?

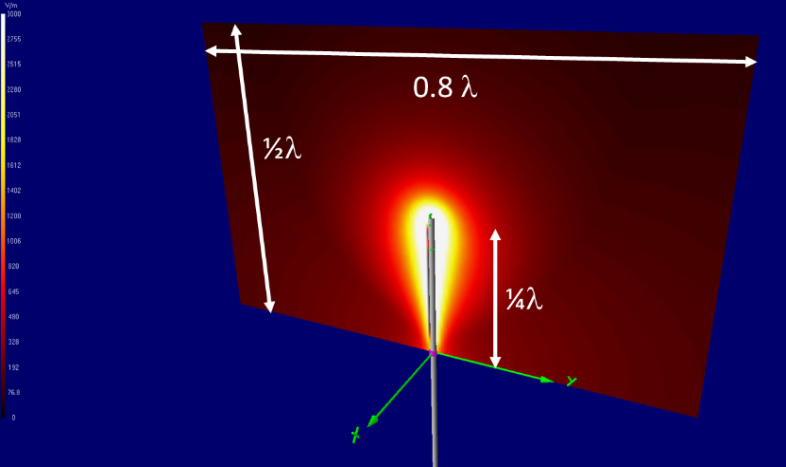

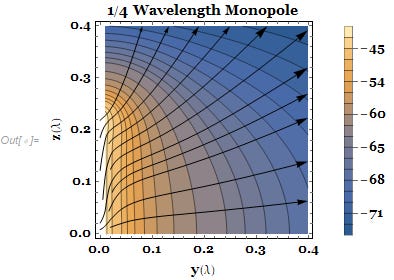

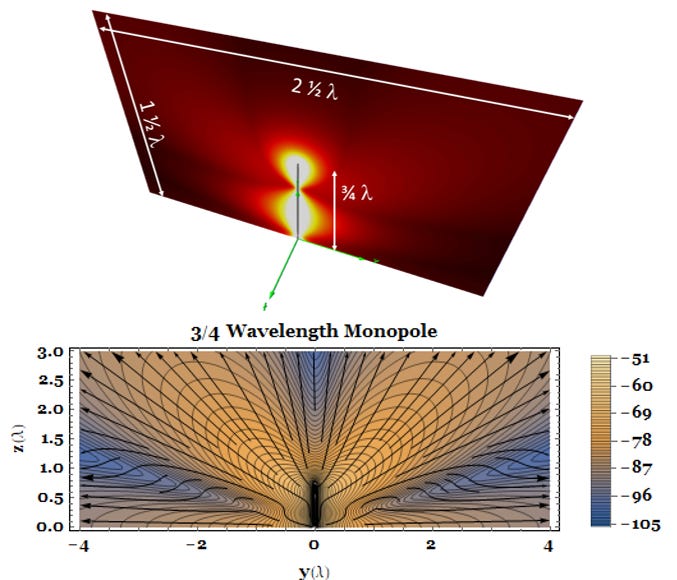

Sergei Schelkunoff (1897–1992) and Harald Friis (1893–1976) pioneered the art of calculating energy-flow streamlines in their 1952 text, Antennas: Theory and Practice. At least, I think they did, because I have found no earlier presentation. There have been other instances where they presented “well-known” results without citation that I tracked down earlier, however. Anyway, Schelkunoff and Friis showed that as energy radiates away from a conventional thin-wire quarter-wave antenna, the element guides the energy flow and distributes it across the far-field pattern. Energy flows along the antenna, before decoupling and radiating away.

