I’m always on the lookout for interesting new science-fiction novels. Reading is one of my favourite ways of procrastinating when I’m supposed to be writing. Unfortunately, finding those novels is tricky. The shelves of the bookstores are flooded with the tasteless porridge slopped out by the politicized editorial staff of the big publishers. This has naturally produced a counter-reaction in indie publishing, but that comes with its own problems. Don’t want to read about racialized pronoun people in space? Well, here’s an eight-volume saga about Sgt. Slaughter and the Powered Armour Mercenaries, whose thinly veiled GWOT-in-Space narrative is liberally peppered with little asides that own the libs! You can have well-edited culture war propaganda that’s passed through the sensitivity readers, or you can have culture war propaganda from the other side, without sensitivity readers, or editing.

But sometimes you just want to read something that isn’t political, which isn’t trying to send a message, but which just tells a good story.

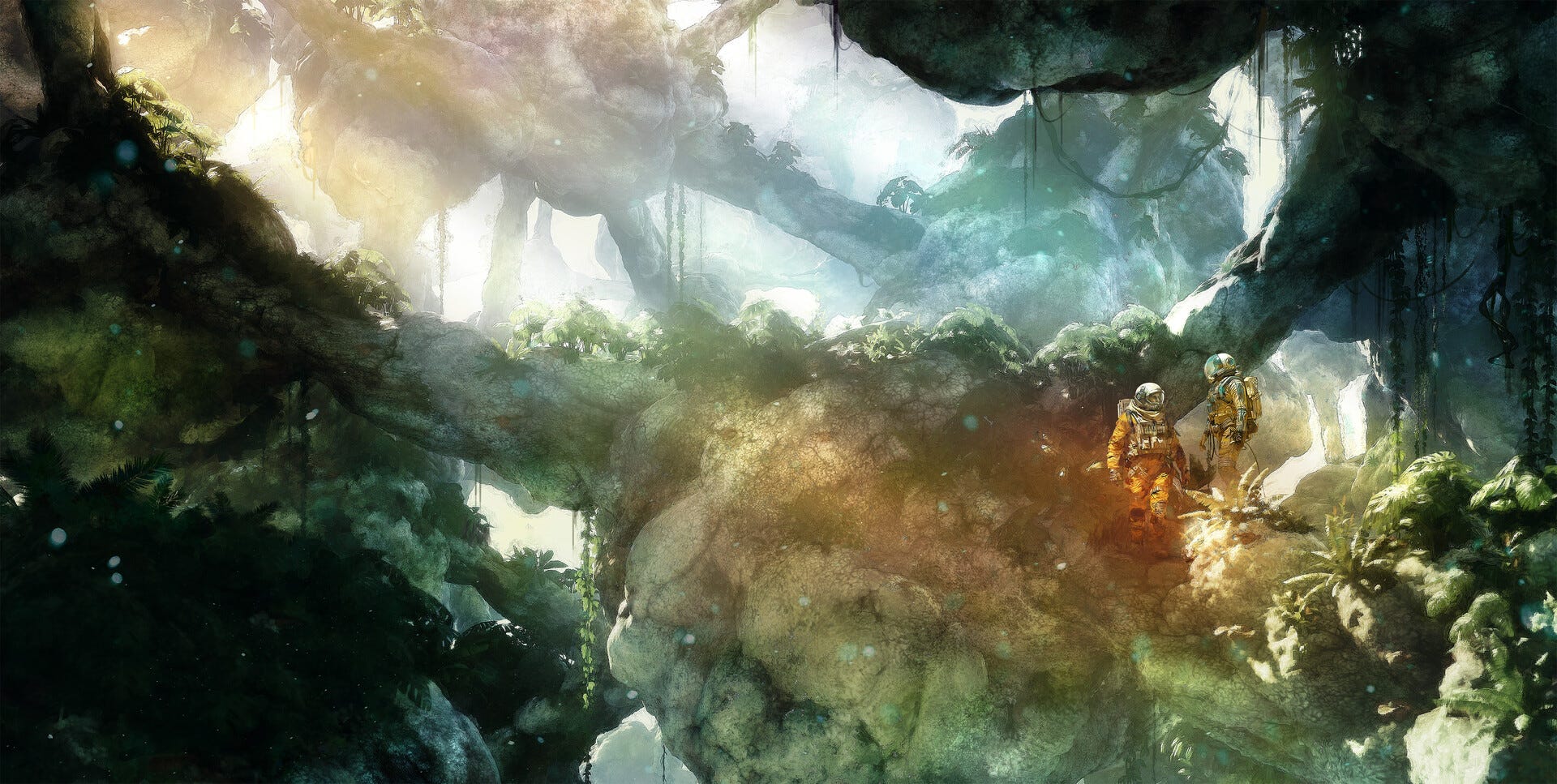

’s debut offering Pallas is such a novel. It isn’t politically correct, but it isn’t bending over backwards to be politically incorrect, either. Contemporary culture war politics are simply irrelevant here, and so, blessedly, that is the last time that politics will be mentioned.For Kylan Bence, hauling freight through the Belt is lonely work, and when his ship malfunctions that loneliness might kill him. Stranded on the asteroid Pallas, in view of a concrete dome long thought abandoned, he chances a distress signal—and gets a response.

As he enters the settlement, a secret paradise greets him. Lush and vibrant plants, real food, clean water—and a population desperate to keep him inside . . . with everything else they've kept hidden in the soil, the air, and under the skin.

