Poast fizeek – Plato, probably

Seven years ago, I decided to start lifting weights.

There were several factors that prodded me into this.

I’d just finished my PhD, and with one grand, multi-year project under my belt, I felt confident that I could take on another.

I’d started looking at myself, openly and honestly, in the mirror, and finally noticing the belly that now bulged below the sagging moobs that hadn’t been nearly so pendulous the last time I’d really let myself see what I’d let myself become by letting myself go. Years of being glued to my chair, staring at a screen as I lost myself in endless hours of data analysis, cutting the stress of a doctorate with Kraft Dinner, beer, binge-watching, and pot, had gradually, imperceptibly, inflated my gut even faster than my ego. Long walks, yoga, and riding my bike to and from the office had not been as sufficient as I’d imagined. Comparing the sad sack of shit I saw in the mirror to pictures from back in my early 20s was the stuff of Lovecraftian tragedy.

I’d gotten interested in right-wing cultural politics. Years of increasingly deranged cancel culture, of watching as friends that I’d thought to be intelligent, sane, balanced people on the right side of history got mind-jacked by the Skinner box and reduced little by little to little more than bugmen with little souls animated by little ideas about ‘equality’ and ‘justice’ that they wielded like daggers against everyone who looked like me ... one day, I thought to myself, these people are insane, everything they say is insane. So I started looking up those people being criticized the most viciously by the people I’d once respected. My introduction was Vox Day, who the science fiction writer Charles Stross was ripping on at the time. Vox’s blog and its comments section provided the entrance to the rabbit hole, and soon enough I’d discovered /pol/, right-wing podcasts, and all the rest. Over a period of weeks I immersed myself in the meme culture of the Alt-Right, and its savage humour ripped away my illusions and burnt away my emotional triggers with an agonizing, glorious catharsis. To enter the wilds of /pol/ in those days, even just to lurk, was akin to shamanic initiation, for it forced you to confront horrors, to face the possibility that everything you’d been taught to treat as sacred and beyond question was nothing more than a lie, that your entire worldview had been carefully constructed from raw falsehood ... and in the midst of this horror, to laugh.

Unlike the left, for whom one was beautiful at any size, for beauty is relative to the eye of beholder, and for whom even the articulation of a physical ideal was somehow vaguely fascist, the right – by which I mean not National Review conservatives, but the reactionary, traditionalist right – insists on fitness and strength. Ideals are central to the memetic architecture of right-wing thought. To be taken seriously, one must at least be moving towards those ideals, one’s vector must be one of improvement and development rather than entropic dissipation.

And so, for all these reasons, I decided to start lifting.

Before going to the gym for the first time in many, many years, I decided that I should have some baseline against which to compare myself. I didn’t know the first thing about working out, but I did know that push-ups were a thing. I couldn’t even remember that last time I’d done a push-up, but it seemed as good a measure as any, so I decided to see how many I could do.

I couldn’t even do one.

My weak, skinny arms could not even lift my distended torso a lousy single time from the floor.

I had to drop my knees to the ground, the way we’d let girls do push-ups when I was in the army.

No one was there to see this humiliation. Only I knew of it. But the shame of it was fuel.

The centrality of strength training and bodybuilding to right-wing culture is a source of perennial consternation to outsiders.

The objections of the left, motivated as they are by resentful destructiveness and a hatred of all things beautiful and strong, are of little interest to me. The left merely wishes to emasculate men, to make them soft, pliable, self-effacing, and dependent, for the left feeds on weakness and misery – the weaker and more depressed its male extensions become, the more ferociously powerful the horde. The left is like an entropic vortex. To get sucked into it is to be subjected to a constant harassment of passive-aggressive discouragements that inexorably communicate, in a million different ways, through little comments and body-language and tone of voice, that physically powerful, virile men are to be regarded with suspicion. You don’t want to be one of those people. One of those gym-bros, those frat boys, those meatheads. Everyone knows it’s more important to be intelligent than strong, and being strong means you must also be very stupid. What are you wasting time in the gym for? Here, man, I made pot brownies, let’s talk about the gender spectrum. How do you even know you’re straight, anyhow? Like have you ever even, you know, tried it?

