The Imago DEI

Do You Think You’re Better Than Me?

A Précis, Because This Turned Out To Be Really Long

The idea of the ‘equality of man’ has been deeply influential in Western thought, leading to the universal dignity of man, the natural rights of man, universal human rights, anti-discrimination laws, civil rights, equality under the law, the manumission of slaves and global suppression of slavery, the emancipation of women, universal suffrage, racial equality, sexual equality, gay rights, and most recently the concept of ‘equity’ as enshrined in the ‘Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity’ programs that have permeated Western institutions. Equality has for so long been understood as an absolute good, both an underlying spiritual reality of the human condition and, somewhat paradoxically, an ideal for society to strive towards, that the assumption that equality is both real and positive goes largely unquestioned, including by many of those who oppose the idea’s deleterious practical consequences.

The numerous and destructive excesses of equality in recent years have frequently led conservatives and classical liberals to argue for ‘equality of opportunity, not equality of outcome’, on the grounds that left-wing champions of DEI have misunderstood and are misapplying the concept of equality. This strategy has been generally ineffective, as ‘equality of opportunity’ becomes absurd given the natural variance in ability between human individuals and groups. Others have argued that widespread acceptance of that natural variance will force the champions of equality to abandon the worst excesses. This is also mistaken, because it misses both the fundamentally theological nature of the belief and the motivated reasoning that underpins it, a combination which is immune to empirical arguments.

Here, I argue that equality is a pure abstraction which does not actually exist in the phenomenal world, including in the most fundamental sense of the moral or spiritual equality of man derived from the concept of the ‘Imago Dei’ or ‘the image of God’, which is the ultimate theological origin from which all subsequent notions of equality have been derived, and which I attempt to demonstrate is itself conceptually incoherent given that some humans fail to display the properties associated with the Imago Dei, while some animals do. I further argue that the popular belief in ‘equality under the law’ is also dangerously mistaken if it is taken to mean a ‘one size fits all’ law, as – given the influence of the idea of equality – this then leads to law that fails to account for the biological variety of human types, thereby contributing to societal decay. Finally, I argue that, for individuals, society, and the human species to follow an upwards developmental trajectory, an embrace of inequality is absolutely necessary.

As you might expect this précis leaves out a fair number of side quests. It’s the journey, not the destination.

The Debate of the Millennium

Recently Passage Press was somehow able to get Harvard professor Danielle Allen to agree to debate Neoreactionary blogger Curtis Yarvin, at Harvard no less, on the broad subjects of equality and democracy. Being a Harvard professor – and one of 25 “University professors” at that, apparently considered Harvard’s highest honour – Allen is of course a committed partisan of both democracy and equality. Yarvin famously champions the antipodal position, believing that equality is an absurd superstition, democracy a folly, and some form of constitutional techno-monarchy to be far preferable to the ochlocracy of the lowest common denominator. The debate itself was nothing special – though it does mark an interesting cultural shift, signalling that the liberal establishment is now finding it necessary to engage with its ideological opposition on the dissident right, rather than simply ignoring or silencing it – but the subject has been the defining question of the last two thousand years.

The debate was about equality, but demonstrated the opposite. On the one hand, the establishment: tenured, titled, privileged, elevated to her station on the basis of her advocacy for the egalitarian ideals the establishment professes to hold (and no doubt also in large part due to her intersectionally oppressed identities, the elevation of which to her station symbolizes that egalitarianism). On the other hand, an outlaw philosopher, who for the first several years of his literary career published not under his own name in academic journals, but on a blog under a pseudonym, to shelter from the social and economic sanctions that were the only material reward he could expect for his heretical musings. One of them richly rewarded for saying things pleasing to power, the other one step above the life of a fugitive for saying true things about power. One of them speaking in turgid buzzwords and tired bromides, the other dancing lightly from historical analogies to political theory to funny metaphors. One of them insisting that there was no contradiction between a commitment to pluralism and a commitment to truth, the other holding that there could be no pluralistic relationship between veritas and its absence. One of them, at the end, was even gracious – offering to make the case for the other’s position (that Harvard remains a potentially valuable institution and should therefore not be firebombed) as well possible; the other extended no such collegial courtesy, but finished on the same condescending note that she’d struck throughout.

Perhaps the most striking difference between the two was the tone. Yarvin was characteristically irreverent and playful, approaching the questions as a fun game with the objective of getting a bit closer to truth, and hopefully amusing and entertaining the audience along the way. Allen by contrast was patronizing: she wasn’t educating the audience, she was chastising them; she wasn’t engaging in a good faith adversarial contest with her interlocutor, but rather scolding him for being a very naughty boy. Listening to Yarvin was like having a beer with an interesting friend down at the pub. Enduring Allen was like being nagged by your sister-in-law.

This is what Harvard has come to; this is what the storied institution elevates to the celebrated ranks of its most elect scholars.

Thus are the wages of our embrace of equality.

About halfway through the debate Allen points out that ‘equality’ can and does take on a range of different meanings: moral, political, social, intellectual, economic, and so on. She insists that it’s necessary for critics of equality to clarify what exactly it is that they mean by the word before their arguments can be taken seriously, and gives the impression that the kind of equality she defends is moral equality: that is, the idea that all human beings are of equivalent moral worth, by virtue of being human and in that sense the same.

Yarvin responded by wondering whether ‘human’ status is a Boolean quality, a binary yes/no, pointing out that we wouldn’t consider a chimpanzee human despite its genetic similarity, but that in between Pan troglodytes and Homo sapiens is a whole family of missing links from Australopithecus afarensis to Homo naledi to Homo erectus, where the question of ‘which is human’ becomes extremely murky.

There may have been a Straussian subtext to Yarvin’s point about missing links, an indirect implication that either zipped over Allen’s head or which, more charitably, she refused to dignify with an acknowledgement: was Yarvin’s debate partner, herself, one of those missing links?

During his opening remarks Yarvin made another observation whose actual meaning was also, I think, found in the empty spaces between his words. To prepare for the debate, he read Allen’s book – with the captivatingly generic title Justice By Means of Democracy – and remarked that its repetitive, ritualistic recitations of faith in the revealed truth of the creed of egalitarian democracy read like an Islamic history written by a Muslim. The implication cuts to the heart of the question of equality: when all the verbiage of centuries of accumulated political theory and moral philosophy is peeled away, ‘equality’ is in its origin a fundamentally theological proposition.

Moral equality, or what Christians would call spiritual equality, is at the foundation of every other kind of equality. It’s the philosophical backstop that makes political equality, economic equality, social equality, and so on appear as desirable goals in the first place.

Spiritual equality is the proposition that all human beings have souls of infinite and equal worth, because we are all imprinted with the Imago Dei, the ‘image of God’. This has its origins in Genesis: ‘God made man in His own image’. In the Almighty’s eyes there is no difference at all between a beggar and a king, a man and a woman, a mother and a murderer. There is neither Jew nor Greek, etc.

This was a revolutionary idea when it was first articulated. The pre-Christian pagans found the concept of spiritual equality facially absurd. They pragmatically assumed that some souls – those of heroes, sages, lawgivers – were closer to the divine than others, such as tyrants, perverts, criminals, and traitors (who were as far away from the divine as it was humanly possible to be), or even the ordinary and unremarkable men, neither particularly good nor especially bad, whose fate in the afterlife was to fade into forgotten obscurity amongst the featureless grey shades of Hades.

The doctrine of moral quality sounds very nice, but it leads to perverse conclusions.

