Quick, name the the seven deadly sins.

Maybe you can’t get all of them, but I’m betting most of you can name most of them without much trouble. You’ve probably even got a favourite sin, which is half a joke, half an excuse for poor behaviour. Mine is sloth1.

Now name the seven heavenly virtues.

I’ll wait.

If you’re like most people, you’re drawing a complete blank. There’s a good chance that you didn’t even know that there were seven heavenly virtues. I’ve posed this question many times over the last year or so, both in personal conversation and on a couple of podcast appearances, such as my interview on

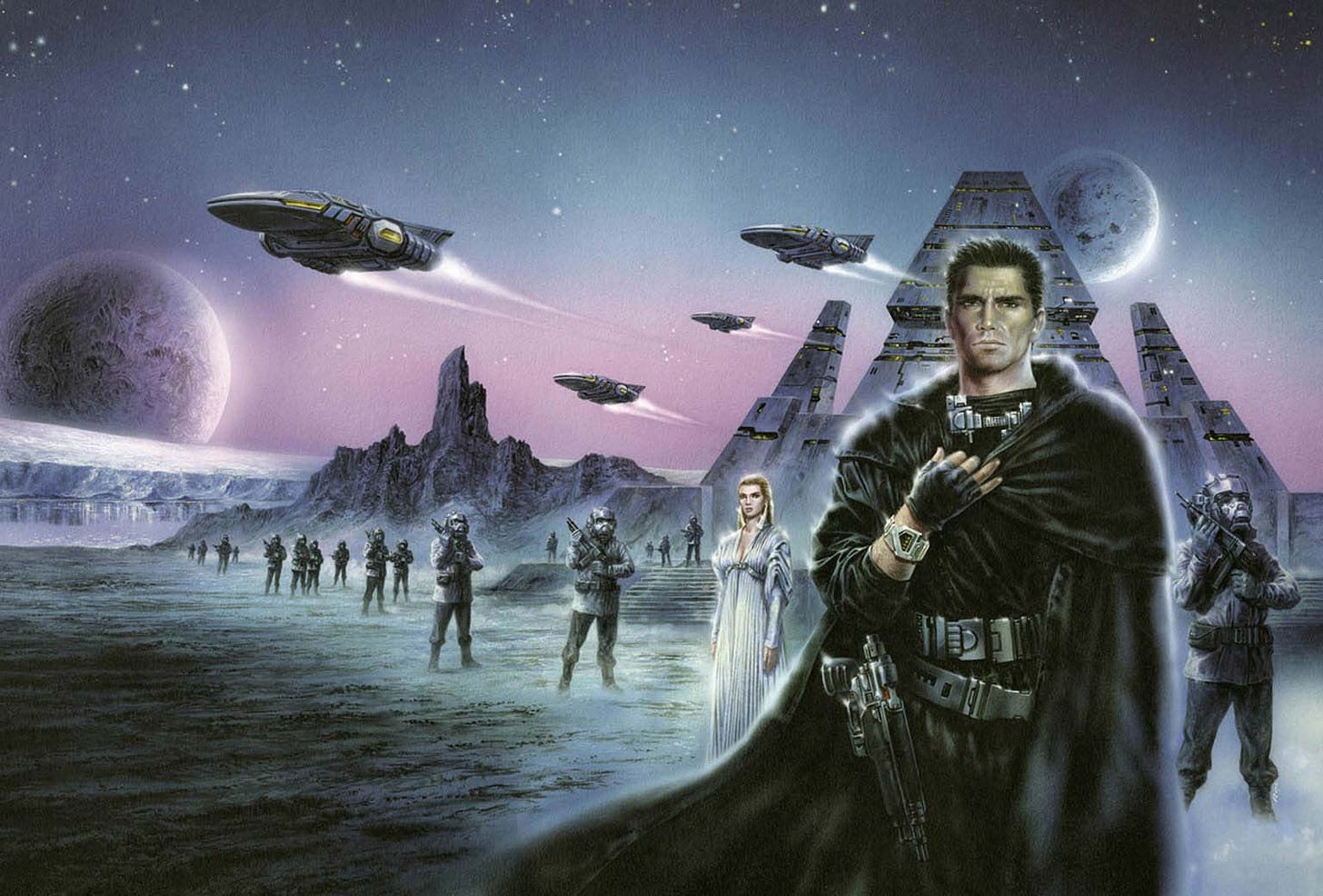

and ‘s excellent MindMatters several months ago, and during a panel discussion a few days back with the rest of the Deimos Station crew on the RealFemSapiens podcast, which you can see here if you’re so inclined:Not once has anyone ever answered that question by naming the virtues.

Virtue is not something that we often hear about.