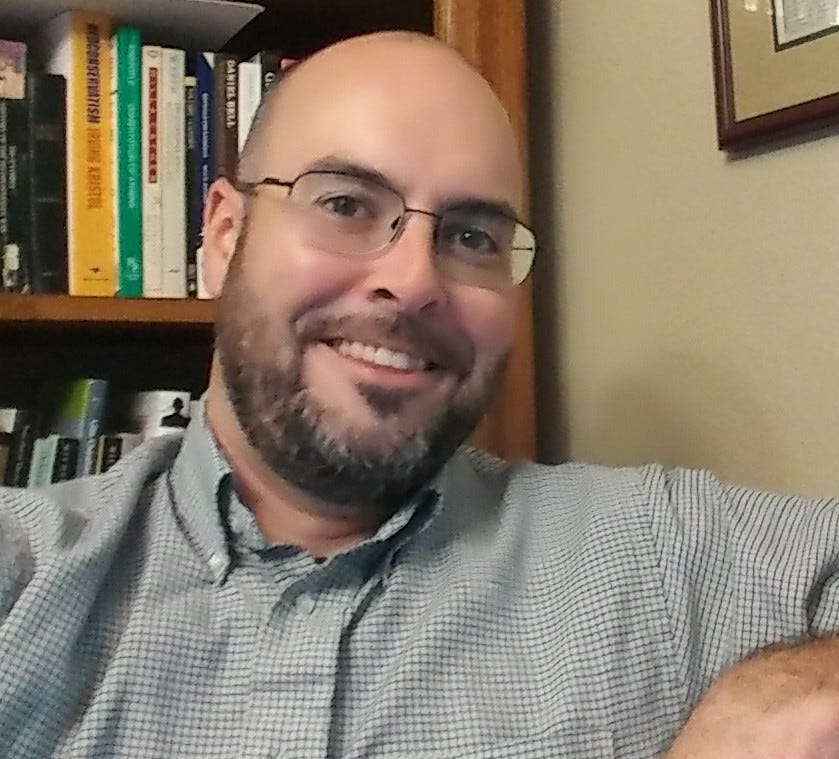

The complaints raised by conservatives, who after all are on the periphery of the right-wing core1, are more interesting. One such piece, I Don’t Even Lift, Bro, was posted a few days ago on The American Mind, a sort of hybrid conservative-right wing project affiliated with the Claremont Institute. The author, Adam Ellwanger, is an English professor who styles himself a writer of right-wing op-eds.

This is him:

I do not post his picture to be unkind. There would be a certain hypocrisy to that. I’m an anon, or at least a pseudon, and I have no intention of doxxing myself. Prof. Ellwanger had the courage to put his face out there, attaching it to the tweet thread in which he posted his American Mind essay, and to simply use it to mock him would be gauche.

However, one should keep that picture in mind while examining the three arguments Ellwanger deploys to bro-shame the right-wing bodybuilders. Consider the source. When I started to read his essay, I expected to be angry, or at least annoyed; by the end I was simply sad, as when one looks at a yipping Pomeranian and pictures the wolf growling in the shadows that was its distant ancestor. I do not want to be cruel to Ellwanger. I want to help him. My intent with this essay is not to mock, but to exhort. This is a gin and tonic, served up in the hope that the reader emerges refreshed and energized.

His arguments are essentially that:

1) muscles are mostly useless in modern society, and their cultivation is a waste of time and resources that are best deployed in more productive pursuits;

2) the obsession with physique is simply the flip-side of the total neglect of the body, and as an aesthetic the built body is both unnatural and ahistorical;

3) that this obsession with the body emerges from the same font of individualistic narcissism as the liberal cult of the consoomer self which it claims to oppose, that it is, as Ellwanger puts it, more reflection than rejection.