The vibe of Pallas is sort of hybridization of the original Alien, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 19th century Gothic story Rappaccini’s Daughter, and the Odyssey’s lotus eaters, with a generous side helping of creeping body horror. That last is no joke: do not do what I did, and eat lunch while reading this, because you may lose it.

The story takes place almost entirely inside its namesake asteroid. While the year in unspecified, it seems to be about two hundred years from now. The solar system is largely explored and settled, at least to such an extent that the industrial combines that seem to be the primary governance bodies can lose track of whole colonies for over a century. The world-building mostly takes place off-screen; there’s almost no exposition, with none of the jargon-laden info-dump techno-babble that tends to plague sci-fi. The reader knows only as much as the viewpoint characters know, which isn’t a whole lot. The protagonist, Kylan Bence, is a dyslexic working-class space trucker with anger management problems who’s just trying to get by. The other characters are natives of the settlement, who have been kept in a state of carefully cultivated ignorance by the its rulers.

Kuznak’s prose is sensorily vivid. Her sentences tend to be terse, throwing the viewpoint character’s emotions, thoughts, impressions, and observations at the reader like little rabbit punches. The overall effect is to immerse the reader in a character’s mind, such that you simultaneously see what they see, smell what they smell, taste what they taste, and feel what they feel. It all arrives jumbled up, just like actual sense data does. This gives her writing a sort of manic immediacy that grabs you by the scruff of the neck and frog marches you through the story.

Kuznak is a bit stylistically experimental. The voice switches between first and third person as the perspective moves from one character to the next, giving the sense of floating around, alternately watching the characters and slipping inside their heads. This could have become confusing with a less skilful writer, but Kuznak pulls it off – at no point did I feel like I was losing track of whose eyes I was seeing through. This is especially impressive given that psychological disorientation is a running theme: Kylan spends much of novel intoxicated or feverish, and Kuznak manages to put you inside his head, his heart, and his gut. It’s dizzying without being bewildering. While the characters are almost invariably confused, the reader isn’t: the plot is straightforward and entirely logical, while the motivations of the characters are perfectly understandable, and their behaviour perfectly sensible given their personalities, skills, knowledge, fears, and desires.

Speaking of desires, sex plays a role in the narrative, and a rather central one. Indeed, the tender core of the plot is a love story which threads through the encompassing sci-fi/horror narrative. Despite this, the sex is never tasteless or pornographic: Pallas would probably get an R-rating if brought to the silver screen (and, honestly, it should be), but certainly not an X-rating. Sex is mentioned more than portrayed, and I wish more authors did this because portrayals of sex usually feel awkward rather than titillating. You could give this to a teenager with a clear conscience.

The characters are flawed and very human, but they never feel unsympathetic or frustrating. To the contrary, they are trying to solve the problems facing them as well as they can, given their capabilities and level of understanding. They are competent, without being omnipotent. They don’t wallow in their flaws, but struggle with them and, to a certain degree, even overcome them. Their character arcs are as much about confronting their inner demons as they are about finding solutions to external problems.

Stylistically experimental, psychologically driven science fiction can often feel a bit ‘soft’ due to vaguely described science magic, unintentional howlers where the author violates known physics without even realizing it, or inconsistencies between stated technological capabilities and the story’s action in which the author doesn’t quite think implications through. Pallas, thankfully, didn’t give my autism cause to complain. Mostly this is because there isn’t much magic tech: the technology all feels like fairly straightforward extrapolations of current capabilities. The ecology of the settlement, the limitations it imposes on the lives of its inhabitants, and the secondary effects of this on the settlement’s culture, all felt fleshed out, realistic, and internally consistent. When the characters start to penetrate the mysteries of the settlement’s origins, the scientific underpinnings come off as quite plausible. Those underpinnings are also original enough to be interesting; in the interests of avoiding spoilers, that’s all I’ll say about them, aside from this: Pallas manages to feel like supernatural horror, while remaining entirely within the boundaries of believable scientific reality.

Some aspects did have me wondering, such as the choice of Pallas for the settlement. Pallas is thought to be a carbonaceous chondrite, and therefore a poor prospect for asteroid mining, which I would think would focus on nickel-iron asteroids, so it was a bit odd that it would be picked for a mining settlement; then again, the mines were closed, so. It was also a bit surprising that the settlement was entirely lost: Pallas is the third-largest body in the Belt, and I have a hard time imagining that a large, lavishly funded settlement could be essentially forgotten about for a century and a half. Admittedly, space travel in this setting is explicitly slow: Bence is stranded there for an extended time as he waits for a rescue ship to pick him up, which the plot uses to good atmospheric effect. There’s also some indication that the colony wasn’t so much lost as ‘lost’, i.e. covered up by the Company for its own reasons, much as the corporation in Alien ‘forgot’ LV-426. It’s never stated explicitly, but I couldn’t help but wonder if Bence getting stranded there wasn’t entirely accidental.

Those are quibbles, however, which never took me out of this fun, fast, well-written, and unsettling read. You can pick it up from Amazon in either e-book or paperback here. If you give it a read (and you should), let us know what you think in the comments.

"something that isn't trying to send a message but just to tell a good story" is what I want, not just sometimes but ALWAYS. Never want the other kind.

Written with intriguing details about this novel, enough to give prospective readers impetus. Thank you @John Carter