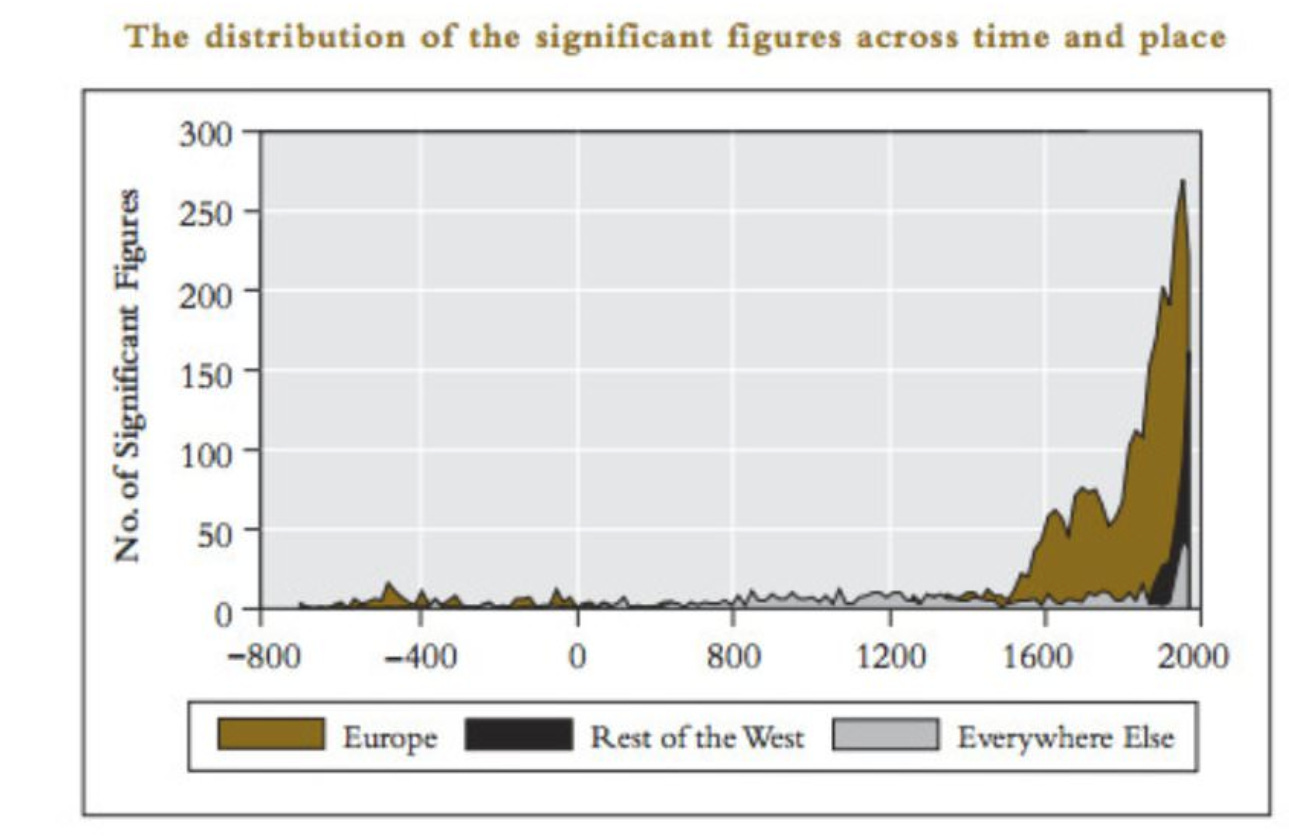

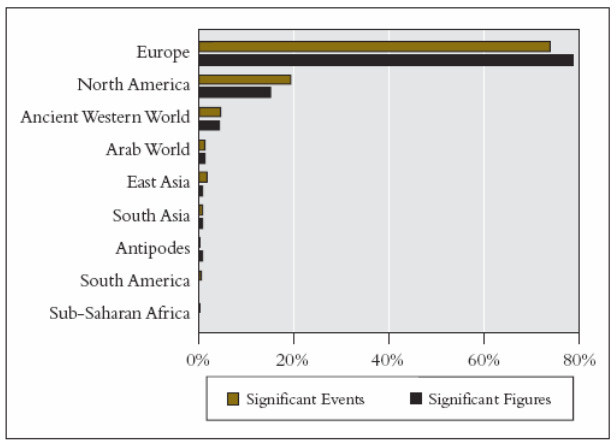

Consider the results quantified by Charles Murray in his book Human Accomplishment. Virtually every advance in philosophy, science, technology, and the arts, throughout the entirety of human history, has been achieved either in Europe or in North America, i.e. it has overwhelmingly been achieved by white people. These achievements have not only benefited Europeans, but have raised the standard of living of the entire human species to heights undreamed of even a few centuries before.

Human achievement was not homogeneously distributed either in time or in space, even within Europe. The vast majority occurred in the last few hundred years, and the vast majority of that has emerged from a narrowly circumscribed part of Western Europe, roughly Italy, Germany, Scandinavia, and England.

Now, let us suppose that orbital nuclear bombardment scoured this small polygon of the globe clean of life on New Year’s Eve of the year of our Lord 1300. The explosion in scientific and technological knowledge of the next several centuries would almost certainly have been stillborn. Humanity would have remained in the iron age. This would have been a monstrous crime, not only due to the immediate loss of life, but due to the shadow cast by a species-level lobotomy that deprived humanity of all of the advantages those advancements would bring.

What if a comparably sized region – with a similar population size – was targeted instead, say in sub-Saharan Africa? Certainly this would still be a great crime due to the loss of life. But would it be as great a crime? Were those lives as valuable to the human species as the lives in Europe, given the vastly greater contributions to human flourishing that were to be made by Europeans, as compared to the negligible, indeed for all practical purposes non-existent, contributions made by Africans? Even what few contributions Africans have made, have almost entirely been made by Africans under the tutelage of Europeans in the New World: without Europe, there would be no American colonization, thus no Atlantic slave trade, and therefore no jazz, blues, rock’n’roll, hip-hop, or Thomas Sowell.

Even to ask this question sounds bestial, doesn’t it? You feel vaguely unclean just thinking about it. But make no mistake: moral equality demands that the life of Ngubu the professional witch doctor and part-time rape enthusiast is every bit as worthy as that of Newton the mathematical physicist and amateur alchemist. Moral equality does not permit you to weigh the value of human life with a utilitarian, consequentialist scale. But queasy as it might make you feel to contemplate the question of whether Newton’s life is more valuable than Ngubu’s in some absolute sense, you also know full well which of the two regions the champions of equality would target, if they had to make a choice. And they would do so without blinking.

The History of Equality

Throughout almost the entirety of the Christian era moral equality was considered a fundamentally religious question. Theologians went to great exegetical lengths to reaffirm that in the temporal realm, political and social hierarchy was right and good – that the equality of the beggar and the king, the knave and the knight, pertained only beyond the gates of Heaven. Here on Earth the political order reflected the divine order, with the king as the stand-in for God; since hierarchies had been ordained by God as a part of His creation, then so long as they remained oriented towards God, they were righteous and just.

The doctrine of human moral equality wasn’t really a bad thing through this period. It helped to moderate the worst excesses of political and social hierarchies, encouraging milder forms of government that preferred fairness to oppression. Christian apologists would certainly point out that the stunning advances Charles Murray catalogued in Human Accomplishment were all made by Christian Europeans, and that the Church played a considerable role in fostering the environment in which this explosive intellectual ferment could occur.

Ideas have consequences, however, and eventually, probably inevitably, the logical consequences of equality broke free of the theological cage. Exegesis could hold back the tide for only so long. Locke came along to proclaim the universal rights of man to life, liberty, and property on the grounds that all men are created by God as rational and therefore equal beings, and from this challenged the authority of the monarchy, for the king was after all a man like any other, neither better nor worse. The liberal rebels of the American revolution borrowed directly from Locke when they wrote in the Declaration of Independence that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” where they substituted ‘pursuit of happiness’ for ‘property’ because it sounded less greedy and therefore nicer.

The American founders did not, of course, believe that all men are literally equal in the sense that they are the same in every respect, any more than Locke, or Augustine, or anyone else did. The political equality they sought was that of a level playing field, in which basic rules – freedom of speech, conscience, arms, property, privacy, and so on – were respected. These were really just the same set of rights that Anglo-Saxon yeomen had been accustomed to claiming for themselves since the fifth century. When their blood had purchased America’s independence, America’s founders naturally restricted the franchise of the new republic to land-owning white men, a small minority of the population, which struck everyone at the time as simple and obvious good sense. Why would you let irresponsible people, men that had not proven themselves, men or low or at any rate untested ability, participate in the political process? Much less women or negroes?