These saddened me, because they miss the point entirely. They are an attempt to intellectualize a culture that is, at its core, a fundamentally spiritual phenomenon. It is not abstract, but experiential, partaking more of revelation than logical deduction. It cannot be understood from the outside, absent direct experience. It cannot be effectively problematized without knowing it, and the only way to know it is in the flesh ... but once it is known in such a fashion, one will no longer even desire to problematize it.

Those who know, know.

So perhaps it is not to be wondered at that these objections crop up repeatedly. There is a certain kind of man to whom they appeal, indeed seem quite natural. I know this well, for I used to be just that sort of man. I made the same arguments, and I thought I was very funny and clever to make them. But they were just a cope. An excuse. A defence mechanism, to reassure myself that it was okay, indeed preferable, to be squishy and weak. After all, that meant I wasn’t wasting my time, I wasn’t one of those vain narcissists, I was one of the smart ones. All just cope and nonsense.

Of the three, it is most fundamentally the first – that muscles are useless in technological, post-industrial, push-button society – that is, I think, at the root of this failure to understand. The argument from aesthetics, and the argument from vanity, are ex post facto justifications.

It’s certainly true that, for members of the laptop class, a well-developed musculoskeletal system is of little practical utility. One can get by quite well with a flabby body. Taken to its extreme, there’s no real reason to even be able to move one’s own weight – we have mobility scooters, after all, and in the age of handicapable access ramps one does not even need to get off the scooter to navigate a staircase.

Homo simulacris as a disembodied brain in a jar may be Yuval Noah Harari’s erotic fantasy, but is not (yet) a description of reality. But it’s not far off from how virtual man lives. Insofar as he thinks of his body, it’s little more than eyes to stare into the black mirror, fingertips to caress it, and a second set of fingertips with which to stroke his flaccid member as the palantir feeds porn into his limbic system. I exaggerate for effect, here, but I think the Very Online will recognize themselves in this homonculus more than they might care to admit.

Of course one might object that they are not themselves mere coomers, addicted to an endless loop of sexual imagery. At least not to a degree beyond their control, haha ... haaaa. No, not you. You engage with the online world as professionals, perhaps even as Serious Intellectuals, writing Important Essays about tax policy, foreign affairs, abortion, the necessity of Catholic integralism to realize the Good, the Beautiful, and the True in the lives of men, the foundations of American Constitutional thought in classical liberalism, the finer points of the difference between equality and its mutant offspring equity, and the implications of the phrasing of the last Supreme Court decision for the next2. You are a culture warrior, with important things to do and only so much time in the day. Given all of these matters of real importance, spending hours of your life pumping iron to get perfect definition in your deltoids is a mere distraction, a form of procrastination akin to vacuuming your cat instead of writing your next very important white paper, which will after all certainly prove to be the decisive salvo that will finally break the back of the regressive left.

What you miss in all of this is that you are not a brain in a jar. You are an embodied being, and your body consists of more than just your eyeballs, your fingertips, and your dick. You do not just think with your central nervous system, but with the entirety of your body. An organism is a unified whole. Everything you do, every movement you make, every word you speak, every thought that passes through your mind’s eye, involves your entire being. When an athlete runs down the field to catch a ball, it is not just his legs and arms that move, but his mind that coordinates them, his spirit that motivates him. Why would you think it is any different with a scientist, a poet, an artist, a philosopher? Do you imagine that Tesla thought only with his brain?

Ellwanger invokes that smiling old trickster Socrates, likely thinking to score a point against Bronze Age Pervert and his army of neo-Hellenic frogs. “[T]he modern imagining of that vision is largely anachronistic: Socrates fought in the Peloponnesian War, and no historical accounts suggest that his build was especially muscular.” Leaving aside that this statement already notes that Socrates fought in a war, and was in fact renowned for his fierce temperament in battle (having saved his pupil Alcibiades by charging into line of enemies) and for his endurance (going barefoot in winter, simply to show that he despised comfort), perhaps there is no such record of his physique specifically. I’m not a classicist, I don’t know. If so, it may simply be because, for the Greeks, it was such a basic assumption that a man who had neglected his body was not worth listening to, that Plato did not feel the need to specifically mention Socrates’ perfectly defined pectorals. It is notable that Socrates himself said,

It is a shame for a man to grow old without seeing the beauty and strength of which his body is capable.