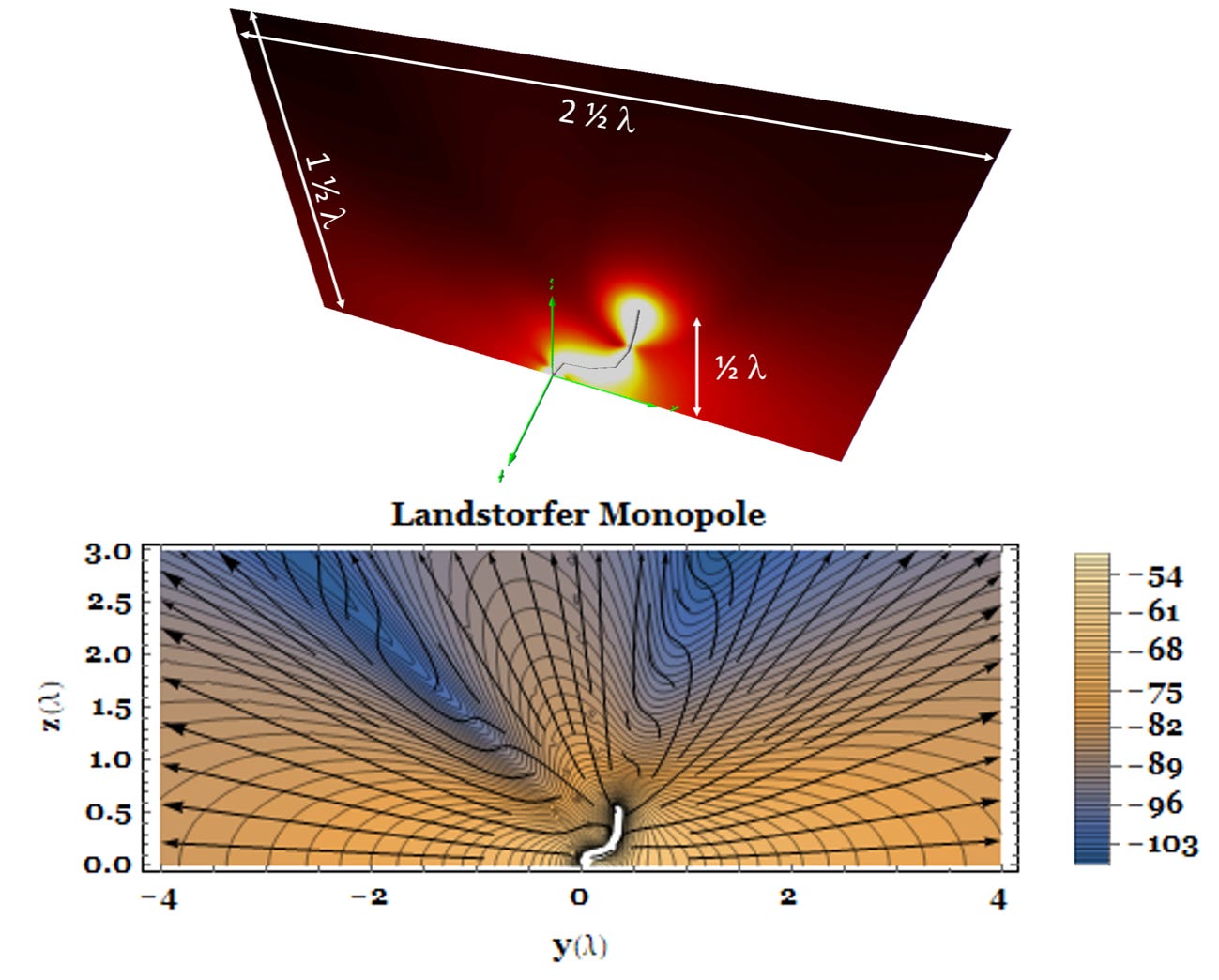

Here’s a more interesting example, first devised by Friedrich Michael Landstorfer (1940–2025). Take a ¾ wave monopole, and bend it, so it is only just over ½ wavelength high.

The optimization doubles the gain or sensitivity of the antenna with respect to the straight ¾ wave element (from +6.35 dBi to +9.48 dBi), and concentrates the energy in a narrow pattern close to the horizon.

A side note… do you see how the energy flow streamlines swerve one way or the other as they converge in the interference maxima and diverge away from the interference minima? The “counterintuitive” paths of the pilot-wave interpretation are not so counterintuitive when you have trained your intuition on tracking electromagnetic energy flow.