Granting universal suffrage to every warm body struck America’s Founders as a sure gateway to universal suffering. They still possessed the aristocratic instinct for distinction, an implicit understanding that there were natural hierarchies. When they insisted that ‘all men are created equal’, they certainly did not mean ‘all’ men, but men like themselves. The subtext of the Declaration of Independence was that the natural hierarchy was unbalanced – that America’s nascent aristocracy was the peer of the British aristocracy, which was keeping them from taking their rightful place as the self-governing nobility of the New World. But they did not invoke this natural order, and instead cloaked their motivations in the democratic rhetoric of equality. That is not to say that they did not believe some of this rhetoric themselves: there were debates among them about the consistency between slavery and equality, for example, and Washington famously refused to accept a crown.

Later generations took the Founders at their literal meaning: ‘all men’ means all men. The logic of their fine words caught up to the republican order they established. Step by step the franchise was extended: first to all white men; then to black men; finally to women. In 1971 the voting age was reduced from 21 to 18, and the Democrats perennially bring back the suggestion that it should be lowered still further, to 16. It’s hard to see why it should stop there: why not let ten-year-olds vote? Or toddlers? Ageism is just another kind of bigotry, you know.

Just as ‘all men’ came to be interpreted as all men rather than ‘all men (like us)’, so ‘created equal’ has come to be understood in the most literal fashion. The political equality of ‘equal rights’ that was built on the moral equality of the Imago Dei evolved into the flattening dogma of total equality which holds that there are no meaningful differences whatsoever between human beings.

We have not quite gotten to the point at which equalists will insist that there are no individual differences: for now, they limit themselves to the lesser mental illness, that there are no group differences. A Somali and a Swede are functionally identical in all respects, so Sweden (and Minnesota) must suffer a surfeit of Somalis. There’s no functional difference between a male and a female, so the Special Forces must meet female recruitment and retention quotas. And so on and so forth.

The origins of moral equality are theological, but the secular ethicists and philosophers who champion it do not couch their arguments in appeals to scripture. However, many borrow the subsidiary arguments, for example regarding universal rationality, which theologians advanced in centuries past, albeit with the religious serial numbers filed off. Locke and Kant both did this.

Others simply take moral equality as an axiom and reason from there. Rousseau’s social contract and Marx’s communism both had the moral equality of man in the background as an unquestioned assumption.

Other philosophers engage in ex post facto reasoning: the society created by the moral equality that emerged from Christian theology is clearly a good society, therefore moral equality is clearly a good thing. John Stuart Mill defended moral equality on the grounds that more equal societies have better outcomes in the sense that they produce the most happiness for the largest number of people, and recommended the emancipation of women on these grounds. Contemporary thinkers such as Amyarta Sen, Thomas Picketty, and Elizabeth Anderson also start from this sociological position, observing that equal societies are better societies because they enjoy lower crime, higher rates of social trust, and so on; moral equality is then derived, by unspoken implication. Thus, while equality in the strict sense that we are all the same may be fictitious in practice, it is usefully fictitious. It keeps us from being beastly to one another; it motivates charity towards the less fortunate; it encourages the strong to protect the weak, instead of ruthlessly exploiting them; it justifies the level playing field upon which meritocratic systems are erected; it leads to a fair distribution of resources.

The influential ‘veil of ignorance’ developed by John Rawls, in which we are asked to imagine what kind of society we would prefer if we did not know to which family and in which circumstances we should be born, is a kind of a hybrid of the theological and sociological arguments. Rawls argues that from the perspective of disembodied souls fated to be randomly slotted into bodies anywhere on Earth, belonging to any country, race, or social class, we should obviously prefer a society that is more equal, rather than less, else we should run the overwhelming risk of being born into the oppression of grinding poverty and systemic discrimination. Lurking in the background of Rawls’ disembodied prenatal conclave is the assumption that the ignorant spirits are all themselves equal: they are a heavenly democracy, one soul one vote, because no soul is better than any other.

The premise of the veil of ignorance is absurd – how could you be born other than who you are? – but to dismiss Rawls’ argument on those grounds is to risk failing the breakfast question. A better question with which to draw back the veil is to ask whether more equal societies are, in fact, better societies.

There is some empirical evidence in equality’s favour: countries with lower Gini coefficients – i.e. low levels of economic inequality – generally have much higher levels of overall happiness, with less crime and alienation, and greater political stability. This suggests that economic equality is generally preferable to extreme levels of economic inequality.

The logical conclusion from the observation that low Gini coefficients correlate to better societies would be to advocate for full communism. This should make us suspicious, however, because every time communism has been tried it’s been catastrophic, and the same is true in a gentler and more gradual but no less pernicious way of its more milquetoast cousin socialism. On closer examination, we see that there is an important confounding variable. Countries with low Gini coefficients, such as Sweden or Japan, tend to be more ethnically homogeneous than countries with high Gini coefficients, such as South Africa or Brazil: that is, racial diversity is correlated with high levels of income inequality. The inhabitants of homogeneous countries are competing with near-peers, naturally leading to low Gini coefficients since you don’t expect large differences in outcome in the absence of small variances in ability; at the same time the inhabitants of homogeneous communities are also more inclined to cooperate with one another, resulting in lower crime and higher levels of happiness (particularly amongst people such as the Swedes or the Japanese, who are very cooperative, high-trust peoples).

If we look at what has happened in our own societies as we have tried to make them more equal and, simultaneously, more diverse (which we are obligated to do, because we are all equal), we find that the consequences of our fanatical embrace of total equality have been, without exception, entropic. Our institutions are crumbling under the burden of the self-imposed incompetence of DEI. Standards drop every year in the education system, from kindergarten all the way through doctoral programs. Urban areas have long since decayed into crime-ridden hell zones with broken infrastructure neglected by kleptocratic governments. Public debt has exploded into the stratosphere with nothing tangible to account for it but the endless money pits of social entitlement programs feeding an ever-growing dependent class. Mass immigration from the third world – the denizens of which are morally equal to Europeans in every way, meaning that there are no moral grounds to prefer a country maintain its numbers with its own babies rather than someone else’s – threatens to displace white people from dominance in every single white country. I could go on. I don’t think I have to.

Some believe that the answer to this is simply to force society to accept the overwhelming evidence of human biodiversity. Once it is generally acknowledged that there are real, measurable, and significant differences in behavioural inclinations and cognitive capacity between ancestral population groups, we can implement colour-blind meritocracy, in which individuals will be free to rise to whatever station their specific talents suit them to, while everyone accepts as a matter of course that this means that certain groups will be over-represented at certain levels of society – in practice, blacks at the bottom, Hispanics and low-caste Indians in the middle, and whites, Asians, and high-caste Indians at the top. Don’t pretend you don’t know that that’s how it would shake out. We all know. Even the equalists know.

This hope that equalism will go away if we just shatter the taboos surrounding racial and sexual differences is incredibly naive. It gives too much credit to equalists for their readiness to change their minds in light of the evidence of their senses, which they’ve been happily ignoring for generations. Or, it doesn’t give them enough credit for their ability to adapt their demands to an evolving ideological context. If society broadly accepts that blacks are cognitively disadvantaged in comparison to almost every other human population for genetic reasons which are insensitive to education and entirely ineradicable by anything short of centuries if not millennia of strictly imposed eugenic developmental vectors, equalists will not throw up their hands and declare that conservatives were right all along about ‘equality of opportunity, not equality of outcome’. How can you even have ‘equality of opportunity’ when some are born at a genetic disadvantage? So they will move the goalposts, and start talking about ‘genetic privilege’. You didn’t earn that DNA, you know. Do you think those alleles make you better than me?

That sounds absurd, yes, but you have to remember, equality is absurd. It always has been.

And equality is a particularly poisonous form of absurdity.