We hear about ‘values’ all the time. In particular, the nebulous Our Values that our self-appointed betters in the incompetocracy are always invoking whenever it’s time to justify some fresh outrage against the human soul. Exactly what Our Values of Human Rights Democracy in the Rules-Based Order are supposed to be is never really stated explicitly, although it’s probably safe to say it’s some combination of intolerance, equality equity, “inclusion”, antiracism, “democracy” of course, feminism, pride, sustainability, and believing, trusting, and following The Science. Conservatives aren’t much better: their discourse tends to revolve around “family values”, as well as values like freedom, independence, individuality, the Constitution, truth, and so on.

Everywhere you turn, you hear all about values, but never about virtue. Except in the context of ‘virtue signalling’, which everyone understands refers only to the false virtue of communicating that one subscribes to the correct set of In This House We Believe dogmas. Which of course, is really value signalling.

I don’t think this is accidental, nor do I think this is a matter of no consequence. Virtue and value are not synonymous concepts.

The etymology of the two words is revealing.

Tracing the noun ‘value’ back we come to an Old French meaning the worth or price of something, with additional connotations connecting this to the concept of moral worth. This in turn emerges from the Latin valere, meaning to be strong or well, or again to be worth, which itself came from the Proto-Indo-European root *wal-, ‘to be strong’.

Virtue has an entirely different origin. The Old French vertu meant force, strength, vigour, qualities, abilities. This came from the Latin virtutem, meaning moral strength, character, goodness, manliness, courage in war, bravery, valour, and excellence, with its root in the Latin vir2 for ‘man’, preserving the same meaning from the original PIE root *wi-ro-.

What jumps out is that value has for a long time had marketplace connotations. This sense is preserved to this day in phrases such as ‘the values we hold dear’. A value is something you have, something you grasp, something that you think is important ... valuable. When we talk about our valuables, we mean exclusively our expensive material goods, jewellery and the like.

By contrast, virtue is something intrinsic to one’s character, and quite specifically something associated with well-developed masculine characteristics as revealed under the ultimate test – performance on the battlefield. You could quibble that the PIE root just means ‘man’, not explicitly ‘warrior’, but the Indo-Europeans were warlike patriarchs, so I think it is very likely that their conception of what made a good man was intimately tied up with being a good warrior.

A man has values, but he is virtuous. Virtues are not possessions, to be picked up and set aside. One must embody them. Virtue means nothing if it does not inform one’s actions.

Value is intrinsically democratic. Anyone can hold a value. All you really need to do is believe something. In fact you don’t even need to really believe it, for most purposes it suffices to merely claim to believe something, to state with words that you ‘hold a value’. One must beware the hawker in the bazaar, loudly shouting the many wonderful qualities of his incomparable goods. Merchants are known to exaggerate.

Virtue is intrinsically aristocratic. Merely saying that you’re virtuous does nothing to demonstrate that you really are, and in fact tends to indicate the opposite. Virtue is something that must be demonstrated through action in the world. It means nothing if someone says ‘I’m brave!’, what counts is whether they stand and face the enemy, or advance to the rear as fast as their legs can carry them. Developing virtue is hard, demanding work. While anyone can grow in virtue, it will always be the case that some are clearly more virtuous than others. Hierarchy emerges directly from implication: to be more virtuous than others is to be a better man than they are, which necessarily requires those others are worse men. This is no mere hierarchy of material wealth, credentials, or socioeconomic status, but a hierarchy of the soul. It has nothing at all to do with anything exterior, whether possessions or titles, and everything to do with what one is on the inside.

To value virtue above all else is to believe that what matters most is what is on the inside; and that, furthermore, this is not something which is easily changed. Making a worthless man an exemplar of virtue takes vast effort, which no one can undertake but him. It is comparatively trivial to make a poor man wealthy: merely give him money.

The egalitarian impulses that came to dominate the Western mind as the age of the mass man dawned over the last two centuries could not but be uncomfortable with a concept that, by its very nature, rejects egalitarianism. If we are all to be equal, then it cannot be the case that some are better than others, intrinsically superior in their very being. It doesn’t matter if this inequality is a result of birth and blood, or of education and experience: either way, to emphasize virtue is to draw attention to that stark spiritual fact of inequality, refuting the democratic levelling impulse with its mere acknowledgement.

It’s probably no accident that discussion of the nature of virtue and the most efficacious means of cultivating it in the hearts of the youth, which was a major preoccupation of philosophers going back for centuries, ceased almost entirely over such a short period of time3 ... to be replaced by endless prattling about Our Values, which are open to anyone who merely recites the correct shahada.

