This is the fourth in the extended post-mortem of academia, which we’re watching DIE (that’s Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity) before our eyes. An overview of the DIEing academy is given here. In Part 2, I explained how our broken academic institutions played a key role in facilitating the ongoing nightmare of medical tyranny that has consumed our lives for the past two years. The third entry in the series explored the myriad ways in which students are failed, and actively damaged, by the failing academy. In what follows, I discuss the dysfunctional academic job market, its origins, and the role it has played in deranging the minds of academics.

Years ago, after several years of being an absolutely insufferable Facebook enjoyer, I went quiet on social media. Since then I've assiduously avoided saying anything under my own name on the Internet.

Part of the reason I went radio silent was that I was finishing my doctoral dissertation, and really needed to focus if I was going to get everything done without going too far past the deadline that had blown past months earlier.

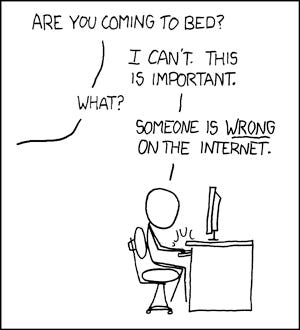

But another reason, and the reason that became the dominant reason as time went on, was that social media had simply become too dangerous for a young academic. Especially one with my personality profile: a gleeful contrarian who enjoys nothing so much as taking on the entire room in a debate, who positively glories in arguing with people who are wrong on the Internet. It was something that I couldn't help myself from doing: within minutes of checking the Facebook feed, I'd be getting into it with someone about something, and doing so in the knowledge that while there was essentially zero chance that my interlocutor would be convinced of my position (cognitive blowback being a very real thing), there is always an audience, and someone in that audience may well be won over to whatever my cause du jour happened to be if I successfully made my opponent look like an ass.

Thing was, that unseen audience was starting to change from a source of strength to a malign presence ... less amused onlookers, more disembodied eyes blinking pitilessly in the night.

As we all know, the culture started changing in the teens. The free-wheeling, robust debates of the Internet of the naughty naughties, where trolling was an art form and getting Mad On The Internet meant that you'd lost the infinite game, gave way to the censorious climate of perpetually morally outraged mobs who got their dopamine by destroying the livelihoods of those who dared disagree with whatever sacred dogma they'd thought up five minutes ago.

The moment I realized this was happening was probably the 'shirtgate' episode, in which the European Space Agency scientist Matt Taylor wore a tasteless shirt festooned with images of Barbarella to the press conference announcing the successful landing of the Rosetta space probe on the comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko. My feed erupted with outrage from fellow scientists who, of all people, should have recognized that the fact that this guy had just successfully achieved a genuine technical feat - the first landing of a space probe on a freaking comet - was perhaps of greater interest than his questionable fashion sense. Looking into it more (as one does when arguing with people who are wrong on the Internet), it turned out that the guy had worn the shirt specifically because his female artist friend had given it to him, and he wanted to do her a solid by providing her free advertising on the occasion of his greatest scientific triumph, when for a brief moment he would have the world's eye. That didn't matter to the mob: the shirt was sexist, he was a pig, and it was utterly irrelevant that it was a woman who'd given it to him and that he was trying to help that woman by wearing it.

Over the next couple of days the mob broke the guy, to the point where he recorded a blubbering apology with tears streaming down his cheeks. Well, you'll get that kind of thing with bugmen. And to be fair, we didn't know back then that there is no forgiveness: in the Church of No Salvation, sin is forever and cannot be expiated; apologies only encourage the bastards to demand more.

That lesson hit home for me. The howling mob wasn't composed of gender studies majors and professors of grievance mongering, at least not exclusively. It was the damn scientists who were his most enthusiastic persecutors. It was my friends and colleagues. If they'd destroy a guy for something so trivial, then what chance did I have - an early-career scientist without steady employment? Say the wrong thing and that would be it for my career. Whatever scientific accomplishments I'd had before would be as nothing when weighed against the terrible sin that I'd been Mean On The Internet.

All of this is a something of an extended introduction to one of nastier aspects of the contemporary academy, which is the broken job market.

You can roughly estimate the duration of a scientist's career by the dates of his first and last publications. Back in the 60s, the half-life of a scientist was around 35 years - in other words, 50% of scientists stayed in the field for 35 years. Considering that most PhDs graduate around 30 years old, that pretty much takes you to retirement.