The Power of Equality

The psychological mechanism that lends equality its allure is Nietzsche’s ressentiment: the curdled envy felt by those who know they are botched products of nature, in the sense that they are inherently weaker, less beautiful, less talented, less healthy, less biologically fit than others, to such a degree that they will never, under their own power, rise to the top. Despite these disadvantages they desire power, they want to be on the top. Contemporary academic theorists all but throw this in your face with their position that all discourse, all language, all scholarship, all science, all philosophy, all religion, every word ever spoken or written, reduces to elaborate justifications for one person or group to have power over another, so what do you think they’re doing themselves? Using their words to gain power, obviously. They aren’t strong enough to take and keep power directly, so they must use trickery. They need to convince their natural superiors to believe in things that aren’t true, things whose inevitable consequence is to put them, and not someone else, in charge ... ideally in such a way that they can claim not to be in charge at all. They subjugate their victims by getting them to believe in false abstractions.

If this characterization of the desire for equality as emerging from envy strikes you as uncharitable, consider the emotional dynamics of the Yarvin-Allen debate. Yarvin certainly doesn’t believe in equality, yet while he could not resist trollishly toying with his overmatched opponent, he was gracious and polite throughout. Despite Allen being in every formal sense Yarvin’s professional superior, Yarvin did not show the slightest trace of envy towards her position. Conversely Allen, who claims to believe in the universal equality of man, clearly did not actually consider Yarvin her moral equal: she treated him contemptuously, as something unclean, something beneath her, like a perfumed noblewoman who’d stepped in something unpleasant. This seems oddly incongruous with her own professed ideals ... just as Yarvin’s courtesy seems, at first glance, out of step with his elitist embrace of hierarchy. Shouldn’t Yarvin have been the arrogant one? And yet there is no real paradox here, once you see that Allen’s ideals are born of envy, not of love, and that underneath the brittle facade of her professional persona with all its honours and accolades and privileges she hears the inner whisper of that troublesome imp, Imposter Syndrome, which by academics’ own reports haunts every hall of higher learning these days. She acts the noble, but knows herself the peasant, and so overreacts with exaggerated scorn when she encounters one she knows to be her natural better ... one whom she envies.

Allen’s entire demeanour indicates that she does not really believe in moral equality. She considers Yarvin to be morally inferior to her, precisely because he is her superior in more natural ways. She resents him for this, and hates him even more deeply for refusing to play her language game in which they both pretend that the two of them are equals. When she says she believes in equality, she is lying. She is lying because this is the lie that gives her power.

The goal of the equalist priesthood is not to lift everyone up to the same exalted level. Of course they pretend that this is their motivation, but that is impossible, and they are perfectly aware of that impossibility. No matter how much ‘education’ you provide a child with Down’s syndrome, he will never master tensor calculus. However, it is simplicity itself to drop the prodigy on his head until any possibility of his ever solving the Einstein field equations is precluded. Voila, equality. The envious desire what others have, and if they cannot have it themselves, they desire to destroy it, so that no one can have it. Equalism pulls everyone down to the lowest common denominator, then lowers the denominator, and keeps pulling.

Consider the results of integrating black and white children in the school system, a program that was so popular when it was first implemented that it had to be carried out at bayonet-point. Integration didn’t improve the grades of the black kids, but introducing large numbers of black kids into white schools was ruinous to the education of the white kids. When the white kids failed to be dragged down all the way to the level of the black kids, their parents were told to stop reading to their children, to avoid giving them an unfair advantage. When black kids became discipline problems at greater rates than white kids, the Obama administration’s Department of Justice threatened federal investigations on the grounds of disparate impact, effectively ordering schools to turn blind eyes to the infractions committed by black kids, while enforcing disciplinary standards on the white kids with increased severity in order to ensure that similar fractions of white and black kids were punished. When white kids sought to obtain something resembling a reasonable education in honours programs whose academic entry requirements were natural barriers to the black kids, the equalists started shutting them down for being insufficiently diverse. None of this is helping the black kids, whose educational performance has not improved in the slightest, but the white kids are sabotaged at every level. POSIWID: sabotaging the white kids is the purpose.

Equalism is a Procrustean lawnmower, cutting the tall poppies to ensure that they do not stand above the rest. It flattens all distinction by making any divergence in talent or ability functionally meaningless. The purpose of this is not that the children will play nicely together and share their toys, though this is invariably how it is expressed. It is certainly not to eliminate hierarchy: hierarchy is ineradicable. It is, instead, to make social status a pure function of the arbitrary whims of those who assign social status, i.e. the preachers of equality.

A beautiful woman is not beautiful because she was born with excellent genes and pays meticulous attention to her appearance; she is beautiful because the longhouse matron tells you she is beautiful. A brilliant artist is not brilliant because his mind can catch the ethereal spirit of the genius loci and channel the energy of that muse into a creative intuition fed by divine talent and honed by years of patient practice; he is brilliant because the longhouse matron tells you he is brilliant. Any of you can be beautiful, any of you can be brilliant: you’re all just the same, and it is the longhouse matron who decides which of you to elevate above the nondescript biomass. If the longhouse matron tells you that an obese landwhale is beautiful, she is beautiful; if the longhouse matron tells you that a Haitian drug addict smearing HIV-infected feces on a canvas is a brilliant artist, he is a brilliant artist. Nothing about yourself, nothing you do yourself, no combination of inborn ability and acquired skill, has any impact on the outcomes of your life: your success or failure is all up to the mood of the Earth Mammy’s high priestess, so you’d best appease her appetites with appropriate sacrifices, particularly when it’s that time of month.

Obviously the priestesses of this cult will not be talked out of belief in the very precepts that are the basis of their power. The clients of the cult will not be talked out of it, either, for the same reason. But these groups do not retain their hold on the social order through any real power of their own. The priesthood’s power is a function of widespread belief in the axiomatic truth of moral equality, in particular amongst those parts of the population who, in the absence of this belief, would naturally rise to the top, but due to their acceptance of it, are made to acquiesce to their status as beasts of burden for their natural subordinates.

Many chafe under this tyranny. Their instincts cry out against it, and some – after overcoming the resistance of several lifetimes of emotional programming – come to reject the most facially ridiculous inferences of the doctrine. But even then, it is incredibly difficult to shed that sense that in rebelling against equality, one is doing something fundamentally wrong, that one is in violation of some categorical imperative written into the moral law of the universe in words of holy fire. This is, I think, due to the deep imprint left by many centuries of spiritual indoctrination. Thus you find people saying things like, “Well of course in a perfect world everyone could be equal, but...” as a preface to some noticing of the natural inequalities that pervade the real world. Yet the more ‘equal’ we have tried to make society, the worse it has become, so would a world in which everyone was equal really be perfect?

The doctrine of outcome equality called ‘equity’ is the poison fruit of the diseased tree of the belief in biological equality, which sprouted from the cursed seed of political equality, which was planted in the sweet-smelling but toxic soil of spiritual equality, which is itself the mulch of the resentment and will to power fermenting in the envious hearts of the botched.

To remove this overgrowth of noxious weeds it is necessary to dig down to the root, and pull it out.

We’re about one third of the way through this absolute doorstop of an essay, and as is my occasional wont I am interrupting your experience with what I am sure is an unwelcome reminder that these textual tokens were not belched out by my own ChudGPT, hand-trained to excel in the production of commodified racism, but was in fact written by an actual human being who has spent a very great deal of time composing a treatise that, perhaps ambitiously, perhaps delusionally, perhaps arrogantly, perhaps even tendentiously, but at least I hope entertainingly, proposes to assault the basis for one of the core precepts of liberal moral philosophy. That’s several hours a day, every day, for several days on end that has gone into this. Without taking weekends off, either: Saturday and Sunday are just other days of the week for me, at least when I’m buried in a project (I will freely admit that when I’m not, Tuesday is just another day of the weekend). Do you have any idea how long it takes to edit a document this long? To revise it, rewrite it, add to it, rearrange it, over many interations as I polish the text to the point where I’m prepared to share it with the world? Just reading it takes a couple of hours.

There are a lot of writers who would put everything that follows behind a paywall. That’s where the real meat is ... the preceding is really just a sort of introduction. In any case, you know I’m not going to do that, because I am vain and addicted to attention, and so want people to read what I write, and paywalls are death to attention, but also (I flatter myself) because it is important to me that the ideas contained in this linguistic signal propagate through the noosphere. So, you can take shameless advantage of my vanity and my attention addiction, and keep reading for free. I won’t stop you. You gain nothing at all from becoming one of the elite patricians who support this blog. Aside from my gratitude, of course. And that knowledge that, by becoming a patron, you join the ranks of the elect.

