V. Solutions to the Fertility Crisis

Forget carbon dioxide, nuclear war, bioengineered plagues, or rogue asteroids.

Depopulation is one of the most pressing existential threats to our civilization.

Fertility rates are in free-fall throughout the developed world. With current trends, our planet will become a global granny state – old, tired, and grey, with the shrinking population being crushed under a top-heavy demographic pyramid that diverts an increasing fraction of resources to the elderly. An older populace will be less innovative, creative, and energetic, meaning that culture, science, and technology will stagnate.

We live in the age of the behavioural SINK – a society dominated by the Single Income, No Kids demographic. The SINKs are predominant among the educated, intelligent, and technically adept. If they do not reproduce themselves – and by and large they are not – the cognitive traits that lie for the basis of our advanced civilization will be steadily bred out of the gene pool. Rather than ascending to conquer the heavens, humanity will putrefy in the mud, and regress into a new dark age.

In the first two chapters of this series, I explained the nature of the Depopulocalypse: what it is, why it matters, and the many factors driving it. In the third chapter, we looked at some of the solutions that have been tried, largely unsuccessfully, and then in chapter four considered some of the proposed solutions that, at least in my opinion, are unlikely to work: mass euthanization of the elderly in order to rebalance the population pyramid via demographic amputation; forced pregnancy via a theocratic state; and manufacturing humans to order in artificial womb factories.

Now, we’ll look at solutions that might actually work.

As we saw in part 2 with the example of Israel – the lone developed state with above-replacement fertility – while culture is extremely important, cultural factors alone are insufficient to reverse the trend. On the other hand, just throwing tax dollars at the problem does nothing to address the underlying reasons for the problem.

Ideally, we want a set of solutions that address the factors leading to a barren social womb in the first place. Even better if those solutions are fiscally neutral, or a net positive.

Let’s quickly recap those factors holding down fertility. In no particular order they are:

1) Obesity

2) Hormone-disrupting chemicals

3) Urbanization

4) Difficulty finding a spouse

5) High expense of housing and children

6) Long duration of education

7) Incompatibility of family and professional lives

8) Child-rearing being seen as low-status

So we need solutions that

A) Make it easy for people to get healthy, fit, and beautiful, and therefore both attractive and fertile

B) Rebalance urban and rural populations

C) Make it easier for people to find compatible spouses

D) Reduce the expense of housing

E) Ameliorate the trade-off between education and family formation

F) Reintegrate family and professional life

G) Raise the status of large families

Moreover, we want those solutions to be inexpensive, cost-neutral, or better yet even to generate wealth.

Some of the solutions proposed below are amenable to implementation by small groups or even individuals, but in general I’ve tried to focus on the big picture, because this is a macrosocial phenomenon. The premise is that these are the measures likely to work if implemented by a government that wants its population to grow via natural increase. The majority of them, I think, are at the full-society scale relatively inexpensive or even cost-neutral; some even generate wealth on their own.

If implemented at smaller, subcultural scales, the cost analysis is liable to be quite different, meaning in general ‘much more expensive’. There’s a big difference between the net cost incurred to society by redirecting the allocation of resources, versus the cost incurred to small groups attempting to appropriate resources from the wider society towards ends that society does not share, and is even hostile to. That said, many of these solutions don’t require state backing to implement directly, but could be adopted by subcultures. Others, however, by their very nature require the involvement of the heavy hand of state, if only in getting out of the way.

Solutions are divided into the following categories:

1. Propaganda

2. Courtship & Marriage

3. Women’s Education

4. Women’s Work

5. Diet & Agriculture

6. Physical Education

7. Plastics

8. Contraception

9. Village Life

10. Housing

11. Elder-care & Child-care

As can be inferred from the breadth of the subject matter, the measures proposed here, if implemented in toto, would comprehensively re-fashion society. I think, however, that the society that would result would be far more vital, life-affirming, and human for all its inhabitants, as compared to the cold machine we currently inhabit. The over-arching idea is to start with the human animal as it is, biologically, psychologically, socially, and spiritually, and organize society around that basis.

If our time is the drowning era of the SINK, the future, I hope, will belong to the FLOAT – the Fertile, Libidinous, Optimistic, Affluent Technologists. The FLOATs are the ones who have learned the trick of weaving the living current of vital energy that pulses through the soul of mankind into the weft of material wealth conferred by mastery of advanced technology; the ones who have learned to use technology not to deny life, but to enhance it, not as a shackle upon humanity but rather as an accentuation of humanity. The FLOATs are the ones who will turn the solar system into a garden.

So, let’s learn how to FLOAT.

1. Propaganda

This one comes first because culture is probably the single most important factor. None of the other interventions – biological and economic – count for anything, if people don’t want to have kids. Conversely, if they really want to have them, life will find a way.

The antinatal bias in modern entertainment media is blatant. The child-free life is celebrated, parenthood is depicted as a sort of prison, large families as low-status , early motherhood as a catastrophe.

It would be cost-neutral to reverse this, as either way money is being spent to make TV shows, movies, and so on, and it’s just a question of which get made. Instead of presenting fathers as clueless morons, show them as strong, wise, loving men trying to do the best they can, and usually succeeding. Hold up fatherhood as something young men should aspire to, rather than dread. Similarly, instead of showing mothers as depressive malcontents whose inner harlots are trapped by the fetters of family life, depict them as nurturing lionesses fiercely devoted to their children. Instead of writing ‘strong women’ as men with tits, show them as strong women – doing their best to embody the feminine virtues ... and if they’re single, focused on the ultimate prize of landing a good husband so that they can start a family.

Good propaganda should not be ham-fisted. We don’t need a censorship bureau demanding that family life always be shown as some kind of Leave It To Beaver utopia. That isn’t compelling, and no one will buy it. But it can be shown as something fundamentally positive. If you want an example of what I’m talking about, watch Avatar 2, and pay attention to how Jake Sully and his family are portrayed. It’s a masterclass in how to embed familial virtue in a kinetic plotline. On the surface the movie has nothing to do with family: it’s Dances With Aliens and Space Pocahontas running off to save the space whales alongside the Space Maori from Space Ahab. That Jake is shown as a strong, protective father; Neytiri as fiercely devoted mother; and their children (three of their own, one adopted, and one sort-of-adopted, for a final family size of five) as a tight-knit gang whose siblings rivalries never overpower their sibling loyalties, is there in the background. It drives the characters’ motivations but the movie never beats you over the head with it.