Hardly the sentiment of an idle fatbody. It’s worth noting that Plato’s name (actually his nickname; his given name was Aristocles) meant ‘broad-shouldered’, and he was known as a champion wrestler. There is a story that he would sometimes settle debates by standing up and flexing. I have no idea if this is true or a fabrication of shitposting anons. However, I can believe this. Just look at Chris Langan.

The historian Thucydides, from whom we learned essentially everything we know about the Peloponnesian War, who was himself a general as well as a scholar, and who arguably practically invented historiography, had this to say:

The Nation that makes a great distinction between its scholars and its warriors will have its thinking done by cowards and its fighting done by fools.

The keyboard cavalry of the culture war fight with words, ideas, and memes, yes – not with their fists. It is a grave error to infer from this that you can be an obese neckbeard and still be effective in this struggle. A flabby body will produce flabby thought; weak arms will produce weak rhetoric. This is not mere analogy, it is biology. The entire tenor of your thinking is a complex product of hormonal cascades. Adipose tissue is estrogenic, it makes you think like a eunuch. Testosterone insufficiency will inflect your manner of thought, the topics you direct your attention to, the way you approach them, the conclusions you draw. You think that you are thinking with your brain, but in truth you are thinking with your belly-rolls; your brain is merely there to rationalize what your abdominal padding has already decided upon.

The great danger of our time is that we are given every encouragement to softness. Like Xerxes in the historically inaccurate but highly glorious 300, modernity requires only that we kneel.

Fine, you might say – exercise is good, mens sana in corpore sano and all, but why lift weights? Why not just go for a run? And in truth, running is not the worst thing. Some time ago

published what I thought was a criminally underappreciated essay, Office Slob to Thureophoros: A Guide to Running, that made the case for developing one’s ability to run far and fast as a means of hardening the body and tempering the soul. If this is your path, run it. There is no question that it will inure you to pain, which is very important.I can speak only to what has worked for me, and for a great many others. Personally, I abhor running – as a heavy-set endomorph, I’m just not built for it. But there are also biological reasons for why, in the current historical age in which male bodies are assaulted from every direction by endocrine disruptors, I do not think running is the answer. Endurance cardio produces cortisol, which inhibits testosterone. Perhaps this is why marathon-running middle managers are such soft-spoken fags.

Heavy weight-lifting, by contrast – and by this I mean compound lifts with free weights, not jerking a nautilus machine back and forth like a factory worker – are highly testosterogenic. This is especially true for barbell squats and deadlifts. This alone helps to counteract the effects of microplastics, water supply birth control pill runoff, relentless female nagging in the digital longhouse, and all the rest of the influences that have depressed the serum testosterone of the average zoomer down to what would have been normal for a sexagenarian a generation ago.

As a practical matter, there is the afterburn effect. Lifting weights damages your muscle tissue, and the body must expend energy to rebuild it after. This results in an elevated metabolic rate, meaning you burn calories that much faster in the aftermath. By contrast, cardio will generally burn calories only when you’re moving.

These are merely biological advantages.

Weight-lifting is also dangerous. It is very easy to hurt yourself with free weights. A barbell dropped on your face during a heavy bench press can kill you. I used to occasionally pass out for a split second at the top of a heavy overhead press, the blackness receding with the bar back in the rack position in front of my chest – an indication of a weak cardiovascular system, which thankfully ceased to be a problem over the months as I started to get in shape. This was always terrifying. What if I lost control, and the bar came crashing down on my head?

But I continued.

On one occasion, I threw out my back with a sloppy deadlift. The resulting sciatica was the most painful thing I have ever experienced. I was essentially immobilized for a week, and it took a month and a half of physiotherapy before I regained full function in my leg.

But I was back in the gym a week later, rehabbing myself with rack pulls3.