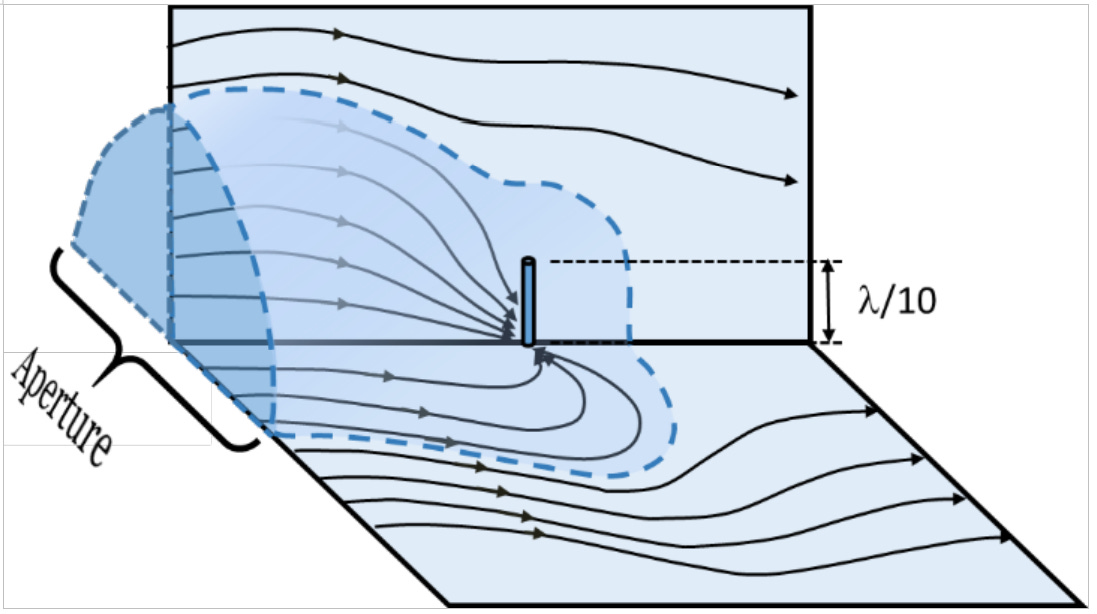

An efficient electrically-small antenna can couple to and capture field energy about a sixth of a wavelength (λ/2π) away. The superposition of the incident and reflected fields from the receive antenna serve to guide the energy in the surrounding space to be captured and received. The apparent aperture can be much larger than one might expect from the physical aperture of the antenna alone. For instance, here’s a short (tenth of a wavelength tall) monopole intercepting the energy-flow streamlines from a larger aperture. The diameter of that aperture is about a third of a wavelength (λ/π).

The story of how antennas work does not end here – they have much more to teach us. I will expand on results like these and many more in Fields & Energy Book III: How Electromagnetism and Quantum Mechanics Work.

Tying back to my understanding of the æther, these explanations of antenna behavior implicitly rely on the fact that energy is stored in free space and moves progressively.

What exactly is an ultrawideband antenna? Broadly speaking, what are their applications?

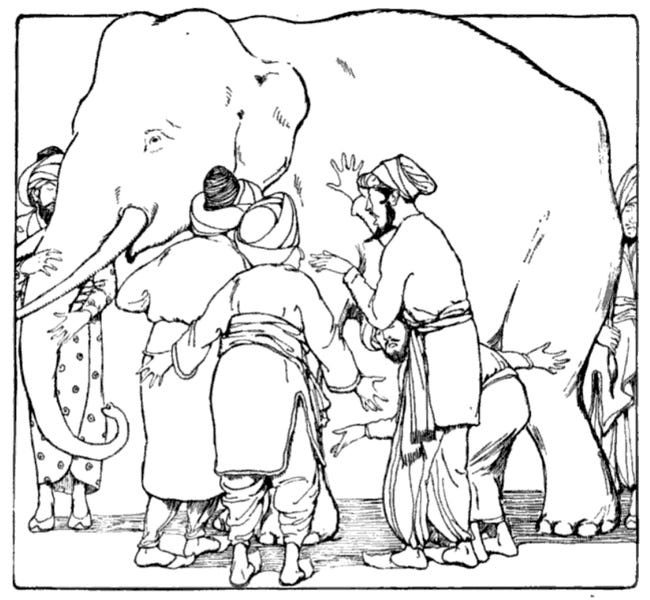

An ancient Indian parable tells the story of six blind men who come across an elephant. One, feeling the trunk, declares that the elephant is a snake. Another touches a leg and says that the elephant is a tree. The third feels the elephant’s side and thinks that the animal is a wall. The fourth encounters the tail and believes that the elephant is a rope. The fifth grabs an ear and says that the elephant is a fan. The sixth finds a tusk and concludes that the elephant is a spear. Each is correct. Each grasped a part of the truth, but only by pooling their various perspectives do the blind men achieve a complete understanding.

Antennas in general and ultrawideband (UWB) antennas in particular are like elephants.

A wireless system engineer designing an RF link treats an antenna as a transducer – a device that converts a signal from one form of energy to another. A few basic properties like gain, pattern, and matching are often all the system engineer really needs to know.

An antenna engineer optimizing matching considers an antenna as a transmission line extension: a structure that transitions from coupling guided waves to launching them into free space. Impedance control of the transmission line and transition to free space enhances the quality of the match.

An antenna designer seeking a particular pattern conceives of an antenna as a radiator: a locus of currents that give rise to fields that propagate away in a desired arrangement. An antenna designer employs the geometry of an antenna structure to couple to fields in a particular configuration.

An antenna scientist desiring enlightenment understands an antenna is an energy convertor: a device that transforms bound or reactive energy into propagating or radiation energy, and vice versa. An appreciation of how antennas work yields insights that make antennas better.

Truly understanding the elephant that is a UWB antenna requires assimilation of all these perspectives.