In the process, virtue has disappeared almost entirely from public life, and has been replaced with Our Values. We pretend that mere belief trumps performance, and our public discourse has become dominated by awkward euphemisms that enable us to dance around the truth, and outright fabrications that violate it utterly – it is more important to hold the right values than it is to actually be right, indeed holding the right values has become for many synonymous with being ‘good’. It doesn’t matter if you treat other people horribly, if you’re lazy, self-destructive, deceptive, cruel, selfish, manipulative, incompetent ... all flaws of character fade into invisible irrelevance under the blinding irradiance of believing the right things. Or at least saying that you believe the right things, which is even easier.

We insist that all are the same, when they are clearly not, and the very worst of us ascend like scum to the top of the cesspool. Deprecation of virtue, which must be painstakingly cultivated and regularly demonstrated, in favour of values, which anyone can claim to hold, seems to me to be a wonderful enabling factor for ponerogenesis. Psychopaths are entirely willing to say whatever they need to say in order to look good for the woke Twitter mob. Especially when you factor in the possibility of hidden double meanings. What do they really mean when they say they value ‘inclusion’? Or ‘tolerance’? Or ‘freedom’? Or ‘democracy’? Are you sure they mean the same thing it says in the dictionary?

I think we all know the answer to those questions.

I do not mean to devalue value – there’s no point in my doing that, because that’s already happened. Values have become a debased currency in the marketplace of ideas. That isn’t to say that values don’t have their uses, they obviously do.

4 provides a good description of their utility for coordinating behaviour across large groups within which, due to sheer scale, relying on detailed information as to the character of the vast majority of the other participants is impractical. However, as he points out with his concept of ‘hyper-norms’, when values become untethered from reality – as has very obviously happened for our elites, insulated as they are from the consequences of their actions – perverse disasters result:As the old meme has it, weak men make hard times, and hard times make strong men. We’re in the first part of that cycle now, you may have noticed. It is time for us, for at least some of us, to become hard men – more precisely, to become virtuous men. If we are to have a circulation of elites, as we must have, this is absolutely essential. I do not mean by this that it would be better if the next elites are virtuous; I mean that the strength that will enable them to become the next elites is synonymous with virtue.

Virtue is starting to become more of a topic of conversation, which is a good thing, but the concept is usually left every bit as nebulous as the values I’ve been ripping on. The heavenly virtues might not be a completely comprehensive map of virtue, but they’re a useful starting point, so long as one remembers that the map is not the territory. Understand that what follows is but my own hamfisted attempt at a summary of a topic on which extensive volumes have been written. I make no claim to have a deep understanding of them, or even to be particularly virtuous myself.

The first four are the cardinal virtues, recognized by the pagan philosophers as the foundation of virtue. They are:

Fortitude: strength, endurance, resilience, perseverance, courage, bravery, valour. The ability to do hard things, withstand difficult trials, press on against resistance both inner and outer. Toughness, in other words. Fortitude is notably discouraged by concepts like ‘safe spaces’; to the contrary, modern education incentivizes emotional fragility.

Justice: giving what is proper to whom it is owed, both in terms of reward and punishment, acclaim and condemnation. Social justice is, as the prefix ‘social’ implies, injustice in every way: it demands that meritorious individuals be passed over for jobs, promotions, and positions in schools in favour of those less deserving; insists that whole peoples be deprived of their ancestral inheritances of territory and culture; and gives over our cities to violent criminals and drug addicts, even as the law-abiding are viciously punished for the most minor infractions.

Prudence: this is essentially making wise decisions, doing what is appropriate in a given situation by taking into account the full context of that situation. Importantly, it isn’t just intelligence or knowledge; as present social conditions demonstrate on a daily basis, and most especially over the last few years, merely smart or educated people can be very imprudent, e.g. believing known liars on such subjects as pandemics, vaccines, Ukraine, or carbon dioxide.

Temperance: When this word is used people tend to think of the hysterical church ladies that got alcohol banned, but temperance doesn’t just mean knowing when to say no to that next drink, although that is an example. Temperance is essentially achieving the correct balance. Our society, which oscillates between a level of prudishness that would have appalled the Victorians and a licentiousness that would have made Caligula blush without even noticing the obvious contradiction, is notably lacking in temperance of any sort.

Fortitude is necessary to act in the world; justice is required for right action; prudence, to act at the right time and in the right way; and temperance, to do things in the right amount.

Temperance is often considered the chief virtue: too much or too little of any given virtue can easily become a vice. For example, being too just may make one rigid; being too prudent may become indecisive timidity; an excess of fortitude might cause one to endure too long, and to no profit, that which should not endured. Even temperance, taken too far, can become a problem: there are times when it is prudent or just to be a bit intemperate. While one should in general not overeat, on the occasion of a Christmas feast gluttony is almost mandatory. All things in moderation, even, and maybe especially, moderation.