I do not emphasize physical risk only to warn. Danger is very nearly the point. Life has become entirely too safe, we are trapped in an eternal nursery that has become a prison, and it is corroding our very souls. Our lives in this luxuriously padded jail are largely denuded of physical peril, meaning we have few opportunities to develop physical courage.

Lifting weights changes this. Every time you get under the barbell to set up a squat, you wonder – will I throw out my back? Every time you lie down on the bench, you think – will I drop this thing on my face? Every time you bend over to grip the bar for a deadlift, you fret – will I snap my spine?

But you do it anyhow.

If you don’t, if you let the fear win, and stop, you’ll simply become weak and soft again. It will all have been for nothing. Mastering this fear of injury is mandatory. As you master it, you master fear itself. My readers often comment that they find my writing surprisingly optimistic, despite my often dark subject matter. This is no accident, but I was not always this way. By temperament I am something of a pessimist, inclined to neurosis and paranoia, morbidly sensitive to the darkness of the world. The devotions of the iron temple taught me to master fear ... not in some abstract, intellectual sense, but viscerally, at a carnal level. You don’t really know anything if you don’t know it in your blood, bone, and flesh. Everything else is mere theory.

It is not only fear that is to be mastered. It is also pain.

Lifting weights hurts. There is the spectacular agony that can result from severe injuries, which almost every weightlifter is likely to experience at some point in their journey. But there is also the regular, daily pain of DOMS, the delayed onset muscle soreness that is every bodybuilder’s constant companion. To a degree this can be ameliorated with proper nutrition4, and some make regular use of ibuprofen, but if you’re working out regularly your muscles will be sore, and triply so when you hit a muscle group that hasn’t been worked for a while. After my first day in the gym several years ago, I was almost paralyzed for a couple of days. The muscle pain was so intense I could barely sleep. If circumstances keep me out of the gym for a few weeks or more, this returns with a vengeance, and while not nearly so bad as that first time, but even without the detraining that comes with a fortnight’s idelness it’s almost always there. You simply learn to love this constant background of pain – the sensation of weakness leaving the body.

Over time one’s general tolerance to pain improves. Small hurts are less troublesome when you have experienced great agonies. This has an effect on one’s ability to confront cognitive as well as physical pain. The brain interprets dis-confirming information as physical injury, which is why the truth hurts. The low pain tolerance that results from a life of too much comfort produces minds that too easily shy away from unpleasant realities, and too readily take shelter in the comforting falsehoods demanded for social acceptance of we involuntary subjects of the Empire of Lies.

We do not lift merely to make ourselves physically strong, although it is self-evidently better to be strong than to be weak, just as it is better to be smart rather than stupid or beautiful rather than ugly. Nor is it merely vanity, for all that there is a narcissistic thrill to looking at one’s unclad body in the mirror and not only liking but glorying in what you see, to say nothing of the ego boost one gains from those little nods of recognition one begins to trade with the silent brotherhood of gym bros when you pass in the street. Nor is it just about mogging the fats with your mere presence, although this is always fun.

A well-developed musculature and a low body-fat percentage are not simply aesthetic, they are a highly visible symbol of status that mere money cannot buy, for they show that the spirit that suffuses that body, that built that body over the course of many years of hard grinding, is itself strong, and patient. One might peevishly argue that a doctorate in the hard sciences communicates similar virtues, for it also requires patient effort, and while I like to think there is some truth to this (although much less than there should be, given the degraded state of the credential mills), this is something you have to tell people about in person, which is too much like bragging. The body is visible to all, and it displays the architecture of one’s spirit in a fashion that is impossible to counterfeit. The spirit of a bodybuilder is a spirit that was willing to push steadily ahead through years of incremental gains, invisible from day to day, enduring pain and risking horrible injury, in order to achieve its goals. In a world of instant gratification, of impulse buys driven by algorithmically hacked dopamine circuits, of attention spans cycling down to Planck timescales in which self-awareness itself fuzzes into the chaotic nothing of the quantum foam, such patience is a fearful thing. We are willing to grind away at the culture war for years. For centuries, if need be. Are you?

