I’m Already Bored With Generative AI

Seriously, what’s the point?

Over 20 years ago, I got interested for a while in transhumanism, and started reading every book on the Singularity I could find. Don’t judge me too hard, it was the 90s, the world was a brighter and more optimistic place then. The dream of merging with software and cloning my consciousness to spread out to explore the Galaxy in a thousand different immortal machine bodies was quite shiny to my teenage imagination.

Inevitably, I came across the Silicon Valley shyster Ray Kurzweil and his book The Singularity Is Near, wherein he confidently predicted that the exponential acceleration in number-crunching power embodied in Moore’s ‘Law’ would achieve escape velocity sometime around, well, now. As this happened, we’d see one field after another fall to the geometrically improving cognition of of our syntellect offspring.

For the last several months, we’ve watched as machine learning tools such as stable diffusion and large language models have seemingly proved Kurzweil correct, effortlessly producing superficially incredible artistic and linguistic confabulations that dazzle many an eye. Surely artificial general intelligence cannot be far off?

At the time I was reading Kurzweil’s sales pitch, I became aware of a program he’d written to compose poetry, which sounded intriguing enough that I acquired the free .exe from his website to play with. It was remarkably similar to the LLMs that have been impressing people so much lately. The artificial poet was essentially a random text generator that had been trained up on the oeuvres of a large selection of famous poets. You could tell it to compose a sonnet in the style of John Donne, or a limerick using the vocabularly of Shakespeare, and it would dutifully draw from the indicated lexicon to spit out some garbled nonsense in the specified metre.

Kurzweil’s mechanical poet was fun to play with for about a day or so, before it got boring and I went back to more interesting pass-times like playing Shadowrun with my stoner friends. Kurzweil suggested that the software could be used by writers to derive inspiration, which is the sort of tone-deaf bullshit that only an engineer who thinks of literature in terms of statistical word frequencies could come up with. You need some sort of lightning-like insight to compose good poetry, possession by the genius loci in the play of clouds across the mirrored surface of a skyscraper, a visit from the muse through the hot glance of a passing girl. Poetry isn’t inspired by a random word generator. If inspiration for poems is going to come from poems rather than the natural world, it needs to come from actual poems, written by actual human beings. To engage with Rilke is to commune with a mind that was groping towards a way of communicating its brush with ultimate reality through the narrow keyhole of human language. The Duino Elegies aren’t stochastic character strings linked together according to frequentist pattern matching, they’re a directly apprehended religious experience filtered through a human being’s language centre.

I. The Visual Arts

Fast-forward a couple decades, and tools like Midjourney take the Internet by storm. Like so many others, I got interested in these new tools, enough that I even threw one of the companies a few dollars for a few hundred credits with which to synthesize images. I spent a few days learning how to use it, reading up on prompt engineering, playing with the software and trying to get it to do what I wanted, and failing abysmally. Oh, I could make it create incredibly detailed, visually arresting, attention-captivating images more or less effortlessly. That was the easiest thing in the world to do.

Getting it to make the image I wanted, when that image was more complex than ‘a gnome with a red hat sitting on the top of a green hill’ was essentially impossible. And even for such simple images, half of the time the gnome would be wearing a green hat and sitting on a red hill.

This made me think about the striking generative AI imagery that’s been getting shared around so much. A lot of it looks great, sure. But how much of that is smoke and mirrors? How often are we seeing a relatively faithful translation of the vision the human user had in their minds, rendered with the skill of a mechanical Rembrandt? And how often did the user have something completely different in mind, but got something that looked cool and said, eh, this looks neat, I’ll just share this?

There’s always some tension between the human imagination and the ability of the human hand and voice to bring that vision to life on the page. The ability to do this at all well is why we have such tremendous respect for the technical skills of the arts – and every artist is quite convinced that they’re absolute crap at it, because they know how wide the gulf is between what they saw in their mind’s eye, and whatever they were able to clumsily scratch onto a page in their hamhanded attempt to communicate it.

Still, though, the experience of working with stable diffusion felt a lot less like having a silicon neocortex, and a lot more like collaborating with a digital downie who could produce perfectly amazing imagery, but had no idea how the parts fit together. And this isn’t surprising, because there’s no actual mind there. It’s nothing but a statistical inference program, a few billion software neurons trained up on a few billion images that knows that the word ‘person’ tends to correlate to images that have faces and hands, but has no idea what faces or hands are, aside from patterns of pixels in a data array. This doesn’t only result in the hideously deformed hands so commonly produced by generative AIs, but in a a lack of conceptual depth that universally afflicts the images produced by this method.

