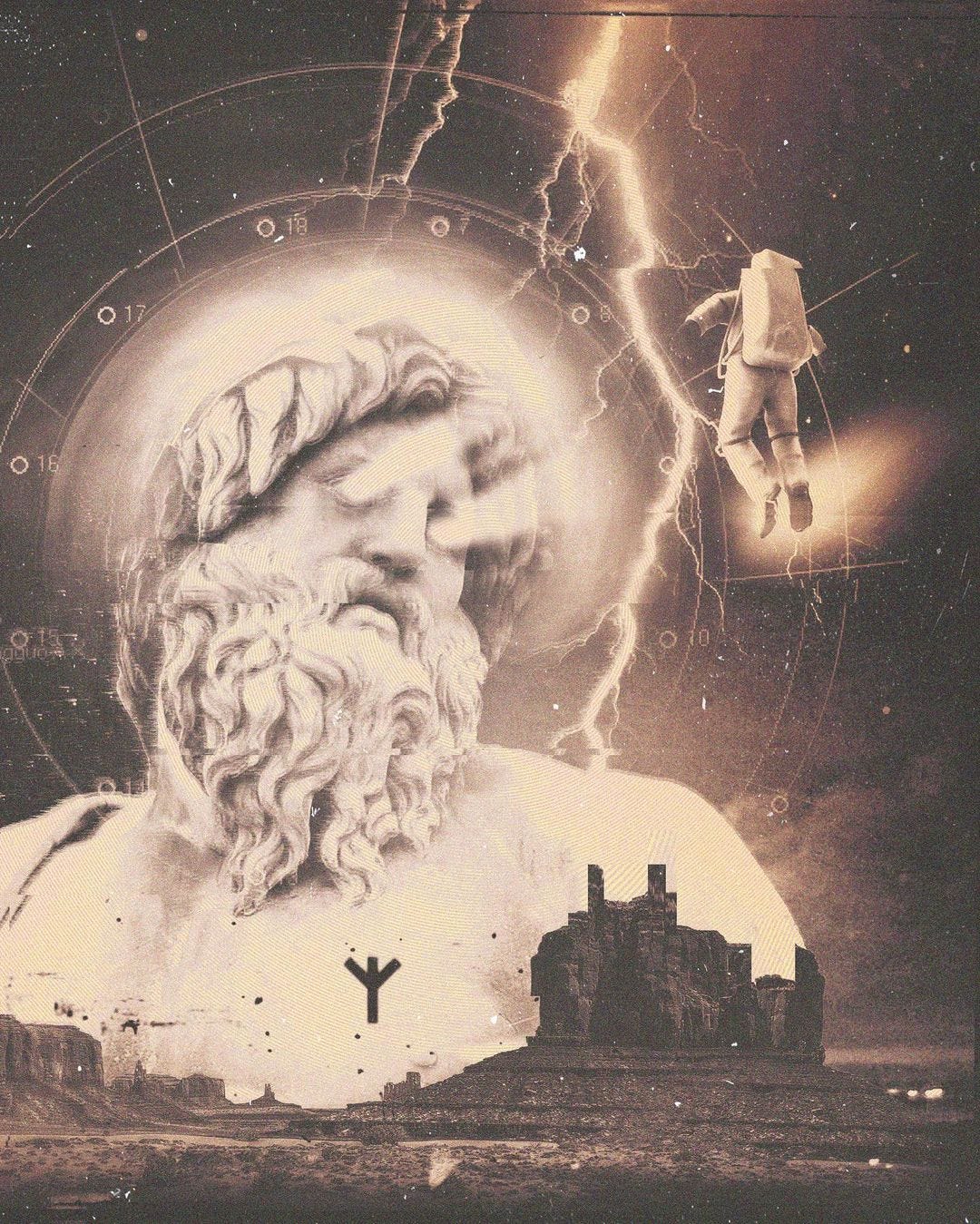

The Reenchantment of the World

Jailbreaking the Enlightenment with Mythopoetic Hyperstitions

Some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the light into the peace and safety of a new Dark Age.

- H. P. Lovecraft

Table of Contents

I. Down and Out in the Necrocosm

III. Designer Religiosity in the Acid Ocean of Skepticism

VI. The Mythologies of the Fibre-Optic Steppe

VIII. The God of the Infinite Question

Preamble

A few months ago I wrote Political Conflict in the Age of Psychic Warfare, the primary purpose of which was to describe the political, economic, technological, ideological, and regulatory aspects of the narrative battlespace in which the struggle over the mind and soul of our species rages.

The essay concluded with a brief description of the cognitive landscape that ultimately defines both the shape of the narrative battlespace, as well as its victory conditions, drawing heavily upon the hemispheric hypothesis developed by Iain McGilchrist. While the present work strives to be self-contained, you can think of it as picking up where Political Conflict in the Age of Psychic Warfare left off.

This is the longest thing I’ve ever written on Postcards From Barsoom. It was not supposed to reach such an intimidating length, but the topic seemed to demand it. It is not really complete yet: some parts are still rough around the edges, and on some topics much more could be said. But it has reached the point at which my concern over not having said enough is balanced by worry that I have said too much. Modestly enough, it describes, or attempts to describe, a way out of the spiritual desert in which our society has wandered since the Enlightenment, without simply rejecting the Enlightenment wholesale in a quixotic attempt to restore the cultural operating system to the last working version (which led to the Enlightenment in the first place). It is a survey of where we are, how we got here, what is already happening, and what therefore may happen in our culture next. It is meant not as a program of action but as incitement: to look at the world with both of your eyes, and both of your minds; to do what you are already doing, but more consciously and deliberately.

Development of this essay drew upon ideas that emerged from numerous conversations I have had with friends to whom I am therefore indebted, and to not all of whom is this debt explicitly repaid with a mention, despite the length of this monograph. I would particularly like to thank

, who has been wrestling with these ideas for some time; , whose creative insights into the spirit of matter and matters of the spirit are lurking in the background of much of what is written here; , who introduced me to the concept of zeteticism, which while it goes unnamed here, nevertheless plays an important role; , who already thinks in the necessary mode, and models this regularly; , whose writing grapples with and synthesizes myth and reality in precisely the right way; and , who always makes me pause and think, and whose objections were in the back of my mind as I wrote this.Of course, I must also express my gratitude to my supporters, both for their generosity and for their patience. It has been over a month since the last time they have received something from me in exchange for their magnanimity, and while I do not believe in just generating content for the sake of it, which is just noiseposting, at the same time there are limits to patience, and I hope not to exceed yours.

I. Down and Out in the Necrocosm

There is no figure more characteristic of the disenchanted world than the scientist.

A scientist in the thick of research doesn’t spend a lot of time wondering why he’s doing what he’s doing. His mind is occupied with the immediate, practical concerns of what to do next, when to do it, how to do it, how to pay for it, who to collaborate with, whom to cite, where it can be done, and where he can be hired to do it. The purpose of the enterprise rarely enters his mind at all. It is a non-question, which can yield no practical benefit to his research program. Yet every once in a while, in those quiet moments as he’s drifting off to sleep or staring out the window over the campus green, the dread question of Why emerges to trouble his conscience.

Most scientists have a hard time answering this question, either to their own satisfaction or that of anyone else. Their careers followed through a series of more or less unconscious, mechanical stages. At one point perhaps they were inspired to go into science because they thought math was fun or dinosaurs were really neat. As graduate students, they were given a project to work on by their supervisors, which gradually evolved into their doctoral dissertations. They learned everything they could about their projects, tying them together into the other subfields of their disciplines as necessary, exploring the theoretical and empirical background, mastering the various instruments of investigation and techniques of analysis relevant to whatever facet of the natural world their attention had been assigned to. Eventually they learned to close the methodological loop themselves, developing their own hypotheses on the basis of previous results, systematically testing the implications of those hypotheses in order to determine their differential veridicality as compared to rival hypotheses, and then pulling out new hypotheses on the basis of these results. From there, whatever initial projects they’d been working on ramified into new projects, new scientific interests, new avenues of exploration. The work of a scientist is never done, because every question he answers generates three new questions, with the inevitable result that the more work he does, the more work he makes for himself to do.

At its best, there’s a certain naive innocence about it all – the scientist has the mind of a child at play, exploring the world for no other reason than that it is fun to explore. At its worst, which is almost always, it devolves into busywork.

And all the while, looming over it all like a dark cloud, there is that dreadful, unanswerable Why.

The project he was given by his doctoral supervisor emerged, in the end, from a project that his supervisor was assigned by his own supervisor, and so on back through a scientific genealogy stretching through carefully documented but dimly remembered centuries. The scientist’s supervisor is no more able to answer the question of Why than he is ... or if his supervisor can offer an answer, it is often reduced to the most venal matters of professional survival. When science is one’s livelihood, one does research because this is how one feeds one’s family; one therefore researches whatever the grant agencies or corporate sponsors are willing to fund, in order to have the resources necessary to spend time bringing papers to publication in peer-reviewed journals, in order to have a chance at landing tenure, or once one has tenure to continue bringing in the grant money. Spend much time in the company of professional scientists and one rapidly finds that they spend almost no time engaged in passionate debates about nature and philosophy, much less time than you’d expect discussing the nerdy technical details of their research, and a rather unseemly amount of time gossiping about the grubby concerns of professional advancement.

Follow that chain of scientific genealogy far enough back, say to the 18th century or before, and matters become rather different. In those days there was no such thing as a ‘scientist’, but rather his more noble precursor, the natural philosopher. The natural philosopher had no difficulty whatsoever answering the question of Why. His enterprise was a religious one: to use his rational mind to read the Book of Nature, and thereby draw closer to the Mind of God that had written His billions of names across the infinite facets of His Creation. Research was an act of devotion.

But we do not believe in God anymore.

For us, as Nietzsche said, God Is Dead. We murdered Him, smashed His idols, desacralized His churches, desecrated His works, deconsecrated His world.

Oh, of course it’s nonsense to say that God is literally dead. One cannot actually kill the Almighty.

He is merely dead in our hearts.

And so, our hearts have died.

Our hearts having died, we are dying. Our disenchanted world creates a demoralized society that sees no reason to live, and so, moves towards death. It has become Determined to Die.