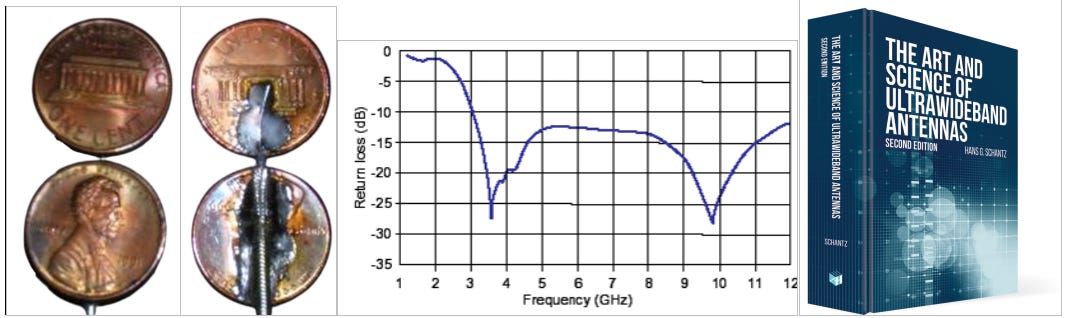

The FCC defines “ultrawideband” as possessing a bandwidth greater than 20% of the center bandwidth. For instance, an antenna operating at a frequency of 1 GHz would need a bandwidth greater than 200 MHz to be considered UWB. Typical UWB antennas, like those I designed, would operate from 3-10 GHz, or more than 100% fractional bandwidth.

The real challenge is designing an antenna that can be manufactured at low cost and integrated with a wireless device. I established that two cents was the price point to beat. I discuss the two-cent dipole and much more about ultrawideband antennas in my book, The Art and Science of Ultrawideband Antennas.

UWB antennas are used in applications that need very wide frequency ranges and fine time resolution, enabling precise localization, high-resolution sensing, and short-range high-data-rate communications. Key uses include short-range wireless links, personal and body area networks, ground-penetrating and medical imaging, automotive and drone collision avoidance, indoor positioning with centimeter accuracy, gesture recognition, and non-invasive health monitoring. They are also applied in military systems for surveillance, low-detectability communications, and high-resolution radar, as well as in industrial settings for non-destructive testing, smart factories, and logistics tracking.

In the DemystifySci interview you mentioned Boscovitch. Can you talk a bit more about him? The only other person I’ve seen mention him is clif high, who has indicated that he was an early Czech aether theorist who more or less had things figured out. I hadn’t realized that Faraday was drawing directly on his work, and there’s this sense that he’s this foundational but somehow marginalized figure in the history of science.

My friend,

, wrote a wonderful essay over at his Fiat Lux Substack on the Croatian Jesuit physicist Roger Boscovich (1711–1787) [Ruđer Josip Bošković] who lived in the Republic of Ragusa on the shores of the Adriatic.Boscovich interpreted the physics of Isaac Newton (1642–1727) in terms of point particles acting at a distance through a void. His was a model for matter comprising point particles that interact with each other at a distance through the intervening space. Newton rejected this notion saying in his 1693 letter to Richard Bentley:

That one body may act upon another at a distance through a vacuum, without the mediation of any thing else, by and through which their action and force may be conveyed from one to another, is to me so great an absurdity, that I believe no man, who has in philosophical matters a competent faculty of thinking, can ever fall into it.

James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879), famed discoverer of the laws of electromagnetism, noted in 1876 in his essay on action at a distance:

And when the Newtonian philosophy gained ground in Europe, it was the opinion of Cotes rather than that of Newton that became most prevalent, till at last Boscovich propounded his theory, that matter is a congeries of mathematical points, each endowed with the power of attracting or repelling others according to fixed laws. In his world, matter is unextended, and contact impossible. He did not forget, however, to endow his mathematical points with inertia.

In his 1844 paper “A speculation touching electric conduction and the nature of matter,” Michael Faraday (1791–1867) embraced Boscovich’s conception of atoms as “mere centres of forces or powers, not particles of matter, in which the powers themselves reside.” However, Faraday took this further than Boscovich had originally intended. Rather than applying Boscovich’s discrete point particles to create an aether, Faraday used Boscovich’s force-centered view to eliminate the need for a separate aether altogether. Faraday reified force and made it the material entity responsible for physical interactions. Faraday’s “lines of force” permeating all space became the medium through which electromagnetic phenomena propagated: a revolutionary idea that anticipated Maxwell’s field equations and modern field theory.

Faraday’s approach yielded a continuum throughout space in contraposition to Boscovich’s atoms and void model. And it was Faraday’s model that led William Thomson (1824–1908) (before he became Lord Kelvin) and later Maxwell to envision the supposedly empty space between charges and currents as a kind of medium capable of storing and conveying energy.

Philosophical Speculations

When you were asked about the implications of your work during the DemystifySci interview, and of taking the pilot wave interpretation of QM more seriously, it felt like you were really playing it safe. The applications you suggested were these rather specific theoretical problems which didn’t immediately suggest practical applications to me. So, setting conservatism aside, what could this unlock? Could research in this direction be what leads to electrogravitic flying saucers? Tesla towers? Death rays? Time travel? Put the scientist hat down, put the sci-fi writer hat on, and go wild.