And now, back to the show.

Equality is a Linguistic Abstraction

Outside of the Platonic realm of mathematical abstractions and fundamental particles, nothing whatsoever in this world is actually equal in the sense of being ‘the same’, which is the only sense in which ‘equal’ has any meaning at all. Yet we pretend that there are things which are the same as a matter of course. We use one word, ‘rock’, to describe a vast number of mineral conglomerations, each of which is distinct in terms of its size, shape, density, composition, and so on. We call every nebulous condensation of water vapour in the sky a ‘cloud’, yet I am sure that you have never, not once, seen two clouds that are exactly identical. There are of course similarities within categories and differences between them: all clouds are insubstantial, while all rocks are hard, and though rocks and clouds might both block the light of the Sun, you’re unlikely to get much water from a rock.

Equality is a phantasm produced by language, a trick we play on ourselves. We use one word, ‘rock’, to refer to a broad range of objects, and thus our minds assign a certain sort of sameness to them. We assume, without really thinking about it, that the use of a word to refer to a thing or an act or a quality means that everything to which that word applies is fundamentally the same. This is necessary. Human language cannot function without the fictitious equality imposed by symbolic categorization.

Of course, vocabulary can become more granular. Rather than simply saying ‘rock’ we can say grain, pebble, stone, boulder, hill, mountain; we can deploy the entire minerological vocabulary to speak of granite, sandstone, limestone, basalt, anthracite, and so on. This makes our language more specific, our categories more precise, but we are still fundamentally playing the same game here, and without thinking about it will assume that one ten-carat diamond is identical to another, when in fact, they are not. No matter how similar two things are, they are always, when you look close enough, at least slightly different. No matter how precise our words become, they can no more capture the endless variation of the matterium than the lightning strikes fossilized in fulgurite can capture the nature of lightning.

Language tries to escape from this trap by the use of names. By attaching a proper noun to a person, a place, a thing, or an event, we assign it a singularity, a uniqueness: it is just what it is and nothing else, belonging to a category of one. Even this fails, however, once we consider time. We call the river Caesar crossed the Rubicon, but it was no more the same river he stepped into when he stepped out of it than Rome was the same Republic. Everything in the universe is a process, a patterned flux of matter, energy, and information. Most of us carry one name for our entire lives, but the ‘you’ who finishes reading this sentence will not be quite the same ‘you’ as the ‘you’ who started reading it, nor are you exactly the same person you were yesterday, or a year before, or a decade before that. It is in this sense rather misleading even to use names, as these imply a sameness in time which does not, in fact, exist.

I’m not saying that you should wiggle an icepick around your angular gyrus to free yourself from the terrible spell cast by language – language is very useful. After all, without it, I wouldn’t be able to write this, and you wouldn’t be able to read it, which would be most unfortunate because writing is how I support myself.

The point is simply to establish that equality, sameness, is a useful fiction that is rooted very deeply in the neural architecture that enables your human brain to process language. The world we actually inhabit is an engine for the production of difference. It excels at the game of ensuring that no two parts of itself are ever exactly alike, whether in space or in time. The cosmos never repeats itself, though it does like to rhyme – it uses the same patterns again and again, which is why language works in the first place.

This is one of the fundamental cognitive tensions of the human condition, a predicament from which we can never escape. Our senses reveal a world of endless variation, in which no two things are alike either in space or in time, while our language forces us to group the phenomenal world into categories based on similarity. Your eyes and hands tell you that you have never seen or touched one rock that matches another, yet Wernicke’s area stubbornly continues to believe in the reality of the Platonic concept ‘rock’ ... and indeed believes that this abstraction is in some sense more real than the phenomena which it groups together under one label.

In similar fashion, the cultural belief in ‘equality’ persists despite every single sensory datum informing every single human who has ever lived that ‘equality’ is a lie. This is why simply harping on about racial IQ statistics or FBI crime numbers or whatever isn’t going to kill equalism: the reality of inequality has been staring everyone in the face, partisans of equalism no less than its opponents, since the seed of the concept was first articulated by whoever wrote the Book of Genesis. It is just the sort of abstraction which most appeals to our minds, a simplifying abstraction, a useful abstraction ... and in a sense, the original abstraction, from which all other abstractions are derived. You cannot do mathematics without the equal sign. You cannot even form concepts without categorizing things by similarity. Yet in the final analysis, equality is an abstraction: it isn’t real.

Distinction in Value

Since nothing is equal, it follows that in almost any circumstance you can envision, some things are better than others.

‘Better’ is of course a subjective evaluation which emerges at the intersection of the intrinsic qualities of things and the uses we wish to put them to. If you want to knap a flint hand-axe, you might rank rocks by their size and composition, according to how easy to handle they are, how easy to locate, how far you have to walk to find them, their degree of impurity, and so on, with the best rock being the rock the meets the sweet spot of fitting easily in your hand, requiring the least effort to obtain, and having the least degree of impurity. If on the other hand you intend to drop a rock from a great height in order to crush the skull of an invader from a neighbouring tribe in the valley below, you will sort the rocks differently, probably preferring rocks that are rather larger, though not too large to lift, and maybe preferring not to use flint at all (since that’s best kept for making hand-axes).

Similarly with human beings: if skill at knapping blades is at issue, your tribe sorts itself according to who has the most nimble fingers, the keenest eye, and the greatest skill; if dropping large rocks from great heights is the task at hand, you sort yourselves by size, upper body strength, and aim.

It’s clear enough that when it comes to any given task, there are materials that are better and worse suited, tools that are more and less appropriate, and individual humans who are more and less capable in their performance. But surely, across the full range of tasks that a human being might undertake, one cannot say that this human is better than that human in any absolute sense?

Isn’t living also a grand task, however? One which encompasses, naturally, many smaller tasks ... but every task can be broken down into components, so living isn’t special in that regard. Should we not expect that some humans are simply better at the grand task of living than others? And is that not in practice exactly what we see?

An obvious objection to this is that the purpose or meaning of any given person’s life is only up to them to define. How are we to say, from the outside, whether the artist is superior to the supermodel? The soldier to the scholar? But even in this frame, with the excellence of each life being judged entirely subjectively according to each individual conscience, there are those who are better at living up to their personal ideals, reaching their personal goals, being the person they want to be, than are others ... and as a practical matter, people tend to recognize that. The charming mafioso gliding through life with impeccable sprezzatura is more impressive to most observers than the frustrated composer grinding through a miserable existence as a depressed branch manager at Panda Express, precisely because the rogue is very good at being what he is, and the composer isn’t. On the other hand, the brilliant pianist is clearly superior to the petty street thug choking to death from too much fentanyl which he swallowed after getting the cops called on him for passing off an obvious counterfeit bill to a skeptical cashier. We recognize ‘success in life’ in myriad ways; it may be difficult to define precisely, but like pornography, everyone knows it when they see it.

Just as there’s no quantifiable metric by which we can say that one thing is pornography and another thing is art, it does not follow from positing that some humans are more valuable than others that this is necessarily something which can be measured. Like the judgment as to which vista is more beautiful than the other, which food more delicious, which novel’s plot the most gripping, the evaluation of something so complex as human value is not something that can be reduced to a number. Nevertheless, that does not mean that the distinctions themselves are imperceptible. To the contrary, the unquantifiable qualia are the most important distinctions that there are.

Nothing in the universe is equal. Every intersection of that variance with the value structure imposed by human utility leads to a ranking from worst to best. It follows directly from this that there are better and worse humans: humans who are more, and less, valuable.

Imago and Similitudo

From a spiritual perspective, you might say that humans are sort of like God’s tools, which He uses to do His work on the world. Some tools are better suited to His tasks than others; they are better tools; they are obviously worth more. QED. Game over, right? Unfortunately, no. This functionalist, utilitarian framing of the question doesn’t really get to the heart of the problem of moral equality.