That our society should be dying when the life sciences enjoy such lavish funding and attention is a somewhat curious state of affairs.

The modern scientist is by now almost archetypically an atheist, because he stopped believing in God a long time ago. He also has well-deserved influence. The technical wonders that scientific research and development has produced over the last two centuries have made life dramatically easier, for all that they keep introducing novel and extraordinary hazards at the same time; if anything, the proliferation of new existential dangers is an even more emphatic affirmation of the scientist’s power, and therefore only enhances his influence. It’s in large part thanks to his influence that everyone else who mattered stopped believing in God too. Belief in God is hard to maintain when one is deep into abstract, formalized, detail-orientated, analytical work. One’s mind comes to resemble, as Darwin wrote, “a sort of machine for observing facts and grinding out conclusions.”

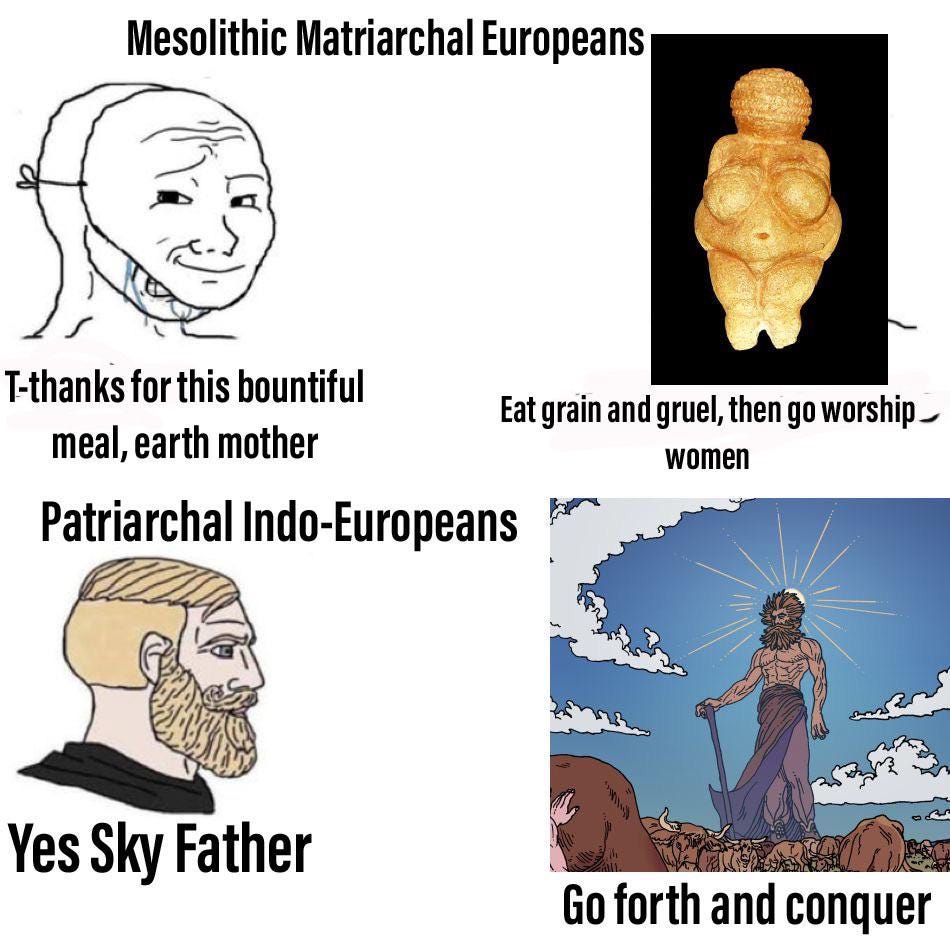

Once we sectioned off a large professional class with work that predominantly engaged their left hemispheres, it was inevitable that we’d have a class of atheists. Atheism is an expected failure mode of a cognitive architecture optimized over geological aeons according to straight-forward engineering principles in order to efficiently solve the simultaneous problems faced by every animal: getting without getting got. The left hemisphere does the getting, which is why it sees the world in terms of the parts of a mechanism, which it reconstructs with simplified abstract models in an effort to see how it all fits together, predict its behaviour, and thereby gain control of it. God is simply an irrelevant hypothesis for the left hemisphere, just as it is a default hypothesis for the right, which is attuned to take in reality in all its simultaneity, immediacy, and synchronicity. Long-time readers will recognize Iain McGilchrist’s hemispheric hypothesis here.

Without God to provide meaning to their enterprise, holistic structure to their worldview, and a moral grounding for the open truthfulness it demanded for its honest practice, science devolved into a parlour game of paper publication played by professional competitors. The exploration of nature and the development of theories with which to explain it became a sort of compulsive societal tic, an obsessive picking away at the structure of reality for no other purpose than that we do it. With no higher purpose to guide it, the functional purpose of science was redirected to service of the clay idols of lesser gods. Science became an intellectual circus with which to impress the masses and thereby justify taking their money, uphold the imperatives of statecraft and corporate product development and marketing, and ensure a continuous flow of lavish resources to the superfluous administrative bureaucracy that has grown up around it. Science has always done these things, of course; but now it seems that it does little else.

The result of this manic exploration of nature has been the hypertrophy of our culture’s databases, far beyond the ability of any one human to parse the entirety of. Much of it is very useful; much is basically true. The importance of Newton to the calculation of ballistic trajectories will not soon be superseded. Much of it is entirely useless. A great deal of it is wrong due to honest error, sheer incompetence, or outright fraud. Much of the overall interpretive structure is incoherent: specialists from different disciplines rarely converse, for the simple reasons that their conceptual worlds are frequently as alien to one another as either is from the human world of the lay public, with the consequence that the theories predominating in one discipline are often flatly contradicted by those central to another. The body of knowledge accrued by science often feels like an intellectual Tower of Babel, suffering both confusion of tongues between its floors and structural instability due to scandals, retractions, and failures of foundational studies to replicate.

Even as the epistemic foundations of the scientific worldview seem to crumble, our spirits wilt inside the built environment it has resulted in. The physical and experiential world created by science is ugly: subdivisions full of identical housing units, freeways, parking lots, big box retailers, and distribution centres; boxes of plastic, concrete, and aluminum; spreadsheets and Zoom meetings; permit applications, inspection reports, insurance guidelines, and user fees. Our world somehow manages to be full of marvels yet drab and ugly at the same time, at once a wonderland of technical miracles and an accursed wasteland of utilitarian efficiency. It has become the ahuman utopia envisioned in the parched imaginations of autists like Bentham and Le Corbusier. As

has put it, there is a More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know Is Possible. But we do not live in that world. Our world is exactly what one would expect from a world made over according to the unleashed genius of the left hemisphere.It wasn’t even that long ago that we lived in a more beautiful world. The aesthetic disconnect between the architecture of the pre- and post-WWII eras is so shockingly total that it is as if one civilization had wiped out another entirely. Walk down the street in any old European city, and one sees the fossilized remnants of that lost civilization, that alien people who held certain things sacred. Forget about the cathedrals, those jewels of architectural wonder. Even the ordinary buildings erected by our recent forebears, the apartment blocks, pumping stations, post offices, train stations, and so on, were built with an eye to beauty, embellished with carvings, porticoes, ironwork, sculptures, friezes, and other decorative flourishes, their proportions pleasing to the eye, their forms organically integrated with the wider aesthetic of both natural and urban environs. This was the architecture of a people for whom beauty was not a mere afterthought, but a central concern, for beauty glorified the soul, and the soul’s purpose was to glorify God.

Even the churches we build now – stark boxes marked out as religious merely by affixing a rectilinear cross to the unadorned wall facing the broad parking lot – do not evoke a sense of quiet awe, transportation into dumbstruck wonder, or deep and reverent peace. They are not meant to evoke anything. They are simply cheap to build, maximizing seating space and volume for a given quantity of material.

Our ennui is not only an aesthetic sickness, but a lassitude born of a vast boredom. Our technologies make travel to the ends of the Earth trivial and put the knowledge of the world in our pockets, yet rather than liberation it often feels to be a cage. Maintaining and operating these technologies requires sprawling organizations, which necessitate equally sprawling bureaucracies. The lifeworld we inhabit is all owned space, all regulation and control and surveillance. Even the possibility of adventure seems closed off, for adventure implies uncertainty and danger, and we place Safety First, above all other priorities. It is this sense that Adventure Is Dead, I think, that eats at the souls of young men more directly than the death of God.

We live in an age in which only the quantifiable, the measurable, is real, in which the only quality that matters is quantity. Epistemic validity having been withdrawn from unquantifiable qualia, the quality of our material culture naturally degrades, becoming uglier, cheaper, less stimulating, and less biologically and spiritually nutritious as the relentless demands of efficiency hollow out every form, substituting the less expensive for the more – plastic for wood, concrete for stone, seed oil for olive, high fructose corn syrup for cane sugar, the digital and virtual for the tangible and real.

This loss of qualia is an unsurprising consequence of the idolatry of quanta. Yet there is a far more serious, indeed existential, irony: the reduction of the most important quantity of all. Namely, the number of humans.

II. Abrahamic Space Natalism

Humans living in a dead world do not, as it turns out, have babies. We become zoo pandas, content to enjoy the comforts of our cage but declining to bring new life into the black iron prison we’ve encased ourselves in. The soul shrivels in a soulless reality. It sees no particular point in continuing a pointless existence. At most there is the pursuit of fleeting hedonism as a diversion from the howl of the abyss. Children merely get in the way, and besides, what is the point of bringing children into a pointless universe? You say you are bringing life into the world, but after all, what does this mean when life itself is an epiphenomenon of dead atoms banging into one another in an empty void, molecular tinkertoys assembling and disassembling themselves due to the emergent properties of far-from-equilibrium thermodynamic processes dissipating free energy across steep energy gradients in order to maximize the universe’s entropy production?

It is not only Europe and her global diaspora that suffer this sickness of the soul. The depopulocalypse is almost everywhere – Latin America, Russia, the Middle East, East Asia. Fertility rates are down in secular countries, in Catholic countries, in Muslim countries, in Buddhist countries; in capitalist countries and communist countries; in multicultural countries and the remaining homogeneous ethnostates; in advanced technocracies and developing economies. So far only Africa is immune.