And you wonder why the right-wing bodybuilders are feared, while you are ignored. It is simple enough: your yapping is not a threat to the powerful, while our very existence is an implicit refutation of everything the left lies about.

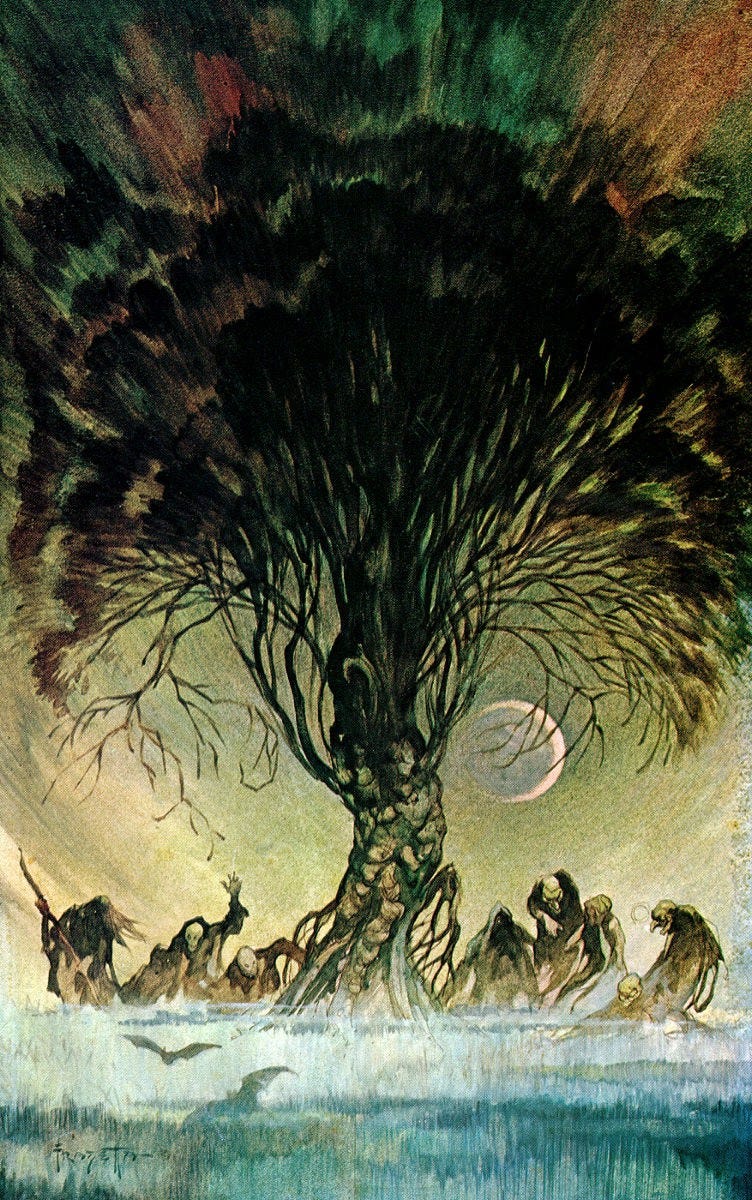

We lift to make our spirits strong, because a strong spirit cannot reside in weak and neglected flesh. Lifting is an integral element in the process of spiritual transformation that is the deepest meaning of the dissident right, which is not really about mere ideology, but is rather the liberation of buried blood memories from the barrows of forgotten warlords, the awakening of the ferocious, prowling pack-hunting apex predator within. Every time the barbell clangs down on the floor at the conclusion of a set of heavy deadlifts, that paleolithic beast growls a bit more loudly in your blood, and you carry a bit more of its soul out of the gym with you in every day.

The barbell inures us to pain and accustoms us to fear. Therefore we care less about countering the poisonous norms of the social engineers. The attempts of the trannissaries to hall monitor our thoughts by threatening ostracism for honest speech cease to be frightening, and become merely funny. Go ahead, tattle on us to teacher – we’ll laugh at him, too. Over time, our thoughts are directed less to merely complaining about the cultists of Slaanesh and the demon-princes of Tzeentch who rule over them. They become merely obstacles to be cleared, of no more importance than tree-stumps in a field. Our hands may be occupied with the hard labour of tearing their dead roots from the earth, but it is our vision of what we shall plant and build in its place that animates us.