As before with Kurzweil’s mechanical poet, I played with the software for a few days, across a few different platforms, and then rapidly became bored. Sure, the images looked looked very cool, and it was diverting seeing how rapidly the machine could generate them. But they were utterly meaningless. That inevitable emotional flatness, that absence of symbolic intent, that missing fingerprint of a human mind that lurks behind every genuine work of art, led to a rapid loss of interest. At least on my part. AI generated imagery suffuses Google image search results, now. Perhaps the rest of the species simply hasn’t caught up with me.

At first my naive hope was that stable diffusion could be used to rapidly generate large libraries of apposite illustration for my writing. It became quickly apparent that getting the most out of the tool requires that the user already have some degree of deep familiarity with the arts, such that they can call to mind a wide array of artists, styles, composition techniques, and the technical terms for various kinds of perspectives and lighting. The wider and more specific one’s knowledge of such matters, the better one could use the tool, which in retrospect shouldn’t be surprising given that the linguistic component of the training data undoubtedly included the descriptive elements composed by artists themselves, art critics, and art historians. On top of this there are technical aspects unique to stable diffusion, such as quirks of phrasing1 or certain magic keywords2 that can be deployed in order to obtain the best results.

When all such factors are combined it seems to me that learning to use this tool well requires a considerable investment in time and effort. Not everyone will be interested in putting in the amount of time required to get really good at this (I certainly wasn’t), so I expect prompt engineering to become a new creative profession, just as the film camera spawned the photographer. I don’t think human creatives are in as much danger as they might fear.

From an artistic perspective, it isn’t in truth all that obvious to me that stable diffusion is really that much of a game changer. It can generate imagery suitable for commercial websites, no doubt. It can be used to touch up photos. One idea that’s occurred to me would be to feed in a stream of photographs, say a dozen or so, of your dinner party or whatever. No matter how many shots you take there’s always that one dingus making a weird face or looking away from the camera3. The AI could perhaps distill from the combined images what the perfect group picture would have looked like.

So, a glorified photoshop, ultimately, which will speed up workflow for graphic designers. Aside from flattering the vanity of Instagram influencers with digital makeup and the illusion of successful diet plans, I don’t see how this is useful.

But as a generator of art, capable of autonomously replacing the human artist? I think that’s literally impossible, except in the case that the prompt engineer has gotten so good, and invested so much time and energy, in coaxing the machine to bring forth as closely as possible the vision in his mind, that in earlier times he would have put just as much time into learning how to paint well.