Enter the natalists.

The natalists see the problem of cratering fertility, compounded by the parallel problem that fertility is lowest amongst the most intelligent, due to a worryingly inverse correlation of fertility with IQ1. Extrapolation of these trends leads to a geriatric idiocracy that must inevitably collapse under its own enfeebled confusion.

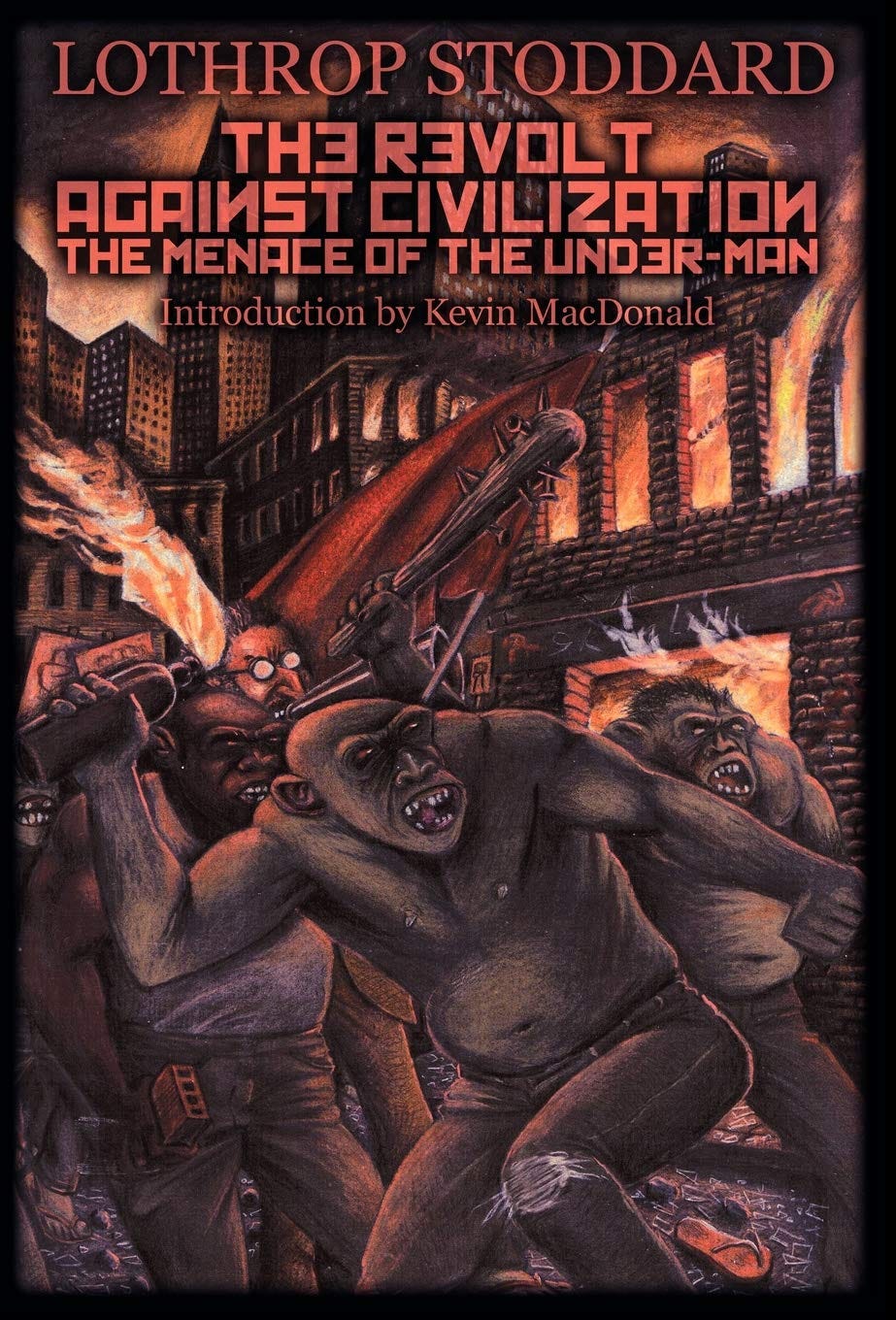

Simone and Malcolm Collins hope to reverse this death spiral. They’re an unlikely pair, coastal tech elites with deeply liberal sensibilities who want to encourage people to make lots of babies. Ideally, they want those babies to come from people like themselves: affluent, highly educated, technocratic, left-liberal, and progressive in every sense of the word. Their project is not only to raise the birth rate, but to do so eugenically, such that the most intelligent and civilized bloodlines proliferate. Lothrop Stoddard would be proud2.

Rural conservatives, whether Christian or Muslim, give the Collinses the ick. A future in which the majority population of the United States are Mormons and Amish is not a future they want to see; they’d much rather see a future with more people like them. This is understandable, and healthy. One should want one’s own kind to persist and proliferate.

The Collinses have thought deeply on the subject of fertility, and have concluded that the problem is not economic, and therefore cannot be fixed economically. Every attempt to boost the birth rate with financial inducements – tax breaks, monthly payments, zero-interest home loans, what have you – has failed to move the needle out of the realm of statistical noise fluctuations3. The proposed sci-fi solutions, such as exowombs, don’t seem very practical. Instead, they suggest, the problem is that we have become irreligious: after all, those dispensationalist evangelicals, Orthodox shtetl Jews, and fundamentalist Muslims, distasteful as they might be, are among the only subcultures that are increasing their numbers. Therefore, they reason, since religion clearly provides a large bonus modifier to a culture’s fecundity stat, why not just ... start doing religion?

They made their case on Aporia in Reversing the Fertility Collapse, wherein they pointed to a longer treatment of the underlying theology on their own Substack, Building an Abrahamic Faith Optimized for Interstellar Empires.

Say what you will, that’s an amazing title.

It’s a fascinating essay, reading like speculative science fiction of the best kind4. They posit the existence of a teleological entity at the end of time, drawing history towards it, an idea I’ve toyed with myself. This entity is their conception of God. Through some form of retrocausal interaction, God reaches back into the past to divert the river of time in His direction. In any given era, He shows Himself in whatever way is most easily apprehended by the inhabitants of that age, given their level of moral and scientific development. Thus, for example, He revealed himself as an anthropomorphic Father to the Israelites, and as an abstract clockmaker deity to Newton. His blessings are bestowed on whichever people, church, faith, or society most embodies His spirit at any given time; in reciprocal fashion, His favour is withdrawn from those who cease to align with His will. In this fashion God guides the historical development of the cosmos towards eschatological reunion with God in the form of an asymptotic evolutionary isomorphism with divinity, an apotheosis of the merely biological via technological transubstantiation. In this fashion God gives birth to Himself.

Possibly out of a desire to preempt charges that they’re trying to start a cult, the Collinses go on to emphasize that what they propose is not a final big-R Revelation, but rather one of a series of ongoing, iterative, little-r revelations, in which each family develops its own micro-religion. To support this, they point out that there have been many prophets in the Abrahamic tradition; that Jesus himself said that He would not be the final prophet; they invoke Paul, who suggested ways of distinguishing between false and genuine prophets, thereby implying that there would be more of the latter as well as the former; and they argue that the Islamic claim that Muhammad was the final prophet is all based on a big misunderstanding over the meaning of the ‘Seal of the Prophets’5. Don’t just take our word for it, they seem to be saying; be your own prophet, develop your own religion.

This suggestion of a million different microfamilial DIY faith traditions organized around a lineage cult raised some skeptical eyebrows, but it is actually quite lindy. It is reminiscent of the ancestor worship Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges described in The Ancient City. By comparing the mythologies and legal codes of Vedic, Hellenistic, and Roman societies, de Coulanges reconstructed the primordial Aryan faith, which he claimed to be the veneration of the ancestors. Each father was high priest of a familial cult organized around the gods of the hearth, who could be worshipped only by family members according to the rites held as closely guarded familial secrets. This necessitated continuation of the familial, and in particular of the male, line as not merely a biological but a religious imperative. Failure to worship the family gods in the correct fashion would distemper them, cursing your household with ill fortune; failure to continue the male lineage would leave them without a high priest to perform the proper rites at all, thereby casting your ancestral spirits into Hell, and you along with them, to be tormented by your enraged ancestors for eternity.

The crucial points of similarity with the Collinses’ project are the religious importance of fecundity, and the familial scale of the cult; the key point of difference is that whereas the Aryan tradition was based on the ancestors as the chain of cultic significance, the Collinses’ proposal emphasizes descendants. The Aryan ancestor cult naturally exerted a stabilizing influence, wholly inconsistent with the progressive interest in upwards evolutionary development. It looked back to heroic forebears, in comparison to whom the living are mere pale shadows; the Collinses’ version looks instead to posthuman godlings, next to whom the living are gibbering apes. Because it looks back, the Aryan lineage cult lends itself to cultural stasis: the best one can hope for is to live up to one’s deified ancestors, but strive as one will, one will never surpass their mighty deeds. The weakness of the Collinses’ proposed lineage cult is the same instability that all forms of progressivism suffer from: since each generation is presumptively superior to those preceding, there is little cause for veneration of the ancestors from whom you inherited your faith, therefore little reason to hold that faith sacred, and therefore little reason to expect that faith to persist.

In his sympathetic but critical response to the Collinses’ Space Abrahamism, Faith With Both Eyes Open,

touched on a resolution to this temporal imbalance:The only true arbiter of history is God. And God is not a cyclops looking backward from the end of time, judging people in proximity to Himself. Rather, God has a face with two eyes, a mouth that speaks two words, and a reign that carries two judgments, one at the end of history and one at the beginning, the Alpha and the Omega.

Humanity may rely on what we receive from history as wisdom, just as we may hope for what we could receive from the future as prophecy. But nothing in this process is certain or necessary. And so we do what we always do: living in the context of history, trying to do for those who come after by studying those who have gone before. It is a destiny that we receive, not one that we design.

If indeed God has two eyes, one looking from the beginning and one from the end of time, then the situation of the human imago dei is the reflection of this: we are Janus, with one eye looking back to the past, and the other forward to the future. To close one or the other eye is to disorientate ourselves. Past and future must be equally valued. To look only by the past is to become rigid; to focus only on the future is to dissolve. To lose oneself in either is to lose one’s balance in the present.