The idea here is simple: get young women to want to be young mothers, so that they’ll naturally gravitate to motherhood. And the same for young men, of course.

There’s no reason negative propaganda can’t be used as well. Childlessness can very easily be portrayed as selfish frivolity. Invert the current formula in which the nihilistic hedonism of the child-free life is celebrated, while family life is shown as the suffocating slayer of dreams.

Propaganda doesn’t only mean movies and TV shows, although these are by far the most effective. Memes, TikTok videos, novels, and music can all be used to celebrate parenthood. This essay is a form of propaganda. Even individual phrases can be – SINKs, for example, is particularly devastating. While using major studios to create and distribute high-production value content is the most valuable form of propaganda, there’s nothing stopping individual people or small groups from pushing out their own. As indeed some are already doing.

Propaganda is meant to point towards an ideal, which of necessity will never match actual conditions in reality. That’s the purpose of the imaginative function: to visualize where we want to go, either individually or as a society, while also warning against where we don’t want to go. But it can’t be too out of step with people’s everyday experience. Propaganda celebrating large families raised by young parents will fall flat if there’s no viable path to that life for most in the audience, and they’ll just tune it out as a result: one of the reasons anti-natal propaganda is so effective is that the material and social conditions of modern life conspire to make barren singledom the default fate. So while it is absolutely essential that the memes of reproduction be propagated into the culture, that alone is insufficient if the society itself is structurally set up to make it maximally difficult to have children, as it currently is.

Cost evaluation: on a macrosocial scale, basically zero since we’re spending money to make video entertainment anyhow. However, I doubt we’re going to get Hollywood on board with this in the near future. On a subcultural scale, the cost can be considerable – even a low-budget film can run to tens of millions of dollars, and if you want people to watch it in large numbers on Netflix you’re probably looking at a lot more than that. If Elon Musk is genuinely worried about this problem, and I believe he is, he’d be well-advised to devote a few billion to a pro-natal production studio. Other forms of propaganda are however extremely cheap – the marginal cost to make and distribute memes is zero.

2. Courtship & Marriage

The current model for romantic relationship formation is completely broken.

Only a few generations ago we had an intricate set of social technologies intended to streamline the process of pairing off the young: church dances, debutante balls, village matchmakers, courtship rituals in which it was explicitly understood that the end stage was marriage and children. The older generation went out of its way to provide avenues for the young to meet, while at the same time applying social pressure to pair off, and to do so at a relatively young age.

None of that exists anymore. The young are essentially told to figure it out themselves, and most are lost in a confusing and contradictory landscape of situationships, Tindergamy, one-night-stands, simping, porn, and night clubs. The boundaries between friends, friends-with-benefits, boyfriends and girlfriends, and spouses are fluid and uncertain. There are no clear guidelines on what differentiates a simple expression of romantic interest from sexual harassment. Ask a girl out, and you don’t know for sure that it’s even a date – maybe she just thinks of you as a friend, maybe she’s just using you for dinner. It’s possible to be with someone for a long time and not know whether or not you’re even in a relationship. People can live together for years in sterile cohabitation, extending the try-out period beyond any reasonable person’s emotional tolerance.

The whole thing is simply exhausting. Many give up, withdrawing into solitary pursuits. Others play the game for a while, only to get burned time and again, and find themselves jaded, bitter, and every bit as childless as the incels in their middle age.

If we’re going to raise the birthrate, we need to rethink how people meet.

One option is to revive matchmaking.

Matchmaking has advantages over the more casual dating method we’ve been relying upon for the last few generations. It takes the initiative out of the hands of the young: rather than waiting for them to get over their insecurities, it actively pushes them together. It leverages the copious free time of interfering old women, who have a great deal more time and energy to put into it than the busy young. It dramatically extends the pool of potential matches by drawing upon a wide network of social connections. Most importantly, matches tend to be made on a pragmatic rather than romantic basis: pairings are made not on the basis of what someone thinks they want, but on the basis of what their personalities and prospects actually are, and what those who know them best know will actually make them happy in the long term.

As it stands, it isn’t practical to return to the age of the village matchmaker. We don’t live in small, tight-knit communities anymore. However, we do possess digital social networks that span the globe, and these seem like they could be well-suited to building out a matchmaking infrastructure. For all that we have been atomized, most of us still have extended families which include older female relatives who know which members of their own immediate circle of family and friends are single; these older women usually have friends of their own, who have their own circle of family and friends, which invariably includes other young singles. Instead of posting their vacation pictures on Facebook and arguing about Trump and vaccines, or whatever it is that old ladies do on Facebook, they could spend at least some of their time working together to try and pair off their nieces, nephews, grandchildren, and so on with appropriate matches.

Another possibility is to look to the network itself. Matchmaking startup keeper.ai is hoping to do just that, by combining machine learning with human curation to pair off customers with their ideal matches. keeper.ai was designed by pro-natalists, and it isn’t about hookups, but about marriage and family. The goal of the startup is explicitly to be the anti-Tinder: rather than keeping people on the app indefinitely in order to soak them for small monthly payments as their souls shrivel and their STDs accumulate, keeper.ai only gets paid when a match is successfully made. Matches are pricey: it costs a few thousand dollars to see each match (or $250, depending on which article you read), although the company refunds if the match doesn’t result in a date.

It’s early days yet for keeper.ai: so far they only have about 1000 customers, which isn’t anywhere near enough to move the needle, and means the probability of finding a high-quality match for any given customer isn’t very high. Indeed, so far they have matched precisely one happy couple. Still, if something like keeper catches on, it could prove revolutionary. As the user-base expands the probability of good matches goes up dramatically, just on a statistical basis; furthermore, given the nature of machine learning technology, the more training data the AI can draw upon, the more effectively it will be able to identify good matches. Imagine a system with hundreds of millions of users, which has been trained up on not just whatever answers they give to their onboarding forms but also on, say, their social media histories, their DNA tests, and so on, and which has furthermore seen several years – ultimately, perhaps, several generations – of matches complete with followup data from divorce courts and birth certificates, and can therefore predict with high accuracy which matches are likely to result in marriage, how long those marriages will last, and even how many children will result. One could imagine a system which is capable of scanning through the world’s available hundreds of millions of singles, and finding the tastiest fish in the sea for all of them. This removes a lot of the mystery and adventure from romance, reducing it to little more than statistics ... but does that matter, if the result is happier people with larger families?