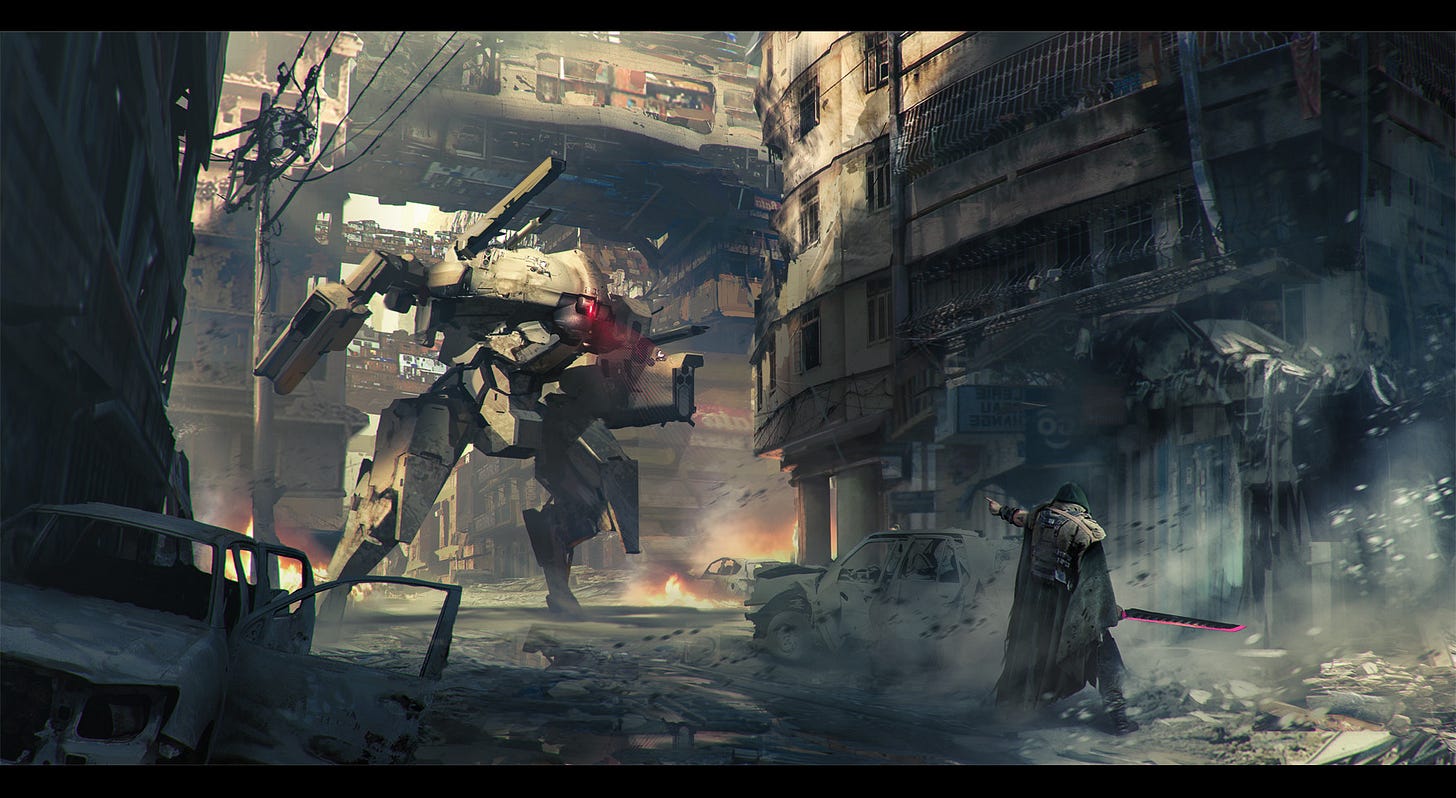

Recently I was called out in the comments for using AI imagery to illustrate my essays, a charge I was annoyed and amused by because I go out of my way to curate images from human artists, sometimes spending an hour or two a day browsing art sites. My go-to site is ArtStation, as it tends to contain a lot of the science-fiction themed imagery I prefer due to the large community of concept artists that have made it their home. My usual method is to search a keyword, any random word that occurs to me really, and then scan through the thumbnails that come up, looking for something striking or visually interesting that catches my eye. Most of it is crap, of course – 3D renders against black backgrounds, cheesy game environments, terrible paint-by-numbers fan art. But lately the site has become lousy with AI, and these are now my particular bane, because the one thing AI imagery is really good at is grabbing human attention. It’s got that combination of detail and glossiness that draws you in from your peripheral vision with a promise that there’s a lot to see here, something that will reward a closer inspection with delight and amazement. Then I look more closely and realize it’s just more generative statistical trickery, and my soul feels like a bird must after a mirror tricks it into trying to get into a fight with its own reflection.

I’ve noticed, however, that over time my eye has gotten very good at recognizing AI-generated imagery. This ability to detect the chip-print of the machine is not something I can easily express in words, it’s not like a checklist of qualia that I can rattle off. It’s much more intuitive than that. The best way I can express it is that emotional flatness I referenced earlier, that sense that the image doesn’t quite fit together, that it doesn’t entirely make sense ... and not even in the nonsensical fashion that an image made by a schizophrenic doesn’t cohere, but in the sense that it was assembled by something that doesn’t understand that there’s anything to cohere in the first place.

II. The Letters

When Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer technology came along I was, as I imagine many writers were, rather nervous. I had a nightmare vision of a future Amazon business model, in which customers could pay the behemoth CBDC$10 per month for their own personalized AI entertainment composer. This would work from a model of their personal aesthetic preferences, as inferred from social media posts, web browsing history, credit card records, Amazon purchases, and Kindle reading patterns, in order to auto-generate sumptuously illustrated, open-ended stories perfectly tailored to their individual psychological desires. The horror, for me, is on two levels here. First, that human writers would become entirely obsolete; second, that the human mind would become trapped in an endless hall of mirrors. For a particularly terrifying vision of what this could look like, see Mark Bisone’s The Games You’ll Play and The Games That Will Play You.