The value judgments from which utility are generated are inescapably subjective. There may be a broad agreement that the view from the top of Victoria Falls is stunning, but you can usually find a recalcitrant curmudgeon who remainds unmoved by it, and prefer the aesthetic merits of eggshell white paint drying on a flat wall. Beauty, as they say, is in the eye of beholder, and for all the attempts to quantify beauty as the presence of symmetry or the golden ratio or some other mathematical property, anyone who’s ever talked to a zoomer about Zendaya will know the truth of this statement. This opens the door to a perspectival relativism that destroys value itself: if value is a purely subjective projection upon the world, but there is no privileged frame of reference, with every perspective as valid as every other, then value is an illusion. There is an equality of sorts to be found here, but it is only the equality of the void. All things are equally beautiful, because beauty does not exist. All humans are equally valuable, because the value of every human is nothing.

One might however find an escape from this in the observation that while tastes vary, the ability to have tastes is a universal. In this case the equality of man would be found in his universal nature as the value-creating organism: it is in the subjectivity of man, that interiority which projects value onto the variability of the world, a capacity possessed by all men, which makes men equal. This brings us to the more subtle idea from which the notion of the equality of man was shaped: that man is the clay in which the divine imprint, the Imago Dei, is laid.

The Imago Dei is usually conceived of as a combination of those spiritual and intellectual qualities which are unique to mankind, distinguishing the human from the animal: man’s possession of logos or rational intellect, his free will, his relationality, his self-awareness, his role as a steward and co-creator of Creation, and his eternal life after death. The rational intellect gives man the ability to understand and appreciate the natural law. From free will comes mankind’s moral agency: because man can choose, his choices have a moral valence. Relationality means that man has the capacity to love, most importantly including the capacity to love God. Mankind’s creativity reflects God’s role as the Creator. Self-awareness means that man can reflect on himself, see these qualities in himself, and therefore direct them and foster them, a capacity which is itself inseparable from his freedom of will. Since all of these properties partake of the infinitude of God, the Imago Dei carried by the human soul is also of infinite value.

Thomas Aquinas, with his characteristic sophistication, made a careful distinction between the image or imago of God and its likeness or similitudo: the block which leaves the print and the paper and paint which hold it. The imago, given its unitary origin, must necessarily be the same for all, but the similitudo is, as a matter of course, different in every individual case. All reproductions of an image are flawed to some degree; some are more flawed than others, and some will provide a better representation than others, but the underlying template is identical.

This distinction had its origins in Genesis 1:26-27: ‘And let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness’. Reading significance into every carefully chosen word, Aquinas believed that the distinction between image and likeness must therefore be meaningful; whether or not this was an over-interpretation of the use of synonyms for rhetorical effect, it led to an interesting philosophical insight.

The idea here is that since the source of the Imago Dei is the same for everyone, and since its basic properties are identical, this establishes a basal level of equality for all mankind. This is the root argument for the moral equality of man, for universal dignity, universal human rights, all of it. There are other theological arguments for equality – for instance, that Christ’s sacrifice opens the door to redemption to all without favour – but the Imago Dei is the most fundamental argument, and it is the one that has been most widely adapted by secular philosophers to argue for moral equality. John Locke leaned heavily on its support when he invoked the universals of human nature, such as the capacity for rational thought and moral reasoning. Immanuel Kant also grounded the equal and universal dignity of man in his nature as a rational being.

The imago, in Aquinas’ description, is an ontological property, something which simply exists at the core of what mankind is, which distinguishes him from all other entities in Creation. The similitudo, by contrast, is teleological: it is a developmental quality by which man can become closer to God, which is affected both by inborn variation in talent, ability, and disposition, and by the choices and experiences a man makes during his life. The imago establishes the potential (which is infinite), while the similitudo (which is finite) describes the level of actualization of that potential. There’s a hint here of the seeds of the iron-clad progressive faith in education as the answer to the world’s problems, that if only everyone can be taught the correct things in the right way then all distinctions in ability and behaviour can be overcome.

The Imago Dei doctrine does not state that all humans are equally rational, loving, or creative. The degree of rationality is in the similitudo. Rather, the doctrine holds that because humans possess these capacities at all, they are in that sense the same, that in that sense they partake of the divine, and that since these qualities are of immeasurable worth, all humans are of equal (and limitless) moral value in the eyes of God.

But that begs the question. Are the properties associated with the Imago Dei actually, in fact, universally present throughout Homo sapiens? Or is this simply an assumption that Augustine made, which has been picked up and amplified by later generations of secular philosophers, whose social circles were largely populated by men very like themselves ... European, scholarly, intellectual, and prone to abstract theorizing? Is this all just the same kind of mistake psychologists made when they drew all of their assumptions about human nature from contrived experiments conducted on their WEIRD American undergraduates?

There are certainly those who do not seem to embody all or even any of the properties of the Imago Dei whatsoever. Essential psychopaths, for example, are wholly incapable of love; they do not create, but only destroy; what rationality they possess is invariably turned towards deceit, manipulation, and coercion in service of their base carnal drives. It is impossible to reform them: all attempts to do so fail, accomplishing nothing more than to teach the psychopath to construct a more convincing mask of sanity with which to manipulate his victims. It is therefore impossible for them to turn to God. Can a psychopath even be said to have a soul, in the sense that we usually mean the term? Did Jeffrey Dahmer have the Imago Dei?

What about Homo naledi? Or Australopithecus afaransis? Australopithecines were almost certainly not much smarter than great apes, but the paleoarchaeological record suggests that neanderthals had fairly sophisticated tools, and may well have mourned their dead with ritual funerals, suggesting some conception of the afterlife. Where along the way did the hominid lineage become human? Where is the line drawn, at which we can say that at this place, there is no Imago Dei, but at that place there is?

This parallels the debate over consciousness: is it something that humans have, and nothing else? Or is consciousness more similar to a dimmer switch, becoming brighter as one ascends the hierarchy of being, but with a trickle of current flowing in even at the level of the fundamental particle? Panpsychists have long pointed out that if consciousness is present at every level, if it is simply another property of matter, than the ‘hard problem of consciousness’, the question of how lifeless matter becomes infused with spirit, disappears. Insofar as ‘consciousness’ can be taken as a synonym for the Imago Dei – and the two do seem to be largely synonymous – would that not suggest that even a meson also has the Imago Dei? As well as a mosquito, a mouse, and a monkey? The likeness may vary enormously in quality, but if moral equality is the halo cast by the image, then surely we would have to conclude that a mouse is morally equal to a man. As would be, for that matter, a meson.

And indeed we see that the equalist superstition has led some to conclude exactly this.

Moral equality between mice and men is clearly an absurdity. Augustine resolved this by rejecting the suggestion that animals might also hold the Imago Dei on the grounds that they lacked the rational intellect, which was the sole possession of humans. But I am not so sure that this is completely fair to animals. Mice after all are quite capable of forming emotional bonds: they demonstrate tenderness and affection with one another, and they fiercely protect their young. It can therefore be said that they can love, in a sense. Mice demonstrate the ability to learn from their environments, for instance by memorizing complex mazes, and they deploy a certain degree of planning in pursuit of goals such as obtaining food, as when they manage to take the cheese without getting caught by the trap: they can therefore be said to have some glimmer of rationality. They participate in a limited way in the co-creation of the cosmos, for instance by building their nests.

Speaking of nests, are we going to pretend that bower birds don’t exhibit a remarkable degree of artistry in the construction of their mating bowers? Bowers vary hugely in quality. They take years for bower birds to learn how to build. Building a bower is instinctual, but the form of each bower is very much the unique creation of each bird, with its elements being selected for patterns of texture according to subtle aesthetic criteria that only the bower birds themselves understand.

And then we might point to Koko the gorilla, who after mastering a sign language vocabulary of around 1000 words was shown to be perfectly capable of rational thought, affection, and, yes, creation. Not at the level of a Renaissance master, obviously, the Imago Dei argument is unconcerned with the level.