Another tactic to fight back against the tyranny of Tinder is to go radically low tech. An example of this is the pear ring. This is nothing more than a turquoise ring that indicates that the wearer is both single and open to being chatted up. The idea is to remove some of the uncertainty from in-person encounters. In the modern context, it isn’t at all uncommon to start talking to a girl, only for her to casually mention that she has a boyfriend half an hour into the conversation; since there’s no real way of telling who’s single and who isn’t, people often don’t even try to find out. Pear bills itself as a ‘social experiment’, but it’s really nothing fundamentally new. Many if not most societies have had some form of visual indication that an individual was on the sexual market. Before the sexual revolution destroyed marriage, our culture indicated this with a wedding band; in the past, a woman whose hair was free was understood to be single, while if she was married her hair was bound up or covered; in India, a married woman was traditionally known by her bindi, the little red dot on her forehead. Since married people don’t always wear rings anymore, and many couples eschew marriage and wedding rings altogether, Pear turns this on its head by suggesting that singles advertise their status.

The tactics suggested above are focused on getting people together in the first place, but however people are paired off, the next part of the problem is keeping them together. The contemporary dating system is open-ended and therefore highly unstable: relationships can last for hours or years and break apart with little or no warning. One possible answer to this is in replacing dating with time-bound commitments. In most traditional societies, courtship was understood to be a temporary phase with the permanent bond of marriage as the intentional end-point; with marriage destroyed, people often stay in the courtship phase indefinitely. Time-bound commitment is essentially training for marriage. At the beginning of the interaction, the couple agrees to stay together for a specific length of time – a week, a month, a year, whatever, that’s up to them. The point is that they start out by making a promise that they will stick with the other person exclusively for that period, with clearly defined expectations throughout. At the conclusion, they can either continue, or not. In a way this is similar to how formal dancing used to work: it was understood that a dance was a just a dance, and that at the end of the dance, if one of you didn’t want to keep dancing, then there were no hard feelings ... but if you both wanted to keep dancing, or escalate to something more, then possibilities might open up.

Cost evaluation: With the exception of matchmaking AIs, none of the solutions suggested here are particularly expensive at the macrosocial level.

3. Women’s Education

A human female’s fertility peaks between her late teens and late twenties, and falls off a cliff in her thirties. Her body assumes that she’s going to be making babies more or less as soon as she’s ready to do so, and further assumes that the younger she is, the stronger and more energetic she is, and therefore uses her best eggs first under the logic that the highest probability for survival is the combination of a child with minimal mutational load being raised by a young and vigorous mother. In keeping with this, a woman’s attractiveness is a strong function of her youth.

Ignoring these hard biological limits like a drunkard walking the wrong direction down a freeway, we instead put our young women into a professional educational system that was designed for young men back when women were a rarity in every college from which they weren’t simply banned. Men can quite happily spend their early twenties, or their entire twenties, or their early thirties for that matter, acquiring professional skills – male fertility does not decline nearly as rapidly as that of women, and through most of human history it was expected that a man would become established professionally, and therefore capable of supporting a family, before getting married. It is entirely reasonable to expect men to spend several years making very little money as they learn their vocations, and delaying family formation as they do so. It is not reasonable to expect the same of women.

One, rather heavy-handed, solution to this would be to simply ban women outright from colleges. Much as that appeals to my blackened miosgynistic heart, I doubt many people would go for it – women, in particular.

Instead, we need to re-think the educational careers of women. Instead of the norm being that they finish high school, go to university, and then, if particularly intellectually talented, go immediately into graduate or professional school, after which they spend some number of years working to establish themselves professionally, and only then having children (by which point, for many, it is too late), child-bearing should be more or less the first step. It should precede higher education, not follow it.

A biologically rational career path would look more like this: first child at 20; after that another child every year or two until the age of 26 or so, at which point 3 or 4 new lives have been brought into the world, and the oldest children are sufficiently mature to do a few chores and help mind the youngest children. At that point, if so inclined, a woman can embark on a program of higher education in order to pursue a career as a doctor, an accountant, a scientist, or whatever.

All of that assumes a conventional educational apparatus. Modern communications technology may offer a way to have our cake and eat it too. Asynchronous online education offers plenty of tools with which to educate oneself, at home, and on one’s own time. These could very easily be leveraged to enable young women to care for small children, while simultaneously pursing an education in whichever field interests them, with whatever practical element that cannot be performed remotely being undertaken at the end of her child-bearing phase.

Another thing worth pointing out is that while women have much shorter reproductive lives than men, they have longer lives. A woman who starts her professional career a few years later than a man might easily still have a career of equivalent length.

The main point is this: rather than requiring women to establish themselves professionally before reproducing, we should accommodate biology and enable them to reproduce before establishing themselves professionally. We should not ask them to fit their precious, irreplaceable child-bearing years to an educational schedule designed with men in mind. Biology is not flexible; social structures are.

Cost evaluation: whether women are educated early or late, the cost to do so is the same, so it looks pretty neutral to me. One might argue there’s an opportunity cost, since her professional career is starting a few years later than it might otherwise. That looks rather minor to me, however, especially when one considers that there’s an opportunity cost involved with having children in any case, which tend to be a drag on one’s professional life when they’re very young. Furthermore, if online tools are used to fit an education into her spare time in between minding the children, this almost certainly saves money, since online education is much cheaper than the traditional kind.

4. Women’s Work

Many trad-aspiring families with a pro-natal orientation aim for the 1950s era model in which the husband is the primary breadwinner and the wife stays home to look after the children. Supporting a full-time, stay-at-home mother on a single income is a daunting task for most men, especially given the economic realities of the Long Recession. Historically, however, it was almost never the case that all women did was sit in a chair nursing one baby while pregnant with the next ... idleness was a luxury available only to the wealthy, which was not most people.