The story is probably apocryphal, but when Faraday was asked about the value of his discovery of induction, he is supposed to have answered “Of what value is a newborn baby?” Faraday’s discovery ultimately became the basis of our modern electric civilization, enabling motors, generators, and electrical distribution networks. Faraday wisely chose to under-promise and over-deliver, and I’m absolutely going to play it safe and follow his example.

Many discoveries lie dormant for decades before finding application. It was decades between Mendel’s laws of heredity and genetics, or E = mc2 and the nuclear reactor or the atomic bomb. Sometimes an individual discovery isn’t enough to trigger a breakthrough. The computer revolution needed vacuum tubes, then transistors, plus Boolean algebra, plus information theory, plus materials science advances. None of these discoveries were sufficient alone, but they were explosive in combination.

The wisest approach to a new discovery is enthusiastic exploration combined with intellectual humility about outcomes. We should pursue promising discoveries vigorously while remembering that science’s greatest gift is often surprise.

At a philosophical level, a purely physical account of reality leaves something important out: consciousness. Now, I have the impression that you’re skeptical of QM interpretations that require, e.g., observer effects, as these are sort of smuggling a kind of mysticism into physics via the back door. A similar criticism has often been made of the Big Bang, that it’s a bit too close to creationism. I rather suspect that this explains the popularity of quantum woo: people don’t want to inhabit a purely mechanistic reality, they want some kind of magic to be there. Even physicists. So I’d be really interested in your views on where consciousness fits in with pilot wave theory.

In standard quantum mechanics, consciousness often gets entangled with the measurement problem: the idea that conscious observation somehow “collapses” the wave function. This has led to various consciousness-centric interpretations, from von Neumann’s observer-induced collapse to more exotic ideas about consciousness creating reality and “it from bit.”

Pilot wave theory sidesteps this entirely. In Bohm’s formulation, particles have definite positions and velocities at all times, guided by “pilot waves” derived from the wave function. There’s no wave function collapse and no special role for measurement or consciousness in the theory’s basic mechanics. Reality is deterministic and objective, regardless of observers.

“Pilot wave theory sidesteps this entirely.” Yes, but you also somewhat sidestepped the essence of the question: it’s clear that pilot wave theory is fully mechanistic, and doesn’t require consciousness at all. So wither consciousness? Is it simply an epiphenomenon? Is reality dualistic? Reality certainly seems to include consciousness as a phenomenon. For that matter so does physics: physics requires an observer, but what is an observer? What I’m curious about are your own thoughts on what consciousness is, how it fits into reality, or whether it’s real at all.

I’m a physicist, not a physician. Don’t expect me to define what consciousness is or how it works. We don’t fully understand quantum mechanics. Neither do we fully understand consciousness. I don’t think it’s very productive to try to explain one by appealing to the other. Certainly, consciousness and quantum mechanics are both real, and we have much to learn about both. I’ve been working hard to understand quantum mechanics. On consciousness, not so much. I’d rather not opine on something unless I have a well-thought-out and worthwhile opinion to share.

If I can summarize the discussion of the aether in the DemystifySci podcast, which was a bit elliptic as it extended across a number of different topics, your view seems to be essentially that the aether can be thought of as sort of the underlying field that encompasses all physical fields, for example electromagnetic fields, gravitational fields, relativistic space-time, while also including the vacuum (which comes with the quantum foam, vacuum energy, etc). It has all the properties that have been identified by modern science for those fields. Only, instead of mathematical fictions, you suggest that fields must be thought of as really existing, physical objects. That seems actually like such a small change from the way we already think, but at the same time it is also rather profound. It’s almost like, deprived of an aether, physics had to cobble an ad hoc aether together, one which dare not speak its name because, as we all know, the aether doesn’t exist. But as a result of that our aether theory is fragmentary and rather crippled, which in turn holds back fundamental physics and, almost certainly, technology. And probably also metaphysics and philosophy for that matter. Am I on the right track here? Please correct any misunderstandings I have.

You said it well, but I’d be a bit more abstract in my definition for æther. There exists a process or mechanism whereby electromagnetic energy is stored and conveyed in the free space within and around electromagnetic systems. We can call this “the æther,” without specifying any specific underlying process or mechanism. Æther is merely the conviction that actions require actors and that doing requires a doer. “Out of nothing, nothing comes,” declared the pre-Socratic philosopher Parmenides in the fifth century BC. We should heed his ancient wisdom.