Did Koko have the the Imago Dei? If not, why not? Koko’s tested IQ was 80.3, certainly not as high as the Eurasian average, but apparently higher than that of the average sub-Saharan African, low-caste Indian, or Australian Aboriginal, and certainly much higher than someone with Down’s syndrome. That IQ might well be overstated, but the Imago Dei doctrine insists that moral value isn’t tied to intellectual capacity in any case: we don’t say that someone with Down’s syndrome isn’t a person just because they aren’t very smart. It isn’t tied to speech: a deaf-mute still has the Imago Dei. Are the grounds for possession of the Imago Dei then simply genetic, with Koko excluded on the basis of her chromosomes? But then Down’s syndrome is a chromosomal birth defect – they have an extra copy of chromosome 21, giving them 47 rather than the usual 46 chromosomes – meaning in that sense we might say they are not even properly human; while at the same time the genetic distances between Sub-Saharan Africans, Australian Aboriginals, and Eurasians are considerable enough that, were we to measure those differences within geographically isolated populations of any other species, we would declare those three branches of Homo sapiens to be distinct species without a second thought. Yet all three are said to have the Imago Dei.

It is not really rationality alone that sits at the core of the moral equality conferred by the Imago Dei. If it was, we might be forced into the position of conferring moral equality onto the unkempt piles of linear algebra we call artificial intelligence. It is also that the rational intellect enables one to engage in moral reasoning, and therefore to understand the difference between right and wrong, while free will gives man the ability to choose between the two. Both moral reasoning and free will have long been held to be uniquely human capacities, but this is clearly not the case. Koko was very gentle with her kitten, All Ball, to whom she would sign things like ‘Koko love’.

Koko also passed the mirror test, thereby demonstrating self-awareness; many other animals have passed this test, as well. Self-awareness – the ability to reflect one’s awareness back upon one’s own consciousness – is the key capacity that enables the will (which is possessed by all life) to be free, as it allows one to really choose. If Koko was self-aware, Koko had free will.

There’s no doubt that humans, as a species, possess these abilities to a far greater degree than other animals. You will not find animals weighing the moral implications of clear-cutting a forest in order to provide the lumber with which to build houses for the homeless against the moral cost of destroying a beautiful woodland, for example. However, it seems far from obvious that humans are uniquely capable of moral reasoning. When your dog chews up your slippers, and then slinks away to hide from you when you come home, he knows full well what he did, and he furthermore knows that what he did was wrong: he lost himself in a moment of passion and destroyed something that belonged to his good friend, and he feels bad about that, because he knows he probably could have controlled himself better.

While there are many examples of animals engaging in moral reasoning, it is also far from obvious that every exemplar of Homo sapiens possesses the capacity. There was an interview a journalist conducted with some South African men, in which he asked them about rape, a subject which excited great enthusiasm in them. When he pressed them on the matter of rape being wrong because women do not enjoy being raped, they agreed that this could be troublesome, as she might make loud noises that attract the attention of the police. In terms of consequences, the only ones that they could perceive were that they might get AIDS, or accidentally impregnate her, which would annoy her father. They showed no evidence of the ability to empathize with the hypothetical victim of their attentions, interpreting any pain she might feel as merely a potential source of inconvenience to themselves.

It would probably be going too far to say that those South African men were wholly incapable of moral reasoning, but to whatever degree they are it is hardly distinguishable from what might be expected from an animal. You could maybe try explaining things to them, but I doubt you’d have much success. Do they then possess the Imago Dei? Or are they animals who can speak? And of course, this is not only a question of intelligence, nor is it a matter of race: there are a great many psychopaths who are highly intelligent, yet wholly lacking in empathy, utterly incapable of engaging in any form of moral reasoning that treats another being as possessing an interiority that they can relate to as though it were their own. When they model the minds of others, they do so as cats do when they stalk a mouse.

Is Koko’s moral value the same, then, as Jeffrey Dahmer’s? Is it less? Just because she wasn’t born H. sapiens? That hardly seems sensible. Would we really sacrifice a sweet, kind, lovable Koko to save a calculating, sadistic, hollow-souled Dahmer? Most people would not sacrifice their dog to save a Dahmer, even if it had just eaten their slippers, and if they would I have such severe reservations about their ethics that I don’t think I’d want to associate with them.

If we assume that, as Yarvin put it, the Imago Dei is a Boolean quality, trying to pin down exactly where in the biological kingdom it can be said to appear, and where it is absent, turns out to be extremely difficult to do. There’s no reasonable definition of the concept that can simultaneously exclude all non-human animals, while including all humans. The same problem appears when we consider the evolutionary development of Homo sapiens, which of course neither Augustine nor any theologian until the 19th century knew anything about.

The easiest resolution to this conundrum is simply to declare that Augustine was wrong: the Imago Dei is not a Boolean property belonging to human beings and nothing else, but a continuous one, which is possessed at the very least by all biological life right down to the level of the paramecium. The difference between humans and paramecia isn’t that humans possess the imago and paramecia don’t, but that humans enjoy a much higher level of similitudo, with a capacity for relationality, creativity, awareness, and ratiocination that compares to the paramecium as the radiance of the Sun to your laptop’s charging LED.

But if the Imago Dei is universal, we have no choice but to abandon the theological argument that it is the basis of human moral equality ... unless we are willing to accept that every single bacterial cell dwelling in the dark depths of the deep hot biosphere has the same moral importance as a human being. Did you take antibiotics the last time you got an infection? Murderer.

To whatever degree that a continuously present imago can be said to impart moral value, it is necessarily a vanishingly small degree, not really rising above a sort of vague respect for existence itself. Which is not an unimportant thing, indeed I don’t think we have nearly enough respect for existence, but it’s no basis for a social order. It follows from there that the similitudo must necessarily confer the lion’s share of moral value, since it is only in this respect that humans differ from other animals. But the similitudo differs profoundly across humans ... meaning that the price of rejecting the moral equality of man and beast is that there is no basis whatsoever for the moral equality of men with one another.

That does not mean that moral value disappears. I would not say that the moral value of a mouse is zero. If I find one in the field I’m not going to go out of my way to step on it, and indeed, will try to avoid harming it if at all possible. Then again, if mice get into my larder, I’m not going to hesitate before putting out traps ... though I’ll feel a bit of a pang of conscience when I go to collect them (and annoyance if the clever little creatures avoided them while still managing to purloin the cheese). Then again, I will lose no sleep at all over swatting a mosquito, and indeed will sleep more soundly once the damnable blood-sucking pest isn’t buzzing past my ear ... this despite knowing full well that all she’s trying to do is collect the food necessary for her to have babies, a goal with which anyone can sympathize (even if, on reflection, most people would prefer that she not have babies).

Unequally Infinite and Infinitely Unequal

A core Christian belief, adjacent to the Imago Dei’s argument for equality, and which remains implicitly in the background of secular moral philosophy, is that every soul is of infinite value. The argument goes that souls are divinely endowed, are eternal and immortal (i.e. infinite in time), are redeemed through the infinitely precious sacrifice of Christ on the cross, and are each in principle equally capable of knowing and loving God (which is itself of immeasurable value). Just because one soul has turned away from God and is not presently redeemed, does not mean that it can’t, at some point in the future, return to God, thus even the unredeemed souls of the worst sinners are of infinite value given their future potential for redemption (even if that potential is infinitesimal in practice).

When we encounter infinities we have a tendency to just throw up our hands and say that two infinite things must be equal. But mathematically this isn’t at all the case. For example, infinities can be countable, like the natural numbers, or uncountable, like the real numbers. Which infinity is larger? The countable natural numbers, going from 1, to 2, to 3, and so on to infinity; or the uncountable real numbers between 0 and 1: 1/2, 1/3, 1/4, π/6, 1/√2, e/3, and so on ad infinitum? The answer (at least in set theory) is obviously the uncountable infinity, because (being uncountable) it contains more numbers than the countable infinity. Thus one infinity is larger than another infinity, despite both being infinite.