To the four cardinal virtues, the Church added the Christian, theological, or supernatural virtues, which can be accessed only via a relationship with God. Whether you consider these to be as essential as the cardinal virtues is an interesting question; personally, I tend to think the cardinal virtues are primary, and that you can get quite some distance without the theological virtues. Nevertheless, these are times of not merely cultural conflict but spiritual warfare, so divine assistance isn’t nothing.

The Christian virtues are:

Faith: this is usually understood (and often explained by the Church) to mean something like ‘believe what the Bible says because the Bible says it’, but I don’t think ‘just trust me, bro’ is even close to how faith should be interpreted. I tend to think of it more as really believing what you believe – having the courage of your convictions, from which flows the will to act upon them.

Hope: the Church ties this to expectation of everlasting life, the eternal reward in Heaven that comes from salvation. I think of it as simply maintaining a certain degree of optimism, that as dire as things may seem in the present there is always the possibility that things will work out in the end ... and that even if they don’t seem to work out, that this too is for the greater good in the long run ... even if that ‘long run’ is long after your own death.

had an excellent take on hope not too long ago, which you should read:And finally, that which is considered in the Christian tradition to be the chief virtue:

Love: by this the theologians mean agape, the divine love of God for man and vice versa, which is often translated as charity. The other forms of love, such as eros and philia, are emanations of agape. To have love is to say yes to existence, to serve that which is higher than yourself.

The cardinal virtues are qualities of character, which can be developed and strengthened through practice and experience, but they are ultimately in a sense amoral: one can be strong, wise, or moderate, while also applying these virtues to antisocial ends. The supernatural virtues, on the other hand, seem to me to be more of a certain stance towards life, an orientation of the soul.

Merely reading a list of the virtues and their descriptions only gets you so far. Just as virtue is something that must be practised and demonstrated through action in order to grow, the best way to learn about virtue is really by example: by studying the lives of virtuous men. You could do much worse than picking up a copy of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives of the Greeks and Romans, and making a study of his biographies. This is no small undertaking: Plutarch is not written in the sound bite Tweet prose we degenerate moderns are accustomed to, and his writing is voluminous. It took me months to get through. However, his tales of adventure, struggle, triumph, and disaster make for far more entertaining reading than a dry academic monograph on the subject of virtue. Along the way you will acquire a good education in the history of the peoples from whom you came, you will at least partially reclaim some of the cultural patrimony that was denied you when the classics were removed from the curriculum to make room for social studies, but Plutarch’s purpose was not to write a careful and accurate history. Rather it was to use the lives of the notable Greeks and Romans as illustrations, in order to inspire the young to grow in virtue. Plutarch’s narratives present virtue as it really is, an indefinable elan vital that includes but is not really reducible to the list of properties given above. Any such reduction will inevitably leave something essential out of the mix. Only in the lived examples of flesh and blood, of real action in the world, can virtue really be understood at the most fundamental level.

And then, of course, reading about virtue is not at all sufficient.

Virtue is not mere words.

You must also practice it.

If you’re already a paid supporter of Postcards From Barsoom, you have my deepest and most heartfelt gratitude. If you enjoyed this essay, or you’ve enjoyed previous essays, and you have the resources to do so, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Rumour has it that paid subscribers develop superpowers. What isn’t a rumour, however, is that a paid sub is also a ticket to Deimos Station.

In between writing on Substack you can find me on Twitter @martianwyrdlord, and I’m also pretty active at Telegrams From Barsoom

At least pretend to be surprised.

Harrison, who enjoys etymology even more than I do, pointed out this origin during the discussion of virtue on the RealFemSapien podcast.

I think it was Luc Koch who first alerted me to this observation, by way of the nearly forgotten but in his time extremely influential British philosopher R. G. Collingwood.

And why aren’t you already subscribed to him?

You raise some intriguing lines of thought about the distinctions between an ethic based on "virtues" and one based on "values." Everyone has things they value, but not everyone has (or values) virtue. Values are egalitarian, but virtues are not. For some of these folks, it really does seem that any talk of "virtue" offends them because it's a reminder of how vicious they are in comparison.

Fun fact, there originally were *eight* deadly sins.

Tristitia, or excessive sadness was formerly included.

Dante Alighieri (of Dante's Inferno) somehow managed to take it out of the list. Makes you wonder if he indulged in tristitia and wanted to excuse himself (or more charitably, he cared for someone who did so). Whatever his motive, I wonder what depression rates would be if it was still considered sinful.

I uncovered this bit of history in a podcast series a friend and I are making on solutions to problems we currently face, and the first four (five?) are going to be on virtue. I'll be dropping them soon, so maybe subscribe to my 'stack if you think that's your knack.