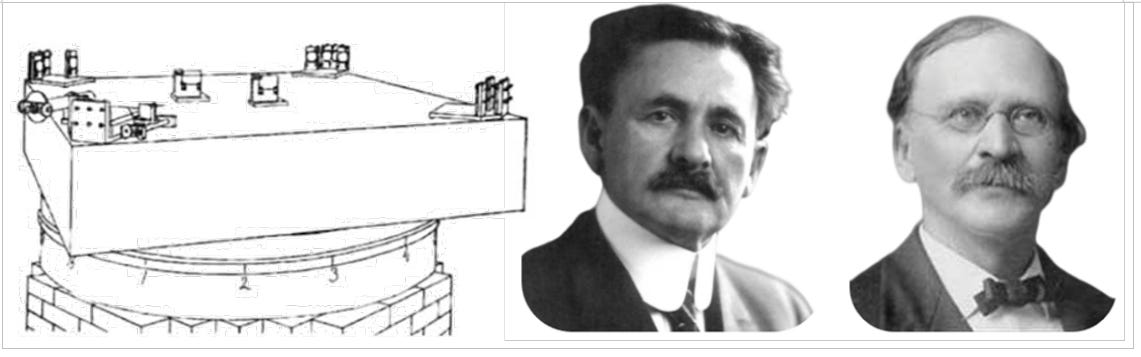

After Albert A. Michelson (1852–1931) and Edward W. Morley (1838–1923) failed to discover the interference fringe shifts they expected in 1887, people like Oliver Heaviside (1850–1925), George Francis FitzGerald (1851–1901), Joseph Larmor (1857–1942), and Hendrik Antoon Lorentz (1853–1928) worked to understand how that result might arise from the electrodynamics of moving bodies. Henri Poincaré (1854–1912) realized these results would require a new version of mechanics which he dubbed, “relativity,” where the speed of light would be the maximum velocity.

And then Albert Einstein (1879–1955) published his 1905 paper showing how Lorentz’s transforms followed from two principles: That the speed of light was constant for all observers, and that the laws of physics appeared the same for observers in all inertial frames. Einstein curiously did not cite any sources or references, but it is clear he was influenced by Poincaré and by an Austrian physicist, Ernst Mach (1838–1916).

Mach argued that observations were fundamental, and that scientific concepts were merely labels or tools we apply to organize our sense perceptions. For instance, Mach famously did not believe atoms were real (ironically, neither did he accept relativity). His acolyte, Einstein, took Mach’s teaching to heart, however, and figured out that relativity could be explained from two simple principles derived from what the observer actually sees: first that the speed of light would appear constant and second that the laws of physics would be the same.

How deeply Einstein was philosophically committed to Mach’s observer-centric approach is debatable, since in 1905 Einstein also published a paper on Brownian motion that went a long way toward establishing the reality of atoms. Einstein’s demonstration that relativity follows deductively from a couple of observer-centric principles led many physicists including Einstein himself to argue that the notion of an æther was superfluous – no process, no mechanism was necessary to explain electromagnetism. Focus on what the observer sees, everything just “happens,” relativity allows you to deductively work out the mathematical equations to describe it, and no metaphysical appeals to an æther are necessary to motivate or explain the result.

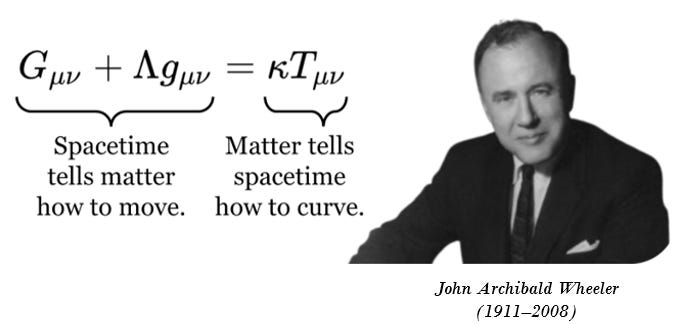

Einstein’s anti- æther absolutism began to dissolve when he came up with general relativity in 1915. General relativity explains how matter and energy tell spacetime how to curve and how spacetime tells matter how to move, in the formulation of John A. Wheeler (1911–2008). That curvature of spacetime smacks of ascribing physical properties to empty space – exactly the kind of thing that motivated Einstein’s predecessors to appeal to an æther.

In 1920, Einstein explicitly acknowledged that the curvature of space in General Relativity was a kind of æther, in a lecture at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands. That was the home turf of Lorentz, whose work Einstein deeply admired, and Lorentz had never abandoned the notion of an electromagnetic æther. “Space without æther is unthinkable,” Einstein now declared. Whether Einstein was merely offering an olive branch to his respected predecessor or undergoing a change of heart isn’t clear. Five years later, though, Einstein would be backed into a corner and forced to pick sides in the underlying philosophical debate.

In 1925, a young Werner Heisenberg (1901–1925) came to Berlin to deliver a lecture on quantum mechanics, and Einstein invited his young colleague back to his apartment to discuss Heisenberg’s new quantum theory. Heisenberg shared the story of this amazing meeting story only in 1970, long after Einstein’s death.

According to Heisenberg, Einstein asked, “What path are the electrons taking in your model?” And Heisenberg proudly told him there were no electron paths in his model. Heisenberg focused specifically on the observations, on what we observe before the process and what we observe after the process. What happens in between? That wasn’t part of Heisenberg’s theory at all.