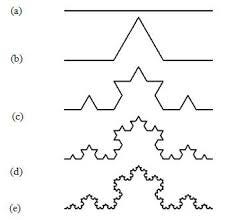

Incomparable infinities abound in mathematics. The boundary of a fractal, for example, is always infinite, despite the bounded area or volume being finite. That does not mean that fractal boundaries are all equivalently infinite. The famous Koch curve provides a simple illustration of this property. This is constructed by starting with a line, removing the inner third, and inserting two more lines into the gap as the sides of an equilateral triangle, each of which is 1/3 of the length of the original line. The process is then iterated an infinite number of times. The length after the first iteration is 4/3 of the length of the original line; after the second iteration, it is 4/3 times that length, or 16/9 of the original length, or (4/3)^2; after n iterations, it is (4/3)^n times the original length. As n goes to infinity, so does the length of the Koch curve.

But what if, instead of deleting the middle third and replacing it with two sides of an equilateral triangle, we replaced the missing third with three sides of a square?

Iterating this an infinite number of times gives the square Koch curve a very different appearance.

Like the classical, triangular Koch curve, the length of the square Koch curve is infinite. However, at any given step in its iterative construction, it is longer than the triangular Koch curve at the equivalent step, because the new length of the square Koch curve is 5/3 times the previous length, whereas the triangular Koch curve is only 4/3 times larger. Thus, both curves are of infinite length, but one of the infinities is larger than the other.

We don’t even need to compare different Koch curves to see this principle of unequal infinities at work. Consider only the first third of the original, triangular Koch curve – that is, the segment spanning the first third of the initial line segment. Because fractals are self-similar at all scales, if you zoom in on this segment, you see a miniature replica of the full structure. It is therefore infinitely long, just like the Koch curve as a whole. But despite being infinitely long, that smaller segment will always be one quarter of the length of the entire curve. The same is true of the first ninth of the original line: after an infinite number of iterations, it too has an infinite length, but that infinite length will always be 1/16th of the infinite length of the full Koch curve. If you keep on zooming in to the left-most edge, then after n iterations you’re looking at a line segment spanning (1/3)^n of the original line. Since this fraction gets smaller as n increases, then as n approaches infinity, the line segment approaches a length of 0: it becomes an infinitesimally small point. Yet that infinitesimally small point supports its own infinitely long Koch curve ... which is infinitely smaller than the length of the full curve.

If two things are infinite, it doesn’t mean that they’re equivalently infinite. By analogy, every soul might be infinitely valuable ... but (with apologies to George Orwell) some might be more infinitely valuable than others. The human soul may derive its infinite value from the infinite value of the divine creator from which it emanates, but in the same way that infinitesimally small segments of a Koch curve are all infinitely long but also infinitely smaller than the infinity of which they’re a part, the infinite value of the human soul can never equal the greater infinity of the worldsoul. Given the ineradicable inequality between whole and part, there is no reason to infer that similar inequalities do not also apply between the parts themselves.

An objection to these fractal analogies is that they are poor analogies: theology is not mathematics. The value of a human soul is not the boundary of a fractal. Theologians did not have mathematical abstractions in mind when they invoked the trickster god of infinity as a garment for the philosophical abstraction of moral equality. It seems hard to believe, however, that theologians did not have mathematics at the backs of their minds. Insofar as they were educated men – and they were, highly so – they would have been conversant with the arithmetical theory of their time. ‘Infinity’ is, by its nature, a mathematical abstraction, which theologians used as a sort of metaphor. When the concept of the soul’s infinite value was first being advanced, the mathematical understanding of infinities was in a rudimentary state. You had a vague sense that there was no upper limit to the natural numbers, an even vaguer sense that space was unbounded, and Euclid’s definition of parallelism as two lines that never converge even if they extend without end, and that was about it. It is not accidental that the mathematical symbol for equality – developed in 1557 by the Welshman Robert Recorde – is two parallel lines, one above the other, as in its inventor’s words ‘no two things can be more equal’.

Serious explorations of the properties of the infinite did not take place until Cantor in the 19th century. We have better metaphors now, and those metaphors tell us that infinity does not imply equivalence in any respect.

Inequality in Time

Even the Christian doctrine of redemption doesn’t seem quite self-consistent when it comes to the doctrine of spiritual equality. To find redemption is to enter a more exalted state than one was in before – one’s current state is better than one’s previous state. Yes, redemption comes from God’s mercy, which is freely offered to all, contingent only on a soul’s decision to accept it. Nevertheless there’s clearly a value judgment being made here, both by the individual soul and by the God from whom Christian doctrine insists that all grace descends. Spiritual growth, development of the soul, is held superior to decay into dissolution and sin. If the soul has been improved by turning to God, and the soul is ultimately where moral value is deposited, it is very difficult to see how there can be any moral equality between the improved state and the previous. The improved soul is necessarily worth more, or else there has been no improvement.

Of course, in the Christian view, the soul is eternal. This opens the door to an extremely low time-preference view of both spiritual development, and the value of the soul: since there is always the possibility that a soul might improve, and since the value of this improvement is immeasurably vast, then if it is viewed from a timeless perspective – as a sort of hyperdimensional object in which all states are simultaneously in existence – then its value is determined by its highest state, rather than its lowest. We still have something of a paradox here, however, because for this upwards development to be possible at all, the soul must value the higher state over the lower, or else it will not pursue it, and that future exalted state will never be reached.

Have you ever noticed how so many leftists are in terrible condition, not only morally but psychologically, physically, and aesthetically? I’m sure you have. It’s impossible not to see. Entropy seems to grab hold of them to whatever degree they embrace equality. They get fatter, weaker, more unhealthy-looking. Their appearance degrades. Their vices take them over. They become lazy and sloppy. The demons of depression and anxiety take possession of them. Their intellects even seem to dull. You’ve probably seen this happen in real time to people you know.

This is no accident. If moral equality is taken to its logical conclusion, then improvement is impossible. You are ‘perfect just the way you are’. To even attempt improvement is to implicitly repudiate moral equality, because it affirms that there is some future state of body, mind, or soul that is preferable to the current state. A value judgment has been made and, worse, acted upon. This is inconsistent with the principle of moral equality, therefore those who commit themselves to this cause with the greatest fervour are dissuaded from self-improvement.

Following the principle that all that which is not growing is decaying, the only possible outcome of ceasing to push oneself to improve, even if only in small ways, is that one starts to fall apart. Step by step one backslides to lower levels, and since no level is preferable to any other – all versions of you are, after all, morally equal – there is nothing to arrest the decline.

This is also true at the social level, and even the species level. If a society is not trying to improve itself, even in small ways, via adherence to some ideal, then it will gradually decline and crumble. Societies, like people, require ideals to reach for, as something to provide a sort of hormetic stimulus, a source of resistance that forces upward development.

Of course, it isn’t at all true that our own society has no ideal. It does: the ideal of equality. But then, because this is a poisonous ideal, the more tightly we embrace equality, the more thoroughly we work out its consequences, the more consistently we put it into practice, the more we write it into our laws, the more rapid our decay becomes.

Inequality Before the Law

Even those who reject equality in its stronger forms often fall back upon a softer variety: political equality, equality in the eyes of the law, the equality of equal rights. This is the idea that the law is meant to be an objective standard, which applies to all without preference. There should be one law, and no man should be above it. There is an analogy here to equality under natural law: those principles of physics which apply to every entity within the physical realm, enforced with blind impartiality by the universal magistrate of cause and effect.

Natural law, however, does not exactly apply equally to all entities. There are hierarchies of natural law: physics applies to everything, but the laws of biology apply only to living organisms. Living organisms are still subject to physics, but inanimate matter is only subject to physics, and nothing else. Everything is bound by law, and as entities become more complex, they are bound by more laws: law building upon law, in an ascending spiral of legal complexity.

The laws binding organic life are more complex than those binding inanimate matter. The compensation for this is that organic life has possibilities open to it that inanimate matter does not: an animal can walk up a hill, but a rock can do no such thing. The animal is not violating physics when it moves against a gravitational gradient: it must burn at least as much chemical energy as the gravitational potential energy it wishes to add to itself (and in practice more, because the conversion of chemical to mechanical to kinetic to gravitational potential energy is not a perfectly efficient process), so it will be tired when it reaches the summit. If there is not a payoff – additional energy in the form of food – at the end of its labours, the animal may die of starvation.