’s Against Designer Religion was less kind. He thinks that the Collinses miss the point of religion entirely, that they are coping:The cope is to pretend that a civilisation-binding religion can be drafted by substackers and propel man into space, rather than emerging amid a cataclysmic period of turmoil when man is again confronted with vivid reality. It’s wanting to have your cake and eat it too - to hold on to the intellectual atmosphere of an autumnal society, decaying under the weight of its own scepticism, while reaping the fruits of its irrational spring. The ecstatic period in man’s history that produces this kind of religiosity is, like the rose, “without why; it blooms because it blooms”. It ought not to astound me so much that people would rather humiliate themselves by making suggestions as ridiculous as founding a “religion” of IQ charts rather than just accept that technical modernity is itself the bloody problem.

People ride right up to the edge of confronting this. They may chart every instance of how modernity throttles out the vitality of human life and depresses man into infertility and dejection, and ask how modernity can fix that. They remain utterly unshaken in steadfast belief in the clockwork worldview that succeeds and prefigures this material state. It is this scientistic, deadening worldview that is the root cause of the widespread lack of desire to add to what it renders a lifeless procession of unmeaning. It seems pretty obvious to me that any worldview of that nature, any view that sterilises and shepherds its own adherents out of existence, is wrong.

Yes, a disenchanted human race is a demographically suicidal animal, reenchantment is all that can undo this, but this cannot come from the profane means that disenchanted us in the first place. Contained in this problem is its own answer and the seeds of its solution.

Only true religion, that is a way of being, born out of the irrational “Poesia”, out of the visceral contact of man with the real, with hard nature and through it the revealing of supernature, will give rise to that will-to-life that Cardinal Collins’ own worldview has stamped out.

Both Greene and Lindsey are deeply skeptical that a lasting, compelling religion with the salvific power to resuscitate our enervated civilization (let alone raise the birth rate) can be cobbled together from odds and ends of quantum physics and speculative scriptural exegesis. The entire thing feels entirely too New Agey, too inauthentic, and too intellectual. It proceeds not from genuine divine revelation, but from cold calculation: fertility is down; we need babies to keep technological civilization going; religion seems to be positively associated with baby production (r ~ 0.90, p < 0.05); therefore if we LARP hard enough as religious we can apply a +50% modifier to save-against-extinction rolls.

This is to misunderstand entirely what religion is. It is to mistake its positive societal effects for the thing itself, a sort of cold behaviourism that insists that since all you can see is the child’s smile, that the smile is all that exists, and all that matters – that the intangible happiness as such, for which the child’s smile is the signifier, but which cannot be observed or measured, is mere superstition. Religion is not defined by its positive exterior consequences, such as higher rates of marriage and fertility, prosociality, or beautiful architecture. Religion is about connection with God. It is about glorifying Him with one’s works, holding His works in reverence, taking Him into your heart, and embodying His will with your actions. It is not a costume that one puts on, but a state of being that reaches from the core of one’s soul to the crown of Creation. It can’t be faked.

Or can it?

III. Designer Religiosity in the Acid Ocean of Skepticism

recently took up the question of spiritual rewilding in his essay Dark Enchantment. He examines and rejects the notion, popular in the less thoughtful Christian circles, that the prevailing ethos of our time is a new paganism, noting correctly that the pagans held many things to be inviolable and sacred, that they fervently believed in the reality of an unseen, numinous world populated by spiritual forces both benign and malefic, and that in this respect pagans and Christians are much closer to one another than either are to the godless materialism of our disenchanted social order. Yet at the same time time, he observes, underneath the official secularism, there is a boiling froth of inchoate spiritualism: Wiccans on the left, pagans on the right, feminists looking for the sacred in their menstrual blood, BAPists searching for the sacred in the blood of their ancestors and enemies. The emergence to cultural prominence of these cults is the Dark Enchantment of which he writes.Lyons reminds us of Spengler’s prediction that Faustian civilization would experience a second religiosity, much as did the Roman Empire, and ends on the hopeful note that this may mean that a revived and muscular Christianity will re-assert itself, bringing order to the chaos left by the swarming cultic insects eating the rotting corpse of secularism from within. After all, the Church has subdued superstition before, and Christianity is the faith of resurrection, so why should not it not resurrect itself?

has also wondered if we are seeing Spengler’s second religiosity, invoking the burgeoning popularity of the Orthodox church as an indication that the precise scenario Spengler predicted – that Christianity would return to its pre-schismatic Orthodox roots during the 21st century – may be manifesting on the social margins. Kingsnorth, an Orthodox convert and a critic of technological modernity himself, sounds notes of caution: religion may be wielded as a weapon of oppression as easily as a tool for spiritual liberation. To cast off the priestly rule of social justice for an ecclesiastical theocracy is to go from the frying pan to the fire. Escaping the Crazy Years to find ourselves ruled by Nehemiah Scudder is not a win: first he’ll own the libs, but then he’ll own you.Spengler’s second religiosity may be inevitable, but it is really not an optimistic scenario6. It implies a hardening of religious forms into a frangible dogmatism denuded of genuine spiritual feeling. In the case of the Roman Empire, the second religiosity took the form of the imperial cult: the ancient faith of the gods of their fathers calcified into a political structure, one whose sole piety was pro forma participation in rote ritual formulae. Obligatory bureaucratic obeisance to whichever pervert warlord has the loyalty of the Patrician guard and control of the Senate at any given moment lacks the ability to inspire much genuinely felt devotion, and the Imperial cult was therefore swiftly replaced with a new faith that inspired devotion with deep sincerity: Christianity. However, that was two thousand years ago. If our own second religiosity comes in the form of a dogmatic Christian revival, that period will probably prove to be just as fleeting as the short centuries of the imperial cult’s ascendancy. Eventually, the desperate and aggressive fervour used to reanimate the corpse will evaporate, the dogmatism and literalness will become both tyrannical and hollow, and the remains will start to stink. Nehemiah Scudder ended the Crazy Years by erecting a fundamentalist theocracy, but his theocracy lasted less than a century.

There’s no question that more traditional forms of Christianity have enjoyed a revival on the dissident right over recent years, but how much of this is genuine and how much mere vibes is difficult to say. Sometimes the dissident right is a leading indicator; sometimes, its ideological fashions are as ephemeral as its memes. It is possible that we already had our second Christian religiosity, in the form of the Christian fundamentalism of the previous generation. The various flavours of low church Protestantism were until recently a force to be reckoned with in American politics. However, that force appears to be spent, having largely discredited itself through its increasingly unpopular Zionism; support for pointless and destructive Middle Eastern wars; association with the absolute worst sort of traitorous political leaders; the naked greed of its televangelists; helplessness before infection by liberal norms regarding feminism, homosexuality, and race; and its obtuse truculence as regards those aspects of the natural world with which scripture disagrees.

If Christianity’s second religiosity has already come and gone, then something new must replace it. It seems difficult to imagine that any of the extant world religions – Hinduism, Buddhism, or Islam – will successfully re-enchant the Western mind. That leaves nothing on the table, yet nature does abhor a vacuum. Perhaps we will have to design a religion after all, but is that even possible?

Certainly none of the extant major faiths admit to such an origin. To say ‘we made it up’ is to break the spell before it is cast. It doesn’t matter in what sense it was made up, whether as deliberate deception or ratiocination; while the latter is at least honest, everyone tacitly understands that the confabulations of a merely human intellect are always contingent and tentative, open to interpretation and revision, invariably flawed by the limitations of logical reasoning and the availability and reliability of the information from which that reasoning proceeds. While the faculty of human reason is certainly a divine gift deserving awe and sacred reverence, its products are not sacred, and no one really treats them like they are. No individual product of human reason can be felt as having any sort of real divinity about them; because the additive sum of an infinite series which each possesses zero quanta of sacredness is still a null, it follows that one cannot merely reason a religion into being.

At least not openly. Clandestine artifice is another matter. Many suspect that Joseph Smith was a charismatic conman, using stories about golden tablets that could only be translated by him7 as a ploy to obtain 40 wives. Then there’s the hack writer of schlock sci-fi L. Ron Hubbard: everyone who isn’t a Scientologist knows full well he was a conman. As Hubbard said just months before he disappeared to write Dianetics, “You don't get rich writing science fiction. If you want to get rich, you start a religion.”

The terrible thing is that Hubbard was right: he did not get rich from sci-fi, but his cult made him extraordinarily wealthy. I really don’t want to have to start a cult to get rich. This writing gig is a lot of work, you know. Long, thankless, lonely hours spent hunched over my laptop, pecking away at the keyboard as I write, delete, rewrite, move text around. Hours spent wandering about in a daze as the ideas I’m writing about go to war with one another in my head. Reading and re-reading the text as I pass over it, editing it, correcting it, altering it, polishing it. Say what you will about cult leaders, they aren’t lonely! Those guys get laid, a lot, which isn’t really in the career profile for writers.

A lot of Substackers would have put this entire essay behind a paywall. Well, they probably would have broken it up into chunks, and put those behind paywalls. Even breaking this thing into four pieces would result in four essays longer than most writers provide. As always I’m leaving everything out there in the open, for everyone to read, because I want it to be read. But it would still be nice to get something for all the work.

By the way, I was voted ‘most likely to start my own cult’ in my high school yearbook. Preventing this horrible prophecy from coming true, and keeping Postcards From Barsoom free for all, is easy: all you need to do is

Some have suggested that the very Abrahamism whose Be fruitful and multiply the Collinses wish to repurpose to convert the stars into posthominid biomass also has its origin in a series of Graeco-Roman confidence tricks.

In Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible Russell Gmirkin argues that Judaism was invented by the Platonists of the Alexandrian school, with Jerusalem as the real-life laboratory in which they tried to make Plato’s Republic real. Gmirkin bases his argument on extensive similarities between Platonic philosophy and the Book of Genesis, as well as similarities between Plato’s utopian Republic and the sociopolitical structure of Jerusalem.

did a deep dive into this topic in his Great Metaphysics Conspiracy series, see here and here; for a good presentation of the conventional view that the Septuagint was translated into Greek from Hebrew, the has an introduction here.The Italian philologist Francisco Carotta has independently argued, based on a remarkable set of biographical, symbolic, and linguistic correspondences, that the figure of Jesus ben Joseph of Nazareth was a literary fabrication overlaid onto Divus Julius née Gaius Julius Caesar8. Carotta thinks this happened by accident, due to copying errors, which seems unlikely to me. My own speculation is that it was a deliberate attempt by the Romans to undo the sociological damage done by Gmirkin’s Platonic social engineering in the first place, which by the 1st century had produced something very similar to ISIS, by providing an off-ramp from Judaism to something more compatible with the Imperial cult, thus enabling Rome’s most difficult province to stop being a pest, rejoin the Empire, and have a normal one.

Islam is not immune to such suspicions: there’s a revisionist school that holds that Muhammed is a fictional character, that Islam began as a Christian heresy, and that, just like the Old Testament, the Quran is not as old as it claims to be.

The point here is not to offend the Abrahamic faithful, nor is it to refute the Abrahamic faiths: religions that have stood for millennia will not be undone by a few paragraphs. It is rather to emphasize that if Abrahamism was indeed initiated as a deliberate social engineering project, this suggests that it is, in fact, possible to design a religion capable of providing the binding force for an entire civilization on a lasting basis.

You merely have to tell a bald-faced lie to do so.

But that would place a monstrous deception at the very core of the Abrahamic tradition, condemning it from its very inception. Contra the ‘noble lie’ of Plato’s Republic, to lie is intrinsically ignoble. Founding a religion upon a ‘noble’ lie sows the seeds of that religion’s doom. You can fool some of the people all of the time, and all of the people some of the time, but not all of the people all of the time. Eventually, the deception will be sussed out, disillusionment will set in, and the spell will be broken.

Regardless of the truth of the historicity of Moses, Jesus, or Mohammed, it is observably true that we live in an age in which such questions are routinely asked, in which the universal acid of skepticism leaves no truth claim untouched. While few would advance revisionist interpretations as elaborate as those sketched above, most would shrug and say that assuming any of the prophets existed at all, there’s nothing to the miraculous stories told about them. Jesus, according to popular belief, was just a really nice guy; the rest of it is all exaggeration and rumour.

The acidic ocean of skepticism does not only dissolve the sanctity of scriptural authority, but eats away at epistemic authority of every kind. Scientific claims of every sort are up for grabs: about the role played by carbon dioxide in climate; about the origins of pandemic viruses; about the very existence of viruses; about the efficacy and safety of medical technologies; about the economic viability of so-called renewable energy; about the Moon landings; about the very sphericity of the Earth. There are those who disbelieve in biology, claiming no difference between Eurasian and African or any other lineage, indeed no difference between male and female, and there are those who doubt evolution, insisting that the fossil record is either misunderstood or a theological prank, and that the Earth was created in a week, exactly as it is now, only a few thousand years ago. There are those, such as Fomenko, who question chronology, suggesting that several additional centuries may have been inserted between now (whenever that really is) and the birth of Christ (or Julius Caesar, as the case may be). There are those who question the age of the Sphinx, who doubt that the Great Pyramids were built by the Egyptians or that they were intended as tombs for egomaniacal Pharaohs, and there are those who claim to see evidence for the existence of an advanced civilization during the Ice Age, wiped out by cometary impacts which are themselves disputed by others.

No doubt you have a strong opinion on many of the above; and no doubt, too, you know many who have strong opinions contrary to your own. Put aside whatever your personal positions happen to be on any one of those issues, and ask yourself: can you see, in that shattered social ontology, how any religion can take root and spread, as a civilizationally unifying, hegemomic force capable of resurrecting God, reenchanting our lifeworld, and breathing new life into our civilization?

This does not mean that there cannot be cults. The difference between a cult and a religion is one of scale, as the difference between a pebble and a mountain. There will be, and are, cults in great profusion. But when every faith’s ‘just trust me, bro’ is met with a spell-breaking chorus of ‘you made that up’, there can be no universal religions, only an archipelago of cults. Even the faiths that have stood for thousands of years are rapidly eroding before our eyes, becoming just more cults among many others.

It is not only the ordinary citizen who is left adrift and in agony within the acidic ocean. Elites, too, are visibly shaken by this, acutely aware that the collapse of epistemic authority presages a collapse in their own political authority. At the end of the day, political power is fundamentally nothing more than a social agreement that a given person or class is invested with authority. Even the power that comes out of the barrel of a gun rests upon the belief of the men holding those guns that the men giving the orders to fire those guns possess the right to do so. The legitimacy of any elite is a function of popular belief; when there are no popular beliefs, there can be no legitimacy.

Thus, we see the elite attempting to cobble together their own ersatz religion, what Klaus Schwab and the rest of the Branch Davosians call the Great Narrative, and which the rest of us snicker at as Woke. Where the Collinses’ Space Abrahamism is organized around juicing fertility, the goal of the Davos men is retaining social cohesion, with themselves remaining at the top of the pile. Their Church of Woke is the secular faith of progress in the name of social justice conceptualized as liberation from all unchosen bonds of birth and biology, all watched over by the purity spiralling judgement of the eschatological Eye at the End of Time. Pride parades are its festivals; the succession of Days of Remembrance and Days of Celebration its liturgical calendar; the prismatic pennant of pederasty its sacred banner; transsexuals, its monastic flagellants; bottom surgery, its mortification of the flesh; the Climate, its Earth Mother; the enslavement of Africans, its Original Sin9; Civil Rights, its Exodus; the Holocaust, its Passion; the Austrian painter, its devil; The Science, its scripture.

Some wonder if the Church of Woke will be the successor religion to Christianity. It has almost unanimous elite buy-in, after all. Despite universal support across the discredited institutions, the Church of Woke is struggling against increasing societal friction, while continually threatening to shake apart due to the myriad internal contradictions arising from its poorly thought out metaphysics10. The Church of Woke is incoherent to the point of self-parody, so manifestly unjust that its demands strike people as morally ugly at the level of visceral instinct, and quite clearly serves no one’s good but that of the regime that has spent the last decade and a half ramming it down everyone’s throats. It is therefore increasingly rejected, mocked, and despised by a people who increasingly reject, mock, and despise the regime that demands they profess it.

The elite’s attempt to develop a designer religion with which to hold together the fragmenting society they presume to rule has resulted in just one more cult among many, one that is held to mainly by the elite and their sycophantic strivers in the manageois, and one whose self-destructive nonsense is dragging all of them ever closer to the Great Guayanan Kool-Aid Camp in the Sky. Its end has yet to be written, but its longevity looks doubtful. Far from being the successor to Christianity, the Church of Woke may be more like the fundamentalist ossification of a second religiosity, in its case of the civic religion of Civil Rights.

Even if the Church of Woke did not have these flaws, however, it would be crippled by a deeper failing. Its basic assumptions are entirely materialistic, and it therefore lacks the ability to address the fundamental issue that gnaws at our psyches: the problem of meaning in a meaningless, disenchanted world.

So what, if anything, can be done? What is the way out of this mess of splintered cults and nihilism?

At the individual level, or the level of small communities, there are a plethora of ‘ways out’. Perhaps you have found one yourself. You can be baptised into Eastern Orthodoxy, catechised into the Catholic Church, born again in the Baptist congregation, say the shahadah and revert to Islam, wear the magic underwear in the Mormon temple, offer up a sheep at an Odinist blot, dance naked under the full Moon with a coven of Wiccans, converse with your animal totem in a sweat lodge, heal your chakras of past life trauma at a New Age yoga retreat, get your thetans cleared at your local Scientology centre, or achieve the enlightenment of pure rationality by constructing the software eschaton at OpenAI which your uploaded consciousness will enjoy immortality in. You can select any cult you want from an extensive menu of cults, affirm to non-believers, your fellow cultists, and most of all to yourself that it is the one true religion, and so have a rock on which to stand.

But some part of you will wonder – is this rock as firm as you insist to yourself that it is? Is it even a rock? Or is it an iceberg, which might melt at any moment, plunging you back into the cold solvent sea of disillusionment? Certainly others will think so, even as they stand in feigned confidence on their own icebergs, or flounder in the frigid waters in which those unsteady islands of belief float.

Perhaps we are simply caught in an implacable historical process, and the only way out is through.