I will leave this essay the way it began, with an anecdote.

When the lockdowns began, I had already resolved to go on a savage cut. I’d spent enough time bulking. It was time to get lean.

Then, just as I was embarking on this latest project, the gyms closed.

I showed up at my campus gym early in the morning, as was my daily habit, only to be turned away. So I immediately tried a private gym closer to home; they were open, but expected they might be closed within days, and advised me that opening a membership might not be the best idea. Cursing my luck, I then returned to my apartment complex, thinking to use the crappy workout room there, which at least had some dumbbells, only to be greeted with a sign that had gone up only minutes before, “Out of an abundance of caution....” Realizing this nonsense may well continue for longer than the promised two weeks, I went on Amazon and immediately purchased a set of selectable dumbbells, these being all I really had room for.

Over the next year5 I gradually converted my tiny bachelor apartment into a home gym, working out daily with dumbbells, resistance bands, a pullup rack, going for long walks in the morning heat, hiking in the state park on the weekends, all the while strictly limiting my caloric intake with intermittent fasting.

At the end of this period I had dropped fifty pounds, and could do fifty pushups with ease.

Whereas the median millennial, withdrawn and depressed in their jammies, got fifty pounds fatter bingeing on Ben and Jerries and Netflix.

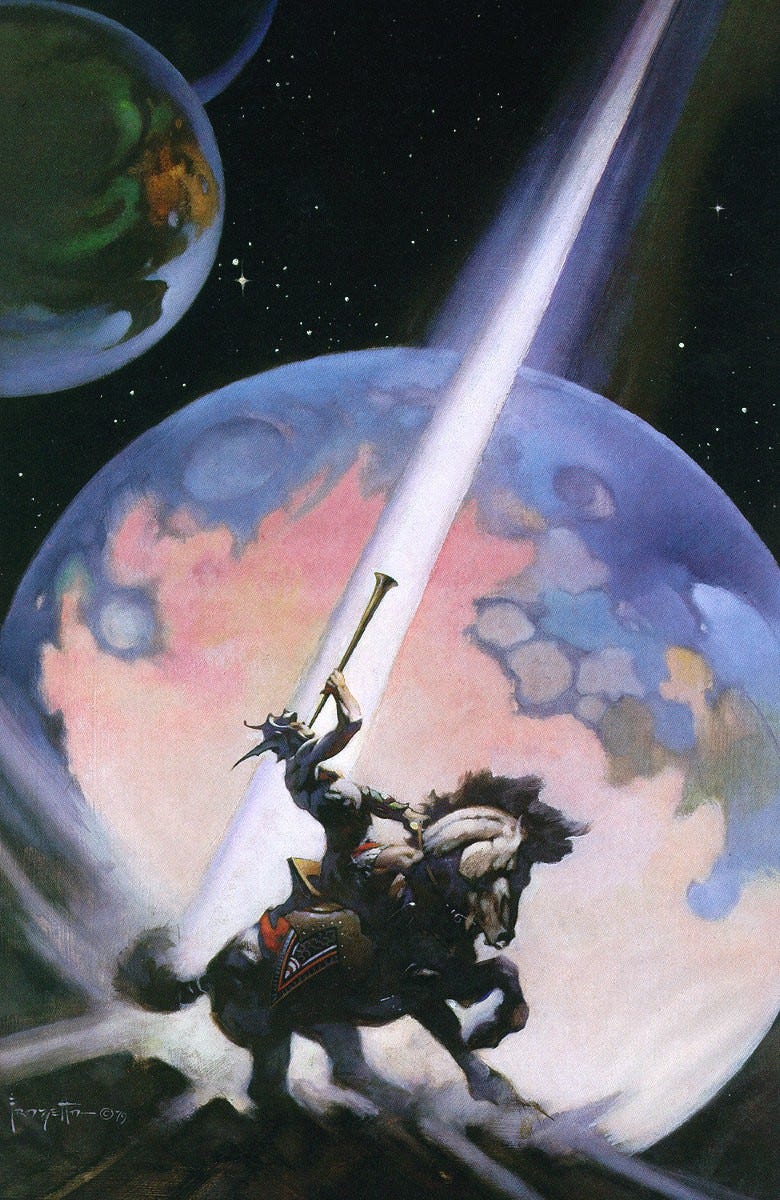

The dark lords of the World Economic Forum sought to trap us indoors, weakening our spirits as they paralyzed our bodies with the seductions of electronic comforts. The weak of body are weak in spirit, and easily ruled. I responded to this challenge with an inner howl whose intensity only grew over time. You would make me weak? I will become the opposite.

And I did.

This is not to brag, but to demonstrate. Had my soul not been conditioned by years of initiation in the mysteries of the iron temple, had it not been tempered by pain and effort, trained in patience, accustomed to swimming against the current of its own lazy desire to conserve energy, and inured to the riptides of the death cult’s devolutionary whirlpool, it would have crumbled like soggy kleenex, as so many others did, and settled back into passivity like a corpse being swallowed into the sweet stink of a swamp.

It was only when I had proven to myself that I could do these things, that I could accomplish this very basic and very simple goal, that could stop thinking with belly-fat and start thinking with blood, that I began to write.

The orthopraxy of political weight-lifting is just one of the things we talk about at Deimos Station. Rumours have been circulating, whispers from the dark corners of the Internet, that a paid subscription to Postcards From Barsoom is all it takes to join the hidden order of Deimos. Those who join, it is said, begin to change, they mutate into fearsome things filled with savage joy and midnight eros.