I’m not so worried about that anymore.

There’s a conspiracy theory that Amazon’s Rings of Power was written by an AI. From the very beginning critics were pointing out the complete incoherency of the plot. Nothing in it hangs together; things just sort of happen, according to a dreamlike illogic that only makes sense at first glance, with character arcs that lead nowhere. The dialogue is nonsensical, possessing the superficial appearance of high fantasy profundity but evaporating into word salad when one tries to parse its meaning: “Do you know why a ship floats and a stone cannot? Because the stone sees only downward. The darkness of the water is vast and irresistible.” What the hell is that supposed to mean?

Maybe the writers of the Rings of Power got in over their heads and decided to get help from friends at OpenAI without telling Bezos. By all accounts they’re talentless hacks. Or maybe Bezos wanted to see if he could ultimately replace his writing staff with generative AI, thereby massively streamlining the creative process, with an eye towards rolling out the nightmare business model I described above.

In any case, if it was written by an AI, it was an abysmal failure. Viewers universally rejected it. The only people to benefit were movie critic YouTube, for whom the project was a goldmine of tone-deaf absurdity.

I’ve found myself similarly bored by ChatGPT as I was with stable diffusion, and for similar reasons. It’s just a hypertrophied text prediction algorithm that was fed Wikipedia and Reddit, and it’s quite obvious that it doesn’t understand anything it writes because there’s nothing there to do any understanding. I’ve heard v4 is a huge improvement on v3, although I’ve not bothered playing with it yet and am a bit skeptical it will pass the Turing Test4.

In large part my boredom is because it isn’t at all obvious to me what the thing could possibly be useful for, by which I mean, useful to me.

Is it going to save me the trouble of writing essays and stories? Why on Earth would I want it to do that? I enjoy writing essays and stories. That would be like designing a machine to have sex for me.

During his cage matches with the machine

spent a fair bit of time trying to come up with at least one actually useful application of the technology, and the only thing he was able to think of was a glorified grammar checker: something that would contextually notice when you’d forgotten to include a word or used the wrong version of ‘to’. Which would surely be useful, but hardly a game-changing technology, if you’re a writer5.Friends of mine who work in web development have found that it’s quite useful for scraping content from commercial web pages and rapidly rewriting it in a somewhat different style, which I suppose makes their lives a bit easier. They’d do this kind of thing in any case, but doing it by hand takes 5 times as long. I suppose this means that lorem ipsum might be used a bit less in the future, although I’m not sure how much of the webdev time budget is taken up with composing text as supposed to writing the back-end code.

Probably the most creative application for ChatGPT has come from Aristophanes Athenaeum , who wrote up his proof of concept in Honey, I Hacked the Empathy Machine. Aristophanes’ idea, which he demonstrates via direct experimentation, is to weaponize ChatGPT in order to argue with oversocialized midwits on the Internet without having to devote any intellectual or emotional resources to the task.

If you’re a middle-management HR type, you can use ChatGPT to compose your memos for you, which gives you more time for Zoom meetings. Your bosses can use ChatGPT to summarize the reports you send them. As @Charles Eisenstein pointed out, the same dynamic applies in the educational system: teachers can have ChatGPT design their homework assignments, students can then deploy LLMs to do their homework, and the teachers can then grade the AI-generated essays using AI. Vast quantities of high-quality text can fly back and forth, with minimal if any human involvement.

We could of course extend this to the journalistic and social media sphere: have the AIs write up the news of the day, while other AIs populate the comments section and write the tweets. We can make Dead Internet real, if we want to.

There is no doubt that these things are now possible to do.

But why do them?

What is the point of having machines write text about things no human cares about, which will be read only by other machines, which are incapable of caring about anything?

Why not just ... not do those things, if we care so little about them?

What do we get out of this?

I’ve been wondering this about machine learning for some time, now.

III. The Natural Sciences

Data science has been getting very influential in the exact sciences. It’s the new buzzwordy thing, and university administrators positively dote over it due to the vast torrents of funding that sluice onto campus when it is invoked. Under the hood it’s all juiced up statistics, Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulations and multi-variable regressions and Bayseian posterior probability distributions and the like, which are tools that scientists have been using for some time, but anyhow.