Einstein objected that the electron has to be somewhere.

Heisenberg proceeded to quote Einstein back at Einstein and go through a lot of Einstein’s work on relativity to point out, that’s exactly the attitude that Einstein himself had: that we should focus on the observations, that we should not entertain these idle metaphysical speculations about what really goes on in between. So quantum theory, Heisenberg argued, follows in Einstein’s footsteps in presenting an observables-first theory of how the quantum world works. According to Heisenberg, Einstein was taken aback by that and said, “Well, perhaps I did use such a philosophy earlier and also wrote it, but it’s all nonsense, just the same.”

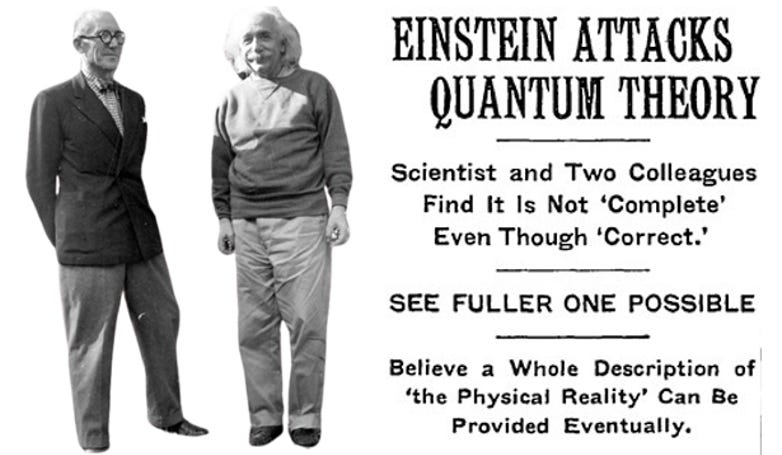

Einstein was convinced that quantum mechanics was incomplete and required the kind of hidden variables that Heisenberg rejected. Collaborating with Boris Yakovlevich Podolsky (1896–1966) and Nathan Rosen (1909–1995), Einstein wrote the “EPR paper,” advancing this view. In the long run, this paper may prove to be his most significant contribution to physics.

It is a small but profound shift in thinking: a commitment to there being an underlying process or mechanism, understanding what’s going on and extrapolating from there to make new discoveries. I developed my understanding of the æther merely by taking seriously the concept that energy is stored and conveyed in free space. I discovered that fields guide energy, but unlike the conventional picture, fields and energy behave differently, follow different rules of propagation. I used this physical picture to design ultrawideband antennas, to develop the laws of propagation for near-field signals, and to model how electrically small antennas work. I realized that my classical electromagnetic picture of fields guiding energy extrapolated to something very much like the pilot wave theory in quantum mechanics. So lately, I’ve been working on how to extrapolate what I’ve learned about electromagnetism down to the quantum realm.

For something that is supposed to be “nothing,” the vacuum is astonishingly full: it has a permittivity and permeability that set the speed of light and the impedance of space; it stores electric and magnetic energy and moves it from point to point; it teems with zero-point fluctuations that polarize charges, shift atomic spectra, and press conducting plates together in the Casimir effect; under strong fields it can shimmer with birefringence or even spawn particle-antiparticle pairs; in quantum chromodynamics it harbors condensates and topological structures; in relativity it carries an energy density that drives cosmic expansion and gives rise to phenomena like Hawking and Unruh radiation; and through the Higgs field it endows particles with mass. The “vacuum” is less a void than the dynamic stage on which all physics plays out, and some physicists’ insistence that there is no æther has made it more difficult to appreciate how it all works.

Among your many critiques of contemporary physics is that it is too deductive. To clarify for readers, deduction is when you reason from axioms or postulates to a conclusion. Induction moves in the opposite direction, attempting to reason about what the axioms or postulates should be based on empirical evidence. Plato thinks deductively, reasoning his way towards the Republic by cogitating about the Good, whereas Aristotle is inductive, collecting hundreds of constitutions and examining their political consequences as his way of arriving at general conclusions about politics. There’s also abduction, where a range of hypotheses are tested against the data in order to identify the best hypothesis. I think it’s really abduction that gets used the most these days in practice, for instance when a family of models is tested against a body of data in order to constrain the range of model parameters to within a range of uncertainty. In a sense almost all of the theories we work with now are unfalsifiable, because each model is really an uncountable infinity of models corresponding to all of the different parameters that can be inserted, and no matter how precise our observations become there’s always a subset of those parameters that can fit the data (and in extremis, new parameters can be added to the model). It strikes me that this deductive-abductive turn in modern physics is probably related to the general stagnation in the field. At the risk of getting you in trouble, I think you can also see this tendency in the social sciences, e.g. the ‘gender spectrum’ providing an infinite number of made-up gender identities which serve as models that can be ‘tested’ against individual psychological makeups, such that everyone can have a bespoke gender identity and the gender theory arrived at via deductive reasoning on the basis of axioms related to radical equality is endlessly verified. Of course, application of inductive reasoning - all multicellular organisms more or less having either sessile or mobile gametes, therefore there are only two sexes - brings the whole gender theory house of cards crashing down. I’m sure readers can think of other examples. So, returning to science - not necessarily physics - can you point to other examples of open problems which collapse simply by applying inductive methods?