As described in Part 1, we have completely misunderstood the nature of ‘woman’s work’. It has nothing to do with men having greater upper body strength than women, although this was certainly a relevant factor during the agricultural and industrial ages. It isn’t even primarily driven by the cognitive differences between object-oriented men and people-oriented women, although these play their role in occupational preferences. No, the most important discriminant between men’s and women’s work is this: traditionally, women’s work is everything that can be done with small children around; men’s work is everything that can’t.

The answer here is pretty straightforward: as much work as possible needs to be moved back into the home, and organized in such a fashion that it can be performed around the requirements of babies and small children.

In many ways, thankfully, we’re already on that path. The work-from-home revolution that’s devastating commercial property values in urban centres may well prove to be a godsend for fertility rates. A woman working remotely from a home office can quite easily generate income while looking after her children. Many remote jobs aren’t high time pressure in the sense that they require an immediate response: whether the report is filed now or in thirty minutes isn’t a matter of life and death, for example.

The main thing impeding work-from-home from being taken up more widely for jobs that can be done remotely is institutional inertia from employers. Large corporations in particular are reluctant to embrace this model, as managers tend to feel it’s easier to keep workers productive and on-task when they’re looking over their shoulders in the cubicle farm. There’s something to this: there’s a psychological effect of being surrounded by busy people that tends to help one focus on work, and anyone who works from home knows that it’s absolutely essential to have a dedicated work space in order to get into the work mindset. In any case, workers got a taste of work-from-home during the lockdowns, and they liked it: they’re as reluctant to return to every-day office commutes as employers are reluctant to let them work from home every day. So far that seems to be a losing battle for the employers. The state could help here simply by putting its thumb on the scale in favour of work-from-home, making full-time remote work a mandatory option in any contract involving administrative or intellectual labour.

Another area in which state power could be beneficial would be in easing zoning restrictions inhibiting commercial activity in residential areas, and in reducing the regulatory burden overall on small businesses. Historically, humans have not lived in vast suburban tracts in which the only thing you were allowed to do with your property was sit there and exist. Our work lives and our domestic lives have usually been intimately intertwined, for women especially. Insisting that commercial activity be kept geographically segregated from our living arrangements has resulted in “communities” where no one knows anyone, and Big Box megacentre parking lot wastelands where again, no one knows anyone. It’s isolating, alienating, inhuman, and ugly. By moving towards a mixed-use residential/commercial model, and in particular one that favours household enterprise, our communities will become actual communities again.

There’s probably an argument to be made that zoning restrictions were a big factor fuelling second-wave feminism. Bored housewives sitting at home with nothing to do become depressed and restive. Working in an office is obviously better – at least there are people there. So they began agitating to be allowed into previously male workplaces. Instead, make it much easier for women to work from home, whether online or off, and more women will choose to do so; rather than sitting alone in an otherwise empty house, perhaps trapped with a single crying infant for company, they’ll be in a proper community with other women, a place where they can walk down the street to get what they need, while feeling useful themselves by contributing economically to the community and to their own family, and comfortable letting their kids run around outside because each knows and trusts the other mothers to keep an eye on her kids just as she does on theirs.

Cost evaluation: Working from home might be a bit less efficient than working in an office, but then again it might not be, to say nothing of the money and time saved commuting. Overall I’d expect this to be pretty cost-neutral, and probably even save money, on both macrosocial and subcultural scales.

5. Diet & Agriculture

Seed oils have gotta go. There, I said it. They’ve just gotta be eliminated entirely. They’re a primary reason for the obesity crisis and are very probably hammering men’s sperm quality and reducing testosterone as well.

Note that I didn’t say something like ‘people should be encouraged to eat more healthily’. They should, but you can hector people about garden-fresh food or whatever all you want, if 90% of the cheap calories in the supermarket are derived from soybean and rapeseed oil, then that’s what people are going to eat. Hate Cass Sunstein all you want, I think the guy’s a creep too, but he’s entirely correct that if you want people to make good decisions the best way to do that is to make the good choices the default choices. In this case, that means arranging our agricultural economy in such a fashion that the foods most easily available to people aren’t mutagens that turn them into androgynous lard blobs.

Banning seed oils overnight would probably cause a famine. They’ll need to be phased out. My preference would be to simply yank the subsidies that are currently lavished on the industry, which would make most of it unprofitable overnight, and redirect that money to subsidize the cultivation of healthier substitutes – butter and lard, primarily, which were our primary sources of fats before seed oils were introduced. Much of the land currently given over to the cultivation of soybean, rapeseed, and corn is better suited to pasturing large ungulate herds, in any case ... with the additional advantage that grass-fed cattle are healthier than livestock raised on feedlots.

Devoting more land to livestock production, and less of it to vegetable oils, would reduce the caloric efficiency of land use. There’s no real question about that. But it isn’t a huge difference, only about a factor of two1, and the quality of those calories would be much higher. Humans raised on a diet rich in animal protein are taller, stronger, more energetic, more intelligent, and more beautiful than humans raised on seed oils. Source: just look around.

Seed oils are not the entirety of the dietary problem. Our industrial food system relies extensively on large-scale monocrop agriculture which is rendered into various processed food-stuffs, suffused by necessity with a witch’s brew of preservatives, emulsifiers, humectants, artificial flavours, and so on, with the ingredients themselves being laced with herbicides and pesticides, while being frequently deficient in vitamins and minerals due to being grown in soil depleted by heavy reliance on chemical fertilizers. In general, the better the soil in which it is grown, the fresher the food, the fewer the ingredients, and the fewer the industrial inputs, the healthier it tends to be. With all of that in mind, an agricultural policy that incentivizes regenerative agriculture and permaculture with an eye towards maximally localizing food production would go a long way towards making healthy food much more affordable. Of course, these methods are much more labour-intensive, but as I’ve argued before, if the AI revolution lives up to its billing we’re soon to have a surplus of unemployed office drones.