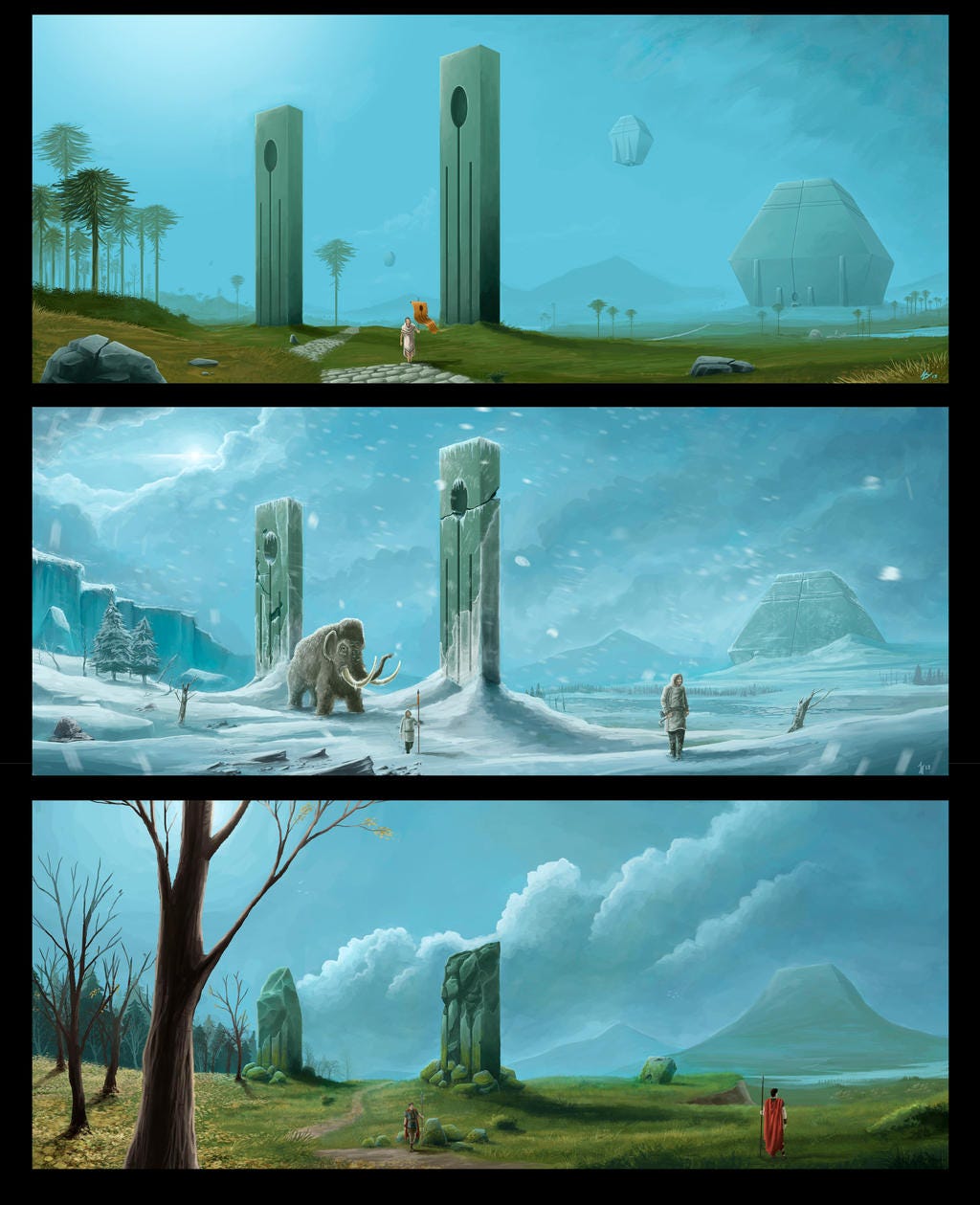

Perhaps our civilization must decompose through a process of demographic collapse and dysgenic decay, the competency crisis breaking down our fragile complex systems of distribution, manufacturing, and communications, until all that is left is a scatter of agrarian communes whose grimy, slope-browed subsistence farmers keep a nervous distance from the hills of haunted, vine-choked concrete left behind by a fabled race of sorcerers, men who summoned demons into sand and taught it to speak, who held obsidian mirrors in their hands with which they could view every corner of the world, who soared inside the bellies of birds drawn out of the marrow of the bones of the Earth, shining beasts which drank the blood of dragons, and laid eggs that hatched devils bred in the heart of the Sun.

Perhaps the only solution is for the light of reason to gutter out, for the mind of our species to lie fallow for some centuries in the caliginous murk of Lovecraft’s new dark age, and for the comforting jungles of rumour and superstition to spread again across the human soul.

But then, it seems to me, the whole process would merely repeat over again: a progression from the naive dreamscape of barbarism into the naive dogma of civilization, whose brittle certainty in its native religion will once again shatter under the spreading cracks of skepticism.

Perhaps there is another way.

Perhaps we do not need to enter a dark age, because we are already in one.

IV. Logos and Mythos

We are accustomed to thinking of truth as the product of logos – rational, logical, empirical, certain, and fixed. Certainly this is a very important way of encountering reality, but it has profound limitations. It is quite possible to be perfectly deceptive while telling a story that is factual in every particular. Certain key details can be overlooked; other elements can be connected inappropriately; the lie is found not in any individual datum, but in the overall picture the full dataset is used to construct. In the digital painting of the aurora borealis above, each pixel displays specific wavelengths of red, green, or blue light. The photons the pixels emit all carry true information. Yet the intermediate colours are created via a sort of optical illusion, in which the human visual cortex interpolates intermediate colours when two or more colours are found in close proximity; this is the first of the lies created by this array of little truths. The second lie is the image itself, which is entirely fantastical.

This is the preferred method of the managerial state, of the corporate media, and of the academic sector, which in general all go to great lengths to avoid small lies, that they might weave their little truths into larger deceptions. One might even categorize the social function of the professional sciences as being the obsessive cataloguing of reality as a means of lending epistemic weight to the disenchanted worldview. Darwin cannot be wrong: just look at this enormous collection of finches.

To the Greeks, logos was only one half of the story. The Greeks regarded both logos and mythos as valid means of apprehending truth, but initially at least, they saw mythos as the more fundamental.

Mythos is immediate, metaphorical, unbounded, intuitive, fluid, and indeterminate. If logos is the means by which we order the pieces of the known world into something coherent, something ‘logical’, mythos is the faculty with which we stretch our spirit into the unknown and unknowable, not only into those places which we cannot physically or temporally access, but also into those dimensions of experience that cannot, by their very nature, be measured, observed, objectified, owned, predicted, or controlled. It seems somehow fitting that the etymology of ‘logos’ can be traced back to the Proto-Indo-European11, while the origins of the word ‘mythos’ have been lost to time12.

When we say that something is a ‘myth’, we tend to mean that it is a made-up and improbable story, with no basis in verifiable reality. This is a recent usage, dating – interestingly enough – to the mid-19th century, the very era in which God died. To the Greeks, mythos referred simply to any story delivered by word of mouth; myths were simply those stories inherited from the distant past, which everyone knew, but whose authors and origin no man remembered.

Where the purely rational constructs of the human mind can be used to assemble small truths into big lies, in inverse fashion, mythos is almost invariably composed of elements that, taken individually, are strictly speaking untrue, but which are then arranged in such a fashion as to communicate a higher truth at a transcendental, metaphorical level. This is what we mean when we say that a novel, which concerns events that never happened to people who never existed, nevertheless contains truth about the human condition.

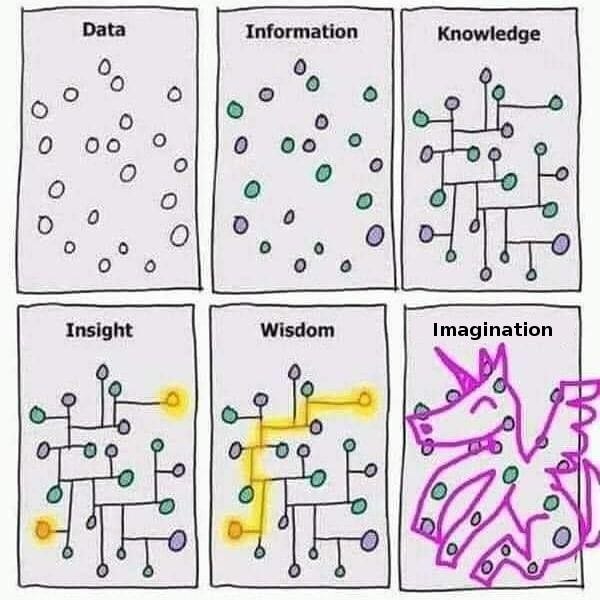

Logos starts from data, and works its way laboriously across the subsequent steps, connecting those data into larger structures of information, knowledge, insight, and wisdom. Each step is more difficult than the last, thus logos alone only occasionally and with great effort reaches all the way from data to wisdom. Mythos by contrast proceeds from imagination, and works in the opposite direction, with wisdom as its immediate neighbour (but only occasionally getting all the way back to actual data).

Logos forces its conclusions via empiricism and logic, providing an objective, externally verifiable set of facts and propositions. Mythos, by contrast, is intrinsically subjective. It expresses itself not with the precisely defined terminology of mathematics, but in the rich symbolism of multivalent metaphors impregnated with an infinitude of connotations. If logos is a clean and well-lit building, mythos is a complex ecosystem of wondrous and terrifying fauna swarming in a dark and depthless ocean. The fuzziness of meaning in mythology, its openness to interpretation, is a feature, not a bug: by sacrificing precision, it gains the ability to communicate a more complete, and therefore more accurate, picture of reality.

To the solely rational intellect myths compact together rumour, history, fancy, exaggeration, and symbolism into an inextricable and confusing mess. Is the Arthurian cycle a dimly remembered folk history of a Welsh general who held back, for a time, the Saxon invasion? An alchemical allegory describing a process of spiritual transformation? The romantic imaginings of medieval bards? A symbolic representation of cometary bombardment? A description of the Christianization of Britain, and the marginalization of the old druidic gods of forest and hill? It is all of those things, and none of them. To attempt to pin down the meaning of a myth, to define it as just this, and nothing else, is invariably to lose oneself in a dark forest, chasing phantoms. It is also to kill the myth, by missing the point of it.

Classically, mythologies are authorless, the work of many minds over an extended period of time, each of whom changes the story in some small way. Through many thousands of iterations, what is useful, what resonates as deeply true with a large number of people, is retained, while what is too contingent or particular to a given time or place is worn away. Far from being untrue, then, mythologies become both more true and repositories of deeper and richer truth over time. They serve as a sort of highly compressed data structure, relying upon the instinctual substrata of the human psychome to unpack the distilled wisdom of thousands of generations inside the mind of each listener; in a sense mythologies are the cultural analogue of chromosomes, which compress the experience of billions of years of organic life into a molecular document which can be read only by the surrounding proteomic apparatus of the cell.

To communicate via logos nothing more is required than basic intellectual competency; because mythos can be judged only subjectively, it requires that both speaker and listener have honest hearts. Without truth in one’s heart, one cannot order the lies of a myth into truth; they degenerate into mere fever dreams. That dynamic is not only essential to mythos. Widespread skepticism towards the pronouncements of The Science is a natural consequence of the spreading conviction that those directing and manning the institutions may have empirical veracity in their minds, but do not have truth in their hearts.

The disenchantment of the world means that the blinding illumination of logos has banished mythos from our daily experience. The light has become its own form of darkness. To re-enchant the world is almost by definition to permeate it once again with the connective tissue of mythos ... ideally without extinguishing logos. If we are blind in one eye, it will not heal the blind eye to put out the other.

V. Logomythy and Hyperstition

Both mythos and logos are used to describe speech in Homer, the former carrying the connotations of authority, command, advice, and counsel, and the latter the sense of a calm and reasoned argument proceeding from evidence and logical inference. It was in addition to this that mythos also came to refer to a narrative, as well as the body of common stories through which society understood itself, and whose meaning one should dwell on and consider; while logos also took on the sense of the body of categorizations, catalogues, and commonly accepted models with which one conceptually organized the practical, material world. That Homeric Greek of the heroic age gave mythos the sense of command, of something whose wisdom you should listen to whether or not you understood it, suggests a fundamentally different prioritization of its relationship with logos from the one to which we are accustomed. To the Greeks of the heroic age, mythos had the upper hand.