Such examples are easier to see in hindsight.

Chemists had discovered dozens of elements, but their properties seemed chaotic. In 1869, Dmitri Mendeleev (1834–1907) arranged elements in order of atomic weight and noticed repeating patterns in valence and chemical behavior. He predicted missing elements (like gallium, scandium, germanium) and corrected atomic weights. The table was later explained theoretically by quantum mechanics, but the inductive discovery itself provided a unifying framework.

Planetary motions were well-measured but badly understood. Theories of Ptolemy (c. 100–170) and Copernicus (1473–1543) relied on circles and epicycles. Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) mined Tycho Brahe’s (1546–1601) precise data, discovering empirical laws: elliptical orbits, equal areas in equal times, and harmonic relation of orbital periods. Newton (1642–1727) later provided the theoretical grounding, but Kepler’s inductive leap collapsed centuries of confusion into three simple rules.

Inductive methods are helpful when we have a large body of data that doesn’t appear to make sense. We study the data, we identify common factors, we induce more general principles, and we verify them against the data set.

Looking forward, there are several problems ripe for solving. The first that comes to mind is the problem of “Dark Matter” and “Dark Energy.” To my mind, that’s a complete misnomer. To call it the problem of “Dark Matter” or “Dark Energy” is to presume a particular solution to the problem that the wide-scale motion and behavior of galaxies does not align with our understanding of gravity and the mass distributions involved. Michael McCulloch identifies 54 such anomalies in his very readable book, Quantised Accelerations: From Anomalies to New Physics, and he offers a plausible explanation. I discuss it here.

In the DemystifySci podcast, I found the discussion about the atom as an antenna to be quite a fascinating image. This would be a very specific kind of antenna of course: unidirectional as both transmitter and receiver, tuned to very specific energies, and one whose properties change depending on its energy level, e.g. it can only absorb one photon of a given wavelength, after which that energy level is filled and it’s now tuned to an entirely different set of energies. What I like about this image the most is that it casts atoms as elementary information transmitting, receiving and processing structures, which seems consistent thematically with eg Wheeler’s ‘it from bit’ approach to deriving the origin of fundamental physical laws. I guess this isn’t so much a question as an invitation to expound on this model, or metaphor, for the atom. What role are protons, neutrons, electrons, and photons playing here? What about the internal structure of protons?

The application of antenna theory to atomic physics is a topic I hope to address in the third volume of Fields & Energy. Discussing my speculations on how those ideas might play out is premature.

There are some interesting discoveries in modern physics that speak to the origins of physical laws. Emmy Noether (1882–1935) discovered that whenever the laws of physics have a continuous symmetry, there is an associated conserved quantity (Noether’s theorem). If the Lagrangian description of a system does not change when time is shifted, energy is conserved; if it does not change when space is shifted, momentum is conserved; and if it does not change when space is rotated, angular momentum is conserved. In this way, conservation laws are not arbitrary add-ons to mechanics but flow directly from the symmetries of nature, giving a deep unifying principle that underlies all of modern physics.

As always, thank you to everyone who devoted their attention to reading this all the way through to the end, and my immense gratitude to those of you who support my writing. I hope you found this discussion as interesting as I did.

Dr. Schantz is currently “seeking opportunities.” If you have a tricky electromagnetic problem, if no one else can solve it, and if you want someone to take a fresh and novel approach to your problem, maybe you can hire Dr. Schantz.

You can follow Dr. Schantz at his Fields & Energy Substack:

Fields & Energy Book I: Fundamentals & Origins of Electromagnetism will be released on Amazon the first week of December.

About 25 years ago I studied electrical engineering at university. I'd played with electricity, electronics, amateur radio for a long time as a child and thought I had a reasonable understanding of SOME things. Did pretty well - even Diff Eqs.

Then came Electromagnetic Fields I and II. Jesus H. Roosevelt Christ - I aced both semesters, could do the math, but I don't understand the essence of fields any better now on a fundamental level than I did when I started.

You might interview Gerald Pollack. His newest book is Charged : The Unexpected Role of Electricity in the Workings of Nature, the previous was The Four Phases of Water.

Required reading to understand how the world works. He faces the same challenges described by Hans in getting it accepted, even though he is a Prof Bioengineering at https://bioe.uw.edu/portfolio-items/pollack/