Cost evaluation: seed oils are cheap calories, so this will probably result in food being more expensive. On the other hand, eliminating the subsidies to big ag will probably save money. Overall I’d rate this intervention as moderately expensive at a macrosocial scale. On a subcultural scale, acquiring one’s food locally, organically, etc., and eschewing processed foods, is certain to make a dent in your budget.

6. Physical Education

The Spartans emphasized physical education for their women, because they understood that strong women bear strong warriors.

Removing seed oils from the national diet will help to raise people’s resting metabolic rate, making it easier for them to avoid obesity. But it’s still possible to get fat eating real food. Moreover, fit bodies are more energetic, more virile, and more beautiful – more likely to have strong sex drives, and more likely to be appealing to the opposite sex.

This one is actually a very easy fix. Right now ‘physical education’ in the school system is basically just a way to burn off some of the kids’ energy so that they’ll sit still as the midwit ed school certificate-holder plods through through the latest curricular innovations pushed out by the equally dull bureaucrats in the education department. Now that Adderall is available to hyperstimulate the neocortices of the more “hyperactive” – read “normally active” – boys, phys ed is an increasingly superfluous afterthought. Why waste time in gym class when they can learn all about the Tulsa massacre?

This view of phys ed misses the point entirely. The goal of physical education shouldn’t be a yard walk, as though the kids were convicts being let out of their cells for the minimum time necessary to avoid deep vein thrombosis. It should be athletic training, explicitly calibrated to tone and build their muscles, develop their cardiovascular systems, and tune their peripheral nervous systems to be graceful and coordinated. It shouldn’t be ‘fun’. It sure as hell shouldn’t be easy. It should hurt a bit. The kids should sweat. They should be exhausted afterwards. They should be spending at least an hour a day, and maybe two, working out. And by the end of high school, the modal teenager should look like an Arno Breker stature.

What’s more, it should absolutely not be optional. Most high school programs make gym class an elective, so of course only jocks take it. Universities don’t give a shit about what kind of physical condition you’re in unless you’re trying out for the college football team. You can very easily graduate with honours without once running a lap or laying eyes, let alone hands, on a barbell. To the contrary, physical achievement should be an absolute requirement to graduate high school. Body fat over 20%? Can’t bench your own weight? Can’t run a five minute mile? Sorry, no diploma for you. It goes without saying that similar curricular standards should be enforced at universities.

There is nothing new in this suggestion. It has been done before, in America no less, only a few generations ago in the golden time of Camelot, and the results were spectacular.

Cost evaluation: basically free whether examined from a macroscocial or subcultural perspective. You could argue that there’s an opportunity cost involved in taking school time away from the classroom, but I think we can find that time quite easily if we just stop teaching kids to hate themselves.

7. Plastics

There’s no way around this: getting rid of plastics, or at any rate dramatically reducing their use, will cost a fair bit. The alternatives – glass, metal, wood, paper – are generally more expensive, less convenient, or both. But we might not have a choice about that.

Our environment is already suffused with microplastics, as are our bodies. There doesn’t appear to be any way of detoxing from them, at least insofar as we know. They don’t biodegrade easily, so what’s already there will be there for some time. Meanwhile, there’s very good reason to believe that the drop in sperm count is at least partly due to the endocrine-disrupting functions of plastics.

At the very least, certain particularly toxic formulations, such as bisphenonal A, should be banned entirely. New plastics should be tested extensively for endocrine disrupting effects, and that goes for the biodegradable alternatives such as mycoplastics, too – since they can be broken down biologically by design, they can probably enter the body much more easily. Plastics in general should be presumed guilty until proven innocent.

Contact with food and drink should absolutely be minimized, if not eliminated entirely. Plastic packaging, plastic water bottles, and so on, should simply be banned, and replaced entirely with what we used previously: glass bottles and jars, aluminum cans, cardboard boxes, paper bags, and so on. This will somewhat reduce the ability to store food over long time-frames, but we shouldn’t be doing that anyhow.

Cost evaluation: at a macrosocial level this intervention is pretty expensive, although deposit systems for glass bottles and jars will help to keep costs down. At a subcultural or individual level, limiting exposure to plastics is somewhat doable, but ultimately futile given that in the cases of many common items there are no available alternatives.

8. Contraception

No discussion of the means of raising fertility is complete without an examination of the means of reducing it.

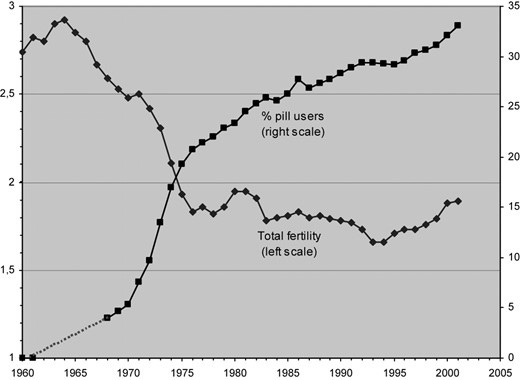

The birth control pill hit the total fertility rate like a bomb. In numerous Western countries, fertility plummeted following the introduction of hormonal birth control, with the drop in fertility mirroring usage of the pill almost perfectly. The example of France, above, is more or less typical of other Western countries, as can be seen in the following plots.

These graphs were obtained from what looks like a fairly detailed study of the fertility impact of hormonal birth control: Demographic effects of the introduction of steroid contraception in developed countries. After comparing fertility rates and birth control usage, the author concludes that while there is certainly a substantial reduction in fertility following the introduction of the pill in numerous countries, that pattern doesn’t follow universally. An obvious example is Japan, which is the final country in the above plot. Hormonal birth control was only legalized in Japan in 1999, and women there remain suspicious of it to this day. Nevertheless, Japanese fertility is infamously low, and in fact has been lower than most other developed countries essentially all throughout the decades following the introduction of birth control.

The author of the study speculates that the main effect of hormonal birth control has been to reduce the number of unwanted pregnancies, but that in the absence of this technology people will find other means of avoiding babies if they are so motivated – for instance, abstinence, the rhythm method, condoms, pulling out, and so on. Conversely, if they want babies, the availability of the pill won’t stop them: all they have to do is not take it.