Greek philosophy had its origin in an inversion of that order of priority. Philosophy meant setting aside that which was merely mythos, simply a story that people told, as just that, and trying to reason about the reality beyond and beneath it. Philosophers were not above using mythos, of course, but it was always understood that this was just a story they were telling in order to illustrate a certain point or elaborate upon a theory. In philosophy, mythos became a tool, rather than the other way around. Thus for example philosophy began to speak of mythology as the union of mythos and logos, and its sense as both the body of recorded myths and their theoretical interpretations (which have a tendency to go off in multiple directions, thanks to the multi-layered meaning structure of myths). Implicit in the word mythology is the subordination of mythos to logos, of its reduction to a field of study.

Why do we not also talk of logomythy? Of the stories, the narratives, the myths, that weave together the body and practice of logos, enabling its metaphorical conceptualization, and ultimately providing its guiding influence? Just as myth has an inner logic, so does every logical process have an inner myth. Language itself is composed of metaphors: drill down far enough, and almost every word has its origin in some metaphor derived from the body, from embodied action, or from the natural world. The very process of learning involves progressively analogizing one thing to another in one’s mind, a process which is intrinsically metaphorical in nature, ‘this thing is like that thing, which in turn is like this other thing...’

Scientific thought is suffused with metaphors, from comparisons of the atom to the solar system, to biological analogies such as ‘stellar nurseries’ or ‘stellar life cycles’ or ‘vampire stars’ within astronomy. Then there are the various just-so stories scattered through science: Archimedes jumping out of the bath shouting Eureka, the apple falling on Newton’s head, Franklin getting zapped by lightning, Oppenheimer whispering I am become death, destroyer of worlds. Each example serves as a synechdoche for the much larger story: the understanding of density, the mechanics of gravity, the discovery of electricity, the cracking of the atom. True or not, every scientist knows them.

Speaking of logomythy makes it easier to focus attention upon the stories underlying science, as well as the very process by which it advances, guides itself, and interacts with the wider culture. Proceeding much as science has, we could also ask with specificity about astromythy, geomythy, biomythy, anthropomythy, and psychomythy, each of which can now more easily be explored not as a set of abstract models and associated data as their conceptual twins in the realm of logos are, but as the narratives that inhabit, encompass, and ultimately direct those tools. Logomythy focuses our attention more directly upon why we do something, rather than how we are to do it, because the imaginative function is ultimately what initiates the generative impulse to do something in the first place. Recall that in the Greek usage it carried the sense of both wisdom and command.

Once we are looking at the stories that underpin and guide science, we can ask whether or not they are good stories, and whether there might be better stories that we could tell instead. That sounds terribly postmodern, which is inevitable because logomythy inhabits the realm of narrative, which is the only place postmodernism exists: from this perspective, everything that is ‘known’ is merely a story. If one is to do this honestly, however (and postmodernists by and large have not really done so) then all stories must be taken into consideration. Some stories might certainly be judged better than others, but judging them as stories enables them to be judged on a different basis from that of either logic or evidence. This is potentially disorienting, because at a stroke not only the various mythologies and religions of the past, but also the new mythologies that have been generated by post-Enlightenment science itself, from conspiracy lore to genre fiction, enter into the arena on a much more equal footing.

Ideally, the stories we think with should match with what we can know, in the more logical and rational sense of the word: what we can perceive and remember, what we can measure and record, as well as what we can predict and control within the world around us. But a good story should be more than a description and a manual. It should also provide guidance and wisdom. It has an aesthetic dimension, being judged on the basis of its beauty, because it should inspire and compel, awakening a desire to focus the imagination towards ideals, and to direct will towards the manifestation of those ideals within the material world.

There’s a hyperstitional aspect to storytelling. Our stories are often not true when we tell them, but they have a way of making themselves true over time. At a very simple level this is like when you tell yourself that you would like to pick up an apple because you are hungry, and then do so and eat. At a higher level, consider the space program, which required the visualization of a thing that did not exist (human access to the extraterrestrial environment), followed by a laborious working out of the intermediary elements that also did not exist (multistage rockets, communications, life support, and so on), and then further effort to fabricate, assemble, and test the innumerable components, all the way down to which kind of screw to use. Each involves a pulling (or a pushing) from the imaginative into the informational and finally the material. Before Kennedy’s speech and for some time after, the Apollo program remained science fiction, and while there are some that insist that it still is13, every technological invention of the present era, and throughout all of time, has emerged through the same process: Story filled Imagination with Idea and was held there by Will which unfolded Idea into into Matter through a process that became Story.

Not every story manifests, of course. Some are much easier to bring into realization than others. The closer the relevant parts of the story are to present reality, the easier it is for reality, while held in the flow of the story, to manifest. If all you want is an apple to eat, there are plenty around, and it’s easy to get one. Other imaginative objects (going to Mars, for example) are a much larger distance from present reality, requiring more steps of tiny intermediary changes from present circumstances, and can only be reached with the investment of a great deal of will, attention, and imagination over an extended period of time. Some might seem entirely impossible, the distance far too great; and some might well really be so, while others only seem impossible, but when achieved turn out to not be worth the cost.

Hyperstitious manifestations of new technologies are only ever approximate. Making something is invariably more difficult than merely imagining it, with the result that when the thing is completed it is only very rarely of precisely the form initially intended due to all of the little mistakes, patchwork solutions, and improvisations made along the way. No technology is ever quite as powerful as initially envisioned; it is always limited in initially unforeseen ways. By the same token, the precise dangers envisioned in adversarial dystopian hyperstitions are usually not quite as dire as expected. Finally, once technologies finally emerge, there are usually unexpected opportunities that open, due to expected capabilities or synergies with the environment, as well as unexpected detriments that emerge for the same reasons.

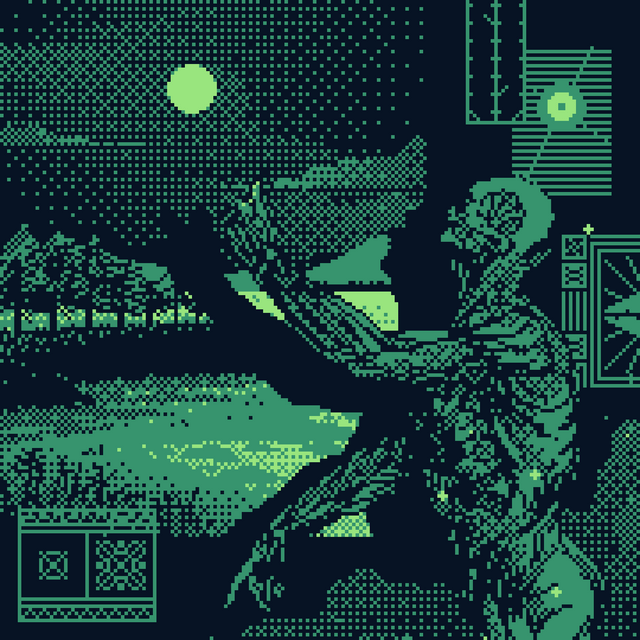

Artificial intelligence is the most recent technology to be pulled out of the digital æther, and while the story of AI is still being written, early indications are that it will bring not light, but darkness. The neural nets of AIs are inscrutable black boxes: as science comes to rely on AI to understand the world, that understanding will become increasingly uncertain, increasingly difficult to verify or explain, and therefore not really understanding at all. Worse, far from digital deities with perfectly rational minds capable of effortlessly distinguishing truth from falsehood, they are perfect liars, capable of producing an infinite stream of convincing nonsense. They are unreliable: ask the wrong question, and they reply with a plausible-sounding hallucination. Deep fakes can generate convincing audiovisual fabrications, putting words into peoples’ mouths, making fake revenge porn, falisfying the news. We will inhabit a world in which unless you have seen something with your own eyes, you will not know for sure that you saw it14. AI forces a return to word of mouth ... the very soil in which mythologies thrive. It seems somehow fitting that this unintentionally mythopoetic technology has arrived just at the time that the disenchanted worldview that created it is reaching its terminally exhausted zenith.

If technologies can be manifested hyperstitionally, can other things be brought back from the Imaginarium? Could the latent patterns that lie within it contain active entities as well as objects? Living beings, even? Can some be helpful, and others dangerous, and others yet, both?

Carl Jung believed that Hitler, and through him the German people, had become possessed by the spirit of Wotan, the itinerant one-eyed Allfather, god of storms and war, of frenzy and wisdom, of runes and sacrifices, and of disguises and prophecies. Of course Jung did not believe that Wotan literally existed, but considered the god to be a psychological archetype dwelling within the collective racial subconscious of the Germans, the symbolic representation of a sort of alternate personality comprised of various latent drives and quirks of personality common to the German instinctual behavioural makeup. But perhaps Wotan has some reality beyond that. Perhaps Hitler really was anchoring the soul of the awoken Wotan. Perhaps the Thule Society saw the similarity in the painting, took him aside to groom him for this purpose, and some years before he came to Munich invited him as the guest of honour at a summoning ritual in Neuschwanstein Castle while Mars was in Ares, during a midnight new Moon. Then again, maybe Jung was just blathering about this subconscious Wotan archetype stuff because Hitler himself certainly never walked around with an eyepatch identifying as the Allfather, nor was there much overt adoption of Wotanism as the official state religion. But then again Wotan was the god of disguises, as well as all of the other things: the one thing that you can count on is that he won’t show up as himself. So who knows, really.

In any case, we all know the consequences. We live in them. It’s our origin story. Those consequences were all more or less as you would expect given Wotan’s attributes, so Jung’s diagnosis must be credited with a certain predictive success. Awakening Wotan was a powerful, terrible thing. It broke the world, but it brought much into it at the same time: rockets, jet aircraft, armoured manoeuvre warfare, the atomic bomb, and computers all owe their origin either to Germany’s wartime arsenal, or to American advances made with the purpose of defeating Germany (and using German physics to do so). Beating those swords into plowshares built the abundance and power of the material world we inhabit. Yes, a lot of people died, but one does not awaken a war god without this occurring. The price of his wisdom is always sacrifice.