Years ago I was attending a journal’s club seminar, at which a doctoral student was presenting a paper – not his own work, it was something he’d found in the literature, which is the whole point of a journal’s club – which described a machine learning project in which the data scientists had trained up their system to replicate images that were indistinguishable from those synthesized from computer simulations of a physical system. The AI wasn’t conducting original simulations. There was no actual science under the hood. It was merely creating synthetic images that so strongly resembled the visualizations derived from the original simulation that they were, to human as well as mechanical senses, indistinguishable. At the end of it we were all – at least those of us who weren’t data scientists – left scratching our heads. “But why though? What is this actually good for? What did anyone learn from this?”, was the general sentiment, to which the data scientists had no real answer.

A curious thing about data science that I’ve noticed is that few of them seem to understand what science is actually for, that being to extend human understanding. Note those last two words: ‘human’, and ‘understanding’. They are very important.

So you’ve got your learning model with its hundred billion neurons linked across multiple software layers, and you feed it endless terabytes of synthetic training data until it starts providing good results. Then you turn it loose on a novel, real dataset, and it spits a result back out at you. You ask it for an answer, and it gives you one. It might even be a good answer. It might even be the correct answer.

But what have you gotten from this?

Nothing, because you don’t understand how it got that answer. And because you don’t know how the answer was arrived at, your understanding has not increased by a single epsilon.

The machine is a black box, and because it is a black box you are not much better than a cashier with a calculator who’s never learned her times tables.

So, you’re a bit more skeptical than the cashier, of course. You fancy yourself a scientist. You don’t just trust the answer that comes from the black box, and so you take the time to check the answer, to see if it holds up, and then to try and puzzle out what it actually means. The machine can’t tell you what it means – it has no idea itself, least of all about what ‘means’ means. So you’re back to relying on the human mind to make sense of it.

Now here’s the thing. The human mind has two hemispheres. The right is specialized towards intuition, and tends to deliver instantaneous, gestalt understandings that it is quite terrible at explaining. The left hemisphere specializes in plodding, linear logic. It takes forever to get anywhere, and is quite lost on its own. In the normal way of things, the right hemisphere provides the answer, and the left hemisphere then checks that answer by working out the various relationships between its working components. We moderns have been taught to distrust our intuition, and to rely entirely on logic – we have a whole mythology built up around the scientific method and how it supposedly arrives at its conclusions via disinterested empirical hypothesis testing, which is not at all how it works in practice.

And here we are, having learned to suppress our intuition, to ignore the flashes of raw insight that come from it, because these are so difficult to parse through the suspicious language of the left hemisphere, and are after all unverifiable for others ... and we’ve ended up building vast electronic contrivances that essentially perform the same function as our right hemispheres, providing answers that it can’t explain to users who can’t understand them without putting in enourmous analytical effort.

Would it not have been easier, and more rewarding, simply to use our brains – our entire brains, and in particular the most powerful parts of our brains, which is to say the right hemisphere, whose entire purpose is to rapidly and efficiently correlate all inputs to produce an instantaneous comprehension of reality – than it was to build AIs?

If you’re already a paid supporter of Postcards From Barsoom, you have my deepest and most heartfelt gratitude. Your support makes my writing possible. If you enjoyed this essay, or you’ve enjoyed previous essays, and you have the resources to do so, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. If you take out a paid sub, you might even develop superpowers. What is certain, however, is that a paid sub gets you in to Deimos Station.

In between writing on Substack you can find me on Twitter @martianwyrdlord, and I’m also pretty active at Telegrams From Barsoom

e.g. sprinkling the same word multiple times throughout the prompt in order to emphasize its importance to the AI.

“Beautiful, striking image, trending on ArtStation, Unreal 4D render”

It’s usually me.

Although I’m quite sure that everyone who thinks it is passing is failing that test themselves.

Frankly I wouldn’t trust it to do that anyhow, in its current bowdlerized form. “I have added three missing articles, and corrected two spelling errors arising from inconsistencies between British and American English. In addition to that I have added qualifying statements to six instances of potentially harmful misinformation, and have substituted acceptable alternatives for thirty-nine instances of hate speech.”

Happy Easter, everyone! I hope you're all having a wonderful time with your families.

I guess in a culture where most mainstream "art" is stupid and shallow agitprop created by NPC mongoloids, it makes sense that corporate media factories would use a soulless and uncreative computer to replace their stable of soulless and uncreative "artists."