I suspect the study’s author to have been strongly motivated by social acceptability when writing up his conclusions. There’s no question that cultural factors, such as the desirability of children or the ideal number of children, will have a considerable impact on family formation and size. He uses the example of the abrupt drop in Japanese fertility in 1966 to illustrate the powerful impact culture can have: according to Japanese astrological beliefs, the year of the Fire Dragon was a bad year for girls to be born, as they would have a difficult time getting married, and a large number of Japanese parents simply chose to forgo having children at all that year.

Nevertheless, humans are not wholly rational animals, and by and large we do not have an instinct to make babies so much as we have an instinct to have sex. Before 1960, a great many of us owed our origin more to the passions of our parents than to their premeditation. By rendering sex optionally sterile and therefore largely eliminating ‘unwanted’ births, the total number of children is reduced. While there are certainly other factors that can impact fertility, it seems specious to attempt to argue that widespread usage of contraception hasn’t done so.

There are other, second-order effects of widespread hormonal birth control usage on fertility. It is associated with obesity, thus rendering women less attractive, as well as with mood disorders, which also renders them less attractive. In some cases it can result in permanent sterility. It can also affect a woman’s pheremonal responses, causing her to be attracted to an unsuitable mate: how many relationships drag on for years, after which the happy couple finally decide to have kids, the woman goes off birth control, discovers she is no longer attracted to her man, and the newly unhappy couple splits up?

Exactly what should be done about this is another question. The most obvious answer would be to simply ban it outright, treating it the same way that e.g. anabolic steroids are treated. Whether this would have much of an impact is debatable. Men who want to use gear usually have no trouble obtaining it, and I suspect the same would be true of women who wanted to ensure access to their Sex In The City pills.

Anathemetizing it via propaganda is probably a more effective response in the long run. Once a drug has been synthesized, eliminating it entirely is effectively impossible, and attempts to do so using the criminal justice systems generally result only in rich criminals so long as demand remains high. If, instead, the demand for the drug is reduced by stigmatizing it – for instance, by associating its usage with trashy skanks – its usage can be more effectively reduced in the long run. Again, Japan is a salutary example here: even twenty years after it was legalized, only about 1% of Japanese women are on the Pill, largely because they don’t trust something designed to mess with their body’s natural hormonal balance. Propagating a similar attitude within our own culture is likely to be a more successful means of reducing its prevalence than banning it, and indeed I’ve heard at least anecdotally that young women are already starting to refuse it due to its various side effects.

I considered writing a separate section for abortion, which technically isn’t the same thing as contraception. Preventing pregnancy and terminating pregnancy are distinct activities, morally as well as physically, but both come down to interrupting the natural connection between sex and babies. The main difference is that legally restricting abortion is more likely to be successful in reducing its use.

Cost Evaluation: Since the birth control pill costs money, not using birth control costs nothing. Reducing supply via law enforcement would likely be quite expensive; reducing demand via propaganda is probably relatively cheap. As for abortion, banning or at least heavily restricting it certainly doesn’t cost much.

9. Village Life

For whatever reason, urban centres shred fertility like nothing else, while small town and rural living seem to do the opposite. As discussed in Part 1, there are likely several reasons for this, not the least of which being that when you feel that there’s plenty of space around, it’s easier to think that there’s room for kids. In any case, the prescription is the same: encourage as many people as possible to leave the cities, and move to villages.

The question is how to do that. Currently small towns divide into two broad categories. There are the rural wastelands, with no jobs, elderly populations, rampant drug addiction, and so on; and there are the boutique tourist towns. No one wants to move to the former, and the few young people born there tend to leave as soon as they can. The latter are expensive, and insofar as they attract younger people, it tends to be professionals in the thirties who already have their 1.5 children. In both cases there’s a demographic gap, between about twenty and thirty: if you’re young and single, villages are the absolute last place you want to move to, because there’s no one to date.

Some countries, such as Italy, Spain, or Japan, have tried attracting young people to their dying villages by offering abandoned properties for a song or even literally paying them to move there. So far this hasn’t had much success. Cheap houses or a small stipend aren’t worth being isolated in the middle of nowhere, with no schools, stores, nightlife, or what have you.

These kinds of programs might be more successful if they adopted a tribal settler mindset: rather than trying to draw in individual people or families on a catch-as-catch-can basis, they should aim to attract entire groups, with the goal of settling abandoned areas with Dunbar-number sized concentrations of twenty-somethings, who would then be able to provide one another with the necessary human interaction and economic services. As an example, a given location could have a recruitment website, with an honour-system agreement such that once a threshold number of settlers has been reached, the settlers will relocate. Such projects could be organized spontaneously as well, as for example with the New Hampshire Free State Project.

There’s a similarity here with intentional communities, which also involve small groups of people deliberately working together to settle remote areas. However, intentional communities are primarily ideological, and tend to attract the sorts of eccentric weirdos who are strongly motivated by political or religious ideologies, which in turn tends to repel most other people even when they are broadly sympathetic to the ideology in question. The idea here would not be explicitly ideological at all: the basic concept is just getting young people to move to rural areas where they can have lots of kids.

Bringing back the factory town may be another useful tactic to revive small-town life. Corporations could be provided with tax incentives to locate research campuses, production facilities, and so on in small towns, bringing their workforces along with them. This wouldn’t have the aim of providing jobs to those already living there, as by and large such places don’t have much in the way of a workforce: instead, the idea would be to draw young workers to small communities, with the goal of starting up families in an environment as friendly as possible to large numbers of free-range children. The danger here is that globomegacorp might just uproot the facility the moment the tax break is gone, making such communities inherently precarious. This could be discouraged by means of punitive financial penalties for relocation, calibrated so as to make such behaviour fiscally irresponsible.

Cost evaluation: This is hard to say, as it depends on just how attractive the inducements to relocate to small towns would have to be in order to attract settlers and institutional employers, and how long they would have to be maintained before the settlements become self-sustaining.

10. Housing

Young families need to be able to afford homes large enough to raise children in, so expensive housing has an obvious depressive effect on fertility. This has become a pressing issue throughout much of the first world. Canada is the most extreme example: the media house price in Toronto, for example, is about $1.1 million, and overall Canada has the highest ratio of real estate price to income on the planet. For most young Canadians home ownership is an impossible dream, and since few are willing to raise children in a cramped rental apartment, family formation goes with it.