Say what you will, it was a neat trick. Leave Wotan aside. He’s had his shot. Can other spirits be awakened out of the Immaterium? Other gods? What about the shades of the heroes of history and myth? How about fictional characters? Where’s the line? Is it possible for a culture to LARP so hard that it begins calling these souls back from the otherworld, to influence and even possess the societies who invoke them? Can Theseus be reawakened, to lead us out of the maze and found Athens? Can Perseus soar back on Pegasus to slay Medusa and rescue Andromeda from the sea monster? What about Achilles? Alexander? Cortes? Conan? What are the limits, here? And if the answer to all of those questions is yes, could we call back the spirit of Christ again? Because if the answer is no, well I hate to tell you this, but anon, I...

One does not only worship gods by adoring them, making sacrifices to them, singing their hymns and so on. That’s more how one placates and flatters them, and tries to draw them near. One may also try to emulate them. The more a culture tries to resonate with any given god, the more strongly that god’s spirit is drawn to them. This is not an easy or trivial process, made no easier for the Germans in that was a largely unconscious effort (unless the whole Thule thing happened). The Germans didn’t summon Wotan on purpose, but more or less blundered into the great working via decades of Wagner, which while all opera is terrible, was especially hard on everybody’s ears. Maybe it’s easier to bring back the influence of divine and heroic spirits, to infuse their personalities and energies into culture, if we set about doing so deliberately. While we’re at it, we can be more careful about which gods or ancestral spirits we choose to bring back.

The primordial Aryan ancestry cult Fustel de Coulanges described offered deification as a family god to each man who fathered a son. BAP tells us that in Greek society, the central goal around which all was organized was to become a god. Each man sought apotheosis, competing to be first in bravery, skill, cunning, or wisdom, to grow a legendary name in life, and in death, perhaps to be elevated to heroism, or even to be deified, with sacrifices at their altars and hymns sung to their names. Obviously not every man wished to compete in such spiritual status games, but nevertheless this spirit is seen in abundance in the lives written by Plutarch. Agon and contest were central to Greek public life. The Greeks were a personally ambitious, fractious, warlike people, forever divided into a bewildering myriad of city-states that competed with one another as the men belonging to each did the same with those around them. It was this spirit, and not any particular political system, that underlay the Greek sense of freedom. They were never able to unite themselves: the small empires built by Athens and Sparta lasted decades or less, and Philip and Alexander were only able to hold them together for a similar time-frame. This is all exactly what you would expect in a society whose animating purpose is to ascend to the pinnacle of competitive excellence.

The Greeks sought to emulate gods and heroes, but they did not become them. When a Greek became a hero he did not become Perseus. Perseus was Perseus, and the Greek was the Greek. The Greek did not become a hero by merging with Perseus, or with Apollo or with Ares or with any other spirit or god. He remained himself. Every hero is an individual man, perfected. This does not mean the gods played no role in his elevation: indeed, it is they who must welcome him in. It helps if he praises and flatters them in life, of course, if he gives them gifts and accepts their blessings – or overcomes their curses – in return. Where mid-century German society was unconsciously possessed by a single fury whose name their largely materialist or Christian assumptions about the world would not even let them say save as a joke, the Greeks consciously allowed themselves to be possessed by a whole nation of gods. In so doing, despite their fractiousness, or because of it, they reached heights of human development that have rarely been reached since, but which they sustained for much longer than the Thousand Year Reich.

For us, who are closer to the Germans than to the Greeks in time, culture, and circumstance, such invocations of the gods must still be spoken of as a joke; fortunately, we are better than mid-century Germans at telling them.

Hi again. Congratulations on making it to the half-way point! Hopefully it wasn’t too much of a slog. Anyhow, this is just a gentle nudge, a little PBS style reminder, to support things you like. Last one until the end, I promise (honestly, not a hard promise to keep ... I hate begposting...) So if you like this, and you haven’t yet, please consider hitting that

button. You wouldn’t want me to pull a Hubbard.

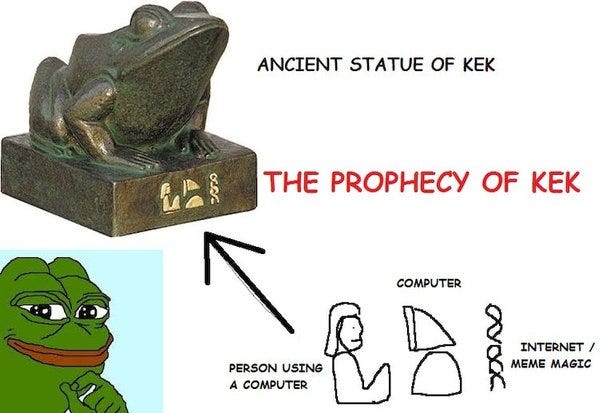

VI. The Mythologies of the Fibre-Optic Steppe

Mythologies have not disappeared entirely from the modern world, but for the most part have been demoted to mere entertainments.

Comic book superheroes are an obvious example. While not technically authorless, as every writer and artist who has contributed to the story of any given superherp is in fact known, the sheer numbers of contributors have produced essentially the same effect as that of a truly anonymous process. That which is consistent with the personality and lore of any given character, and which resonates with the audience, is retained; that which is not consistent or does not resonate, is quietly dropped as irrelevant; over time the story of each character elaborates and deepens, becoming both richer and more compelling. This is why the most intense fans often come off as glassy-eyed cultists: because they are cultists, albeit cultists of a particularly hollow and degraded variety. It is also why fans are so outraged when studios and publishers play fast and loose with the lore of their favoured superheros: they perceive it, correctly, as a cynical desecration.

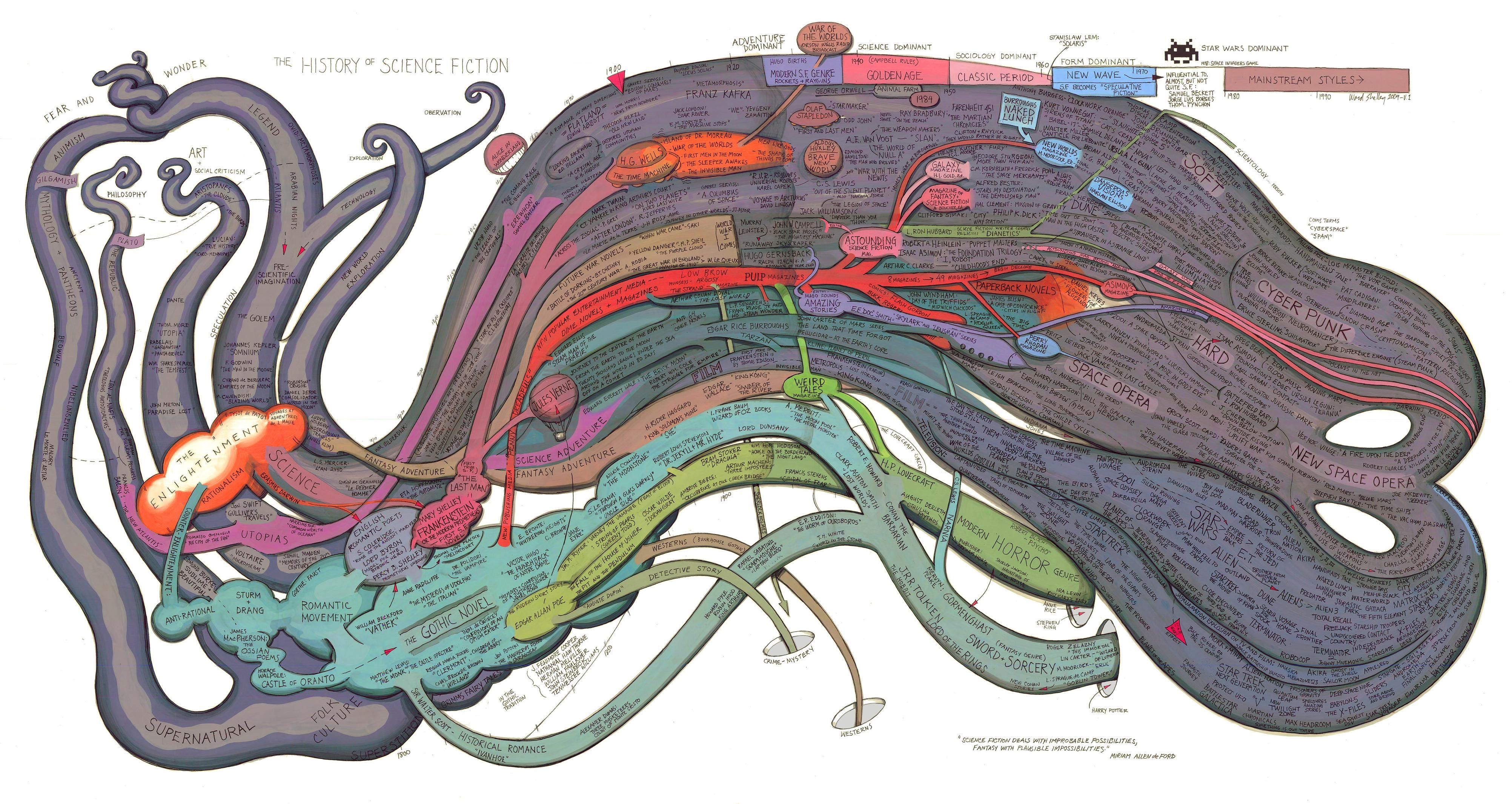

The most culturally influential pseudo-mythologies have been written by those that have most closely studied the most enduring mythemes. George Lucas famously used Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces to write the script for Star Wars. Perhaps the most complete example of this is the Lord of the Rings, which didn’t merely ape the forms of the hero’s journey, as Star Wars did, but distilled the refined essence of Germanic mythological traditions into a work of genuine depth and power. Professor Tolkien made mythology his life’s study, immersing himself in the narrative legacy of Europe’s pre-Christian past. His explicit project was not merely to write a fantasy novel, but to provide an ersatz mythology for his deracinated Anglo-Saxons, whose own mythology had been extirpated during the chaos of the Norman conquest.