Much as they imagine themselves to be on the inside looking out, this is no longer the case, for they no longer instruct; the flow of ideas now goes from us, to them. And has for some years now. We are the ones making the culture. They merely adopt it.

And if you think it is the subject matter I mock, you continue to miss the point.

I’ve become very cautious about deadlifts since then, recording every set and reviewing it immediately after to check my form.

I have been finding that slonking several raw eggs a day does wonders. By popularizing the gospel of Vince Gironda, Raw Egg Nationalist is doing God’s work.

The gyms opened more quickly than that. Fuck your masks.

Great advice! Whatever the regime insists you do, doing the opposite should be your default. They want you weak? Make yourself strong. I'm doing a little but need to do much more, much more consistently! Thanks for the motivation!

I started weightlifting just before the New Year. We've got a home gym in the basement and I've spent most of our time living at this location feeling like a piece of shit for *not* using it--"Look at it, you fat asshole. It's just sitting there, promising to make you better, and every single day you make the decision to decline that offer. Stupid idiot."

I don't know what exactly finally changed and helped me move past the point of being afraid of the work, afraid of the commitment--something along the lines of a dawning comprehension that I'm not a kid anymore, that I'm about to enter one of the last decades of life where you can really meaningfully change the *kind* of person you are. So what do I want to be? A soft whinging ball of dough in a state of constant disappointment with herself? Or someone who says, "I want to do it--therefore it's going to be done" ?

Up front, I'm sure I'll never be truly cut. My very endocrine system might not allow for it, even if I didn't have about seven other ongoing projects that prevent lifting from being my highest-priority pastime. My workouts are also short and relatively easy--my priority, here at the beginning, is to build the habit of working out at all, and that's a lot easier with a 10-minute commitment instead of a 40-minute one. But every day that I go downstairs to do my girly horizontal bench press and rowers, I remember that I'm already pulling more than twice the reps I could manage in late December. When I feel the burn the morning after squats, I comprehend that the discomfort makes me strut. Shit, I feel good--I'm just proud of myself. It's healthy, it's natural, to gain fulfillment from overcoming a physical obstacle.

When the day comes, I might not be able to wrestle a stag into submission on a hunt; but I hope to be in good enough shape to help get it back to the village after.