One possible answer is simply to lower expectations. Our peasant ancestors didn’t own their small plots of land or the hovels they built on them, and they were perfectly willing to raise their ten children in a one-room hut. The idea that every child in the family needs their own capacious bedchamber, with dedicated rooms in the house for cooking, eating, watching TV, playing video games, and so on, is a very recent thing. In principle, one can raise kids in a two bedroom apartment, with one room for the parents and bunkbeds installed in the other room for the kids. I have friends who do just this.

But this is far from ideal. A better answer by far is to reduce the cost of housing. The main factors pushing real estate out of reach are high rates of immigration, overly burdensome building codes and other forms of regulatory overreach that make construction unnecessarily expensive and time-consuming, the high and growing cost of skilled labour, and inflationary monetary policies that incentivize investors to park their wealth in hard assets that can’t be devalued when the central bank debases the money supply again.

The housing problem is probably one that will ultimately fix itself one way or another. The work-from-home shift is already leading to a crisis in commercial real estate. As the boomers start dying off, it’s likely that the same thing will happen in residential suburbs. There simply won’t be enough demand for the subdivisions full of McMansions. We’ll likely see a blight of decay belts inhabited only by coyotes, rats, and junkies surrounding cities all across the Western world. In such an environment it is very difficult to see how residential real estate remains expensive.

The proviso is of course that if our governments keep importing new populations from the third world faster than the suburbs can be abandoned, this scenario can be avoided for quite some time, and the price of residential real estate can be kept high. In Canada the government has been doing precisely this for decades, with the population increasing by about 1% per year until 2021, when it increased by an incredible 3.5%, entirely through immigration. Without immigration, Canada’s population would be about 23% smaller. It is almost certain that Canadian real estate would be dramatically less expensive had the government not adopted a replacement immigration strategy.

However, as noted in Part 1, birth rates have fallen below replacement in essentially every country outside of Sub-Saharan Africa, and immigration can therefore only make up for the missing babies for so long before the well runs dry. One way or another, immigration rates will have to fall.

Most of the answers to making housing affordable for young families are, in my opinion, libertarian in nature, involving deregulation and a ‘build, baby, build’ approach. Which is not to say that there isn’t a role for the state. As part of his 2024 platform Trump suggested that federal land could be set aside for the creation of a large number of new ‘freedom cities’, which in a failed attempt to make the idea sound anything other than compelling one left-wing outlet described as being “Powered By Sex and Flying Cars”. The US federal government lays claim to 28% of America’s landmass, about 2.6 million square km. For comparison, about 3% of US land or around 100,000 square km is urban, so available urban land area could be doubled while reducing Federal land holdings (and therefore wilderness reserves and so forth) by only a few percentage points.

The situation in Canada is even more stark: 89% of the country’s land mass is owned by the Crown, the vast majority of which is undeveloped wilderness. To be fair, much of this is barren tundra and frigid boreal forest that no sane person wants to inhabit, but the fact is that Canada has an enormous amount of land that is just sitting there doing nothing, at least some of which could almost certainly be developed with newly incorporated villages, towns, and cities.

Repairing the shattered housing market would require dramatic economic and political changes. Immigration would need to become much more restrictive, in order to reduce the growth in demand. At the same time, the regulatory burden would need to become much less restrictive, in order to free developers to build more rapidly and cheaply. Eliminating real estate speculation, which is ultimately driven by an inflationary money policy, would require a complete overhaul of the monetary system i.e. getting rid of the central banks and the debt-based currency, and returning to something like the gold standard. Needless to say, none of these are reforms that the present ruling class is at all interested in pursing, so in order to change any of them we’ll need a new ruling class. But then again, that’s true for most of the other reforms in this essay.

In the meantime, we might just have to get used to the idea of bunk-beds.

Cost evaluation: This is a hard one. On the one hand, building housing costs money. On the other hand, it also makes money. Reducing regulatory burden would almost certainly save society a considerable amount on balance.

11. Elder-care & Child-care

The top-heavy population pyramid caused by several decades of low fertility is one of the factors threatening to cause the Earth’s population to tip over. Caring for the old is a resource-intensive enterprise, and with too many old people society’s resources are diverted away from caring for children. With less time and energy available to raise the young, fewer young are born, and the inverted population pyramid maintains its top heavy distribution even as the population crashes – in essence, society is crushed under the weight of the old.

But perhaps we’re thinking of the elderly in the wrong way – as a cost, and not as a resource.

Humans are the only species with a post-reproductive life span comparable in length to the reproductive lifespan. Chimpanzee females hit menopause at about the same age as human females, but die almost immediately after, a pattern which is replicated throughout the animal kingdom: the moment the ovaries dry out, Darwin is done with you. Human children, however, are uniquely resource intensive, being almost entirely helpless when born and taking an absurd amount of time to reach sexual maturity. Our long post-reproductive life expectancy is almost certainly an adaptation to this: humans live long enough to assist their children, and occasionally even their grandchildren, in raising their own young.

In almost every human culture, the elderly are cared for by their own children, and in exchange they help to care for their grandchildren. Even in the last years of life, when their bodies become too feeble to do much, they serve as repositories of wisdom and help in the education of the young. Our cultural practices sever this bond, assuming that the elderly will enjoy themselves in their retirement, living on permanent vacation far from their offsprings’ offspring, with the last years of their lives spent being expensively cared for by strangers in nursing homes. It is as a direct result of this that our elders are a net cost, and it is within this framework that this cost threatens to flatten the economy in the coming decades.

An obvious solution is for society to simply return to using the old the way nature intended: as aids to child-rearing.

The work-from-home shift may assist in this. One reason that the elderly don’t tend to spend much time caring for the young is that their children have moved a considerable distance from home, as a result of which they only see their grandchildren on holiday visits. With more people working from home, there is less need to move away to find work. Multigenerational neighbourhoods and households can start to form again more easily when more people are working from home.

However, a lot of old people don’t have children. The large population of aging DINKs and SINKs have no grandkids to help care for, and no kids to help take care of them in their old age. This is precisely the state of affairs that makes the old so expensive to care for in the first place. One solution here would be to combine nursing homes with day cares, and even schools. There are already pilot projects exploring this possibility, which is apparently quite popular with the participating elderly who, rather than sitting around feeling useless, feel like they are contributing to society.

So far most of these programs seem to be more focused upon the emotional benefits for old people, with the advantages for toddlers being mainly conceived in terms of making them more comfortable around the aged. Instead, we might do better to look on the elderly as a low-cost labour force optimally suited to playing an auxiliary role in child-care. We should expect that care homes double as day cares, and that old folk are there to pull their weight by helping to raise the next generation, as a matter of course.

Cost evaluation: It seems to me that combining day cares and care homes should be a money-saver overall, since it should somewhat reduce the cost of looking after the elderly (who can be expected to be overall healthier and happier thanks to the presence of children), while dramatically reducing the expense of looking after children (since the elderly will now be providing much of this service essentially free of charge).

Concluding Thoughts

The intent of this work has been to emphasize that sub-replacement fertility, far from being an intractable disease of our civilization, is a fully solvable problem. By propagating the memes of reproduction, the social status associated with large families can be raised, and children made desirable again. By dramatically reducing our utilization of plastics, eliminating novel toxins masquerading as food from the agricultural system, and including physical training as a core element of our children’s education, the young can be made beautiful and energetic, and therefore both attractive and fertile. By introducing novel matchmaking technologies it can be made easier for the young to find potential mates, while encouraging new courtship norms can simplify and smooth the transition to marriage. Discouraging the use of contraception goes almost without saying. Remote work offers the possibility of recombining professional and family life, while remote education can liberate young women from vocational training regimens developed with the reproductive lives of young men in mind – in particular, enabling them to interweave their educational and child-rearing activities, or more easily postponing education until after they have born children. Economic incentives can be used to encourage a migration to villages and rural areas, where the additional space makes child-rearing both easier and more attractive. Finally, the elderly can be used as auxiliary child-minders and educators – a role for which nature largely intended them.

It seems unlikely to me that the states of the current world order will adopt the measures I suggest here. By and large our current governments are comprehensively antinatal, with a set of economic and social policies that, regardless of whatever family values rhetoric they may espouse, conspire together to push fertility in one direction: down. This suggests that the developed world’s collapsing fertility is not due to an accidental confluence of unrelated factors, but is the product of a deliberate policy implemented through multiple chemical, biological, sociological, and economic vectors. Whether depopulation is motivated by a Malthusian fear of an overcrowded world, by hostility towards the world’s economically dominant ethne, or by simple greed, the end result is the same, and it should not be imagined that the existing elite will change course any time soon. Adoption of the policies described here on a large scale will require a circulation of the elites, which is beyond the scope of this essay.

While it is unlikely that existing elites will allow states to adopt policies aimed at encouraging higher levels of fertility among their native populations, there are already budding subcultures that have started trying to push in the other direction. Some, such as the Amish, are religious and traditionalist in nature; others, such as the pro-natalists, are more secular and technological. While the solutions proposed here can generally be adopted by any interested group (and indeed, many of them already have been – the Amish are no strangers to household industry, for example), my hope is that some of these solutions may be of some assistance to the more technically oriented groups. A future without Amish farmers would surely be a depressing one, but so would a future without starships.

Either way, the future belongs to those who show up.

Thank you for reading! If you’ve found this interesting, you should probably

And you should definitely

so you don’t miss the next essay. While you’re waiting for that, I have a large number of essays on a wide variety of topics, some of the most popular of which are collected here: on the DIEing Academy, cognitive pain tolerance, America’s prospects in WWIII, Aztec metaphysics, Tonic Masculinity, the Great Demoralization, the WEF’s failing grip on the human imagination, the policy changes that might follow a Canadian civil war, the pernicious influence of safetyism, who are the useless eaters really, and asteroid mining. All of them are available in their entirety for free. That’s right, no paywall!

The incredible generosity of my noble patrician benefactors is to thank for this. If you’d like to join their number, it’s as easy as hitting the

button. Upon joining the elite ranks of paying supporters, you will be invited behind the scenes to join the rest of the Barsoomian buccaneers in our secret orbital base on Deimos Station, as we gather our forces for our imminent invasion liberation of Jasoom, which you primitive mudhuggers know as ‘Earth’.

In between writing on Substack you can find me on Twitter @martianwyrdlord, and I’m also pretty active at Telegrams From Barsoom.

There would be a reduction in the number of calories per acre. One acre of corn generates around 12 million calories a year; an acre of soybeans is about half that. By contrast, a dairy cow will yield about 5.4 million calories of full-fat milk per year (assuming 6.2 gallons a day and 2400 cal per gallon), whereas a cow raised for beef will yield a lower limit of about 1 million calories in meat (assuming a 1500 pound animal, of which 60 percent is edible meat, with 1134 calories per pound of beef. Note, however, that this leaves out the organ meat, which is extremely nutritious and largely neglected in the modern diet: nose-to-tail consumption of the animal would increase the number of calories somewhat).

I've been feeling a bit guilty for not doing something special for my paid subscribers, and since this post was a lot of work to put together (10,000 words, damn ... I think this is the longest thing I've written yet on Substack), I decided to put most of it behind a paywall. For now. I'll take it out from behind the paywall in a week, but paying subscribers get the first crack at reading this, and at ripping my ideas to shreds in the comments.

This is great, lots of sensible ideas. I will say that "idleness" is not generally a word that can be accurately applied to a mother looking after a nursing baby, unless she is a) neglectful or b) has an absolute potato baby, and they are rare.

Baby rearing is usually very hands-on and physical. My baby only started having reliable, >20min naps after 8 or so months, and that was my housework time. Previous, he usually only slept in the day being walked in the pram, and hated a sling. I've been able to do freelance WFH for 30-60min per day, but only since he's been about 14months old and naps better (and can mostly toddle about with me while I do housework).

My point is, there is not much WFH you can safely or reasonably do while looking after little babies/toddlers. School-age kids may be a different matter though, and even just losing the commute time is helpful for balancing child-rearing and paid employment.