The half-life is now 5 years. Given that most PhD students publish at least one paper before they finish their degree, and that a doctoral program is about 6 years in duration, that means that half of scientists leave the field sometime between getting their PhD and finishing their first postdoctoral position. Postdocs being generally 2 to 3 years in duration, only a quarter are left by the end of the second postdoc. It's not at all uncommon for a "young" (pushing 40 by this point) scientist to do 3 or 4 postdocs before finally landing a faculty position, by which point about 90% have left the field. That's from survey data, but anecdotally, it matches my observations quite well.

Now, let's talk about postdocs. As stated, they usually last between 2 and 3 years; some are as short as 1 year; only very rarely do they extend to 4. Finding a postdoc usually takes something like 6 months of sending out applications, during which time these applications become one's primary activity (in other words: you're not doing science while you're applying for jobs). To say nothing of the constant anxiety over what you'll do if you don't land a job, anxiety that sits on your chest like black dogs eating your soul in the small hours of the night while you're trying to sleep.

If you finally land a postdoctoral position, it will probably be on the other side of the country if not the other side of the planet. For those who want to see the world, this isn't so bad, but let me tell you: as a guy who's lived in a lot of places and rather enjoys that, pulling up whatever shallow roots you've grown, abandoning friends, and starting all over again every couple of years takes a toll. That's a lot harder for anyone who has stronger ties to a certain location, for example, because they have an especially close family or friend network. It also makes lasting romantic relationships challenging, to put it mildly. Since most academics end up dating other academics (these being the people they meet socially), this has resulted in something referred to as the 'two body problem', in which a couple's careers mean they have to live in different countries1.

Surveys of scientists who escaped from academic science almost invariably find that job insecurity and constant relocation is one of the top reasons they leave. Even if they can get another postdoctoral position, it gets to the point where it just isn't worth it to stay on the postdoc treadmill any more.

All of this raises the question of how it got this bad. What happened between the 60s, when a STEM doctorate was more or less a guarantor of life-long employment, and the 20s, when PhD holders have been reduced to a neurotic precariat?

The answer is the over-production of PhD students. See, grad students are the primary scientific work force, doing all the boring scut work of data analysis, model testing, code debugging, and the like. This is kind of insane because until they're close to finishing their doctorates most grad students have no real idea what they're doing, and through no fault of their own aren't especially productive. They're students after all; that they aren't yet trained professionals is sort of implicit in that status. As students they also spend a good deal of time taking classes. However, they're cheap - a grad student in the sciences usually gets something between $20k and $30k a year - and it's for this reason that most professors prefer to use students rather than postdocs (who are at least twice as expensive).

Why, you might ask, are the professors not doing the science? After all, if anyone knows what they're doing, it should be them, right? And you'd be correct about that. My experience is that a postdoc or a professor can accomplish in hours what might take one of their students a month to do. Only ... doing science isn't actually a professor's job.

A professor's job, as far as the university is concerned, is to bring in grant money.

See, aside from tuition, the main gravy train the universities ride are grants. Most institutions cream off 50% of the value of a grant in what they call 'overheads' - fees charged the grant-holder for the privilege of using the office printer. That's right: universities essentially charge their employees rent for the use of the facilities at their place of employment. Crazy, no? So, if you're an ambitious young professor desperate to get tenure, it's absolutely essential that you land that big grant, because otherwise the university will consider you a bad investment and drop you when your four-year trial period is up.

If scientific funding was easy to come by, that might be no big deal. Unfortunately, the success rate for most funding agencies is something like 10%. Further, in general funding agencies only take grant proposals once a year. So, if you're going to have a reasonable chance of getting a grant before facing the baleful eyes of your tenure committee, that means putting in 3 or 4 proposals every year, each of which can be something like 100 pages in length, including detailed budget breakdowns, descriptions of collaborator responsibilities, and of course a convincing scientific research plan. Each funding agency has its own particular set of requirements for submission, ranging from formatting to length to citation style, meaning that you can't just submit an identical proposal to each agency.

Assuming you do finally land that grant so that you can fund your research, congrats, you've got funding for another 3 years. Since it will take about 4 years to get another grant, now that you've gotten that grant, it's time to start writing proposals to get the next grant.

All of this means that professors don't spend their time doing science. They spend it writing grant proposals.

Of course, they're still evaluated on the basis of their scientific productivity, as determined from their presence in the peer-reviewed literature. Only, they don't really have the time to write many papers themselves. That's where students come in. If a professor can maintain a steady stable of 3 to 4 grad students at any given time, and get 2 to 3 papers out of each of them before they defend their dissertations, they can make sure they get their names on several papers every year without having to do the majority of the work themselves.

You see the problem. Universities demand funding. Funding is hard to come by. Professors need to spend most of their time acquiring funding, but professors also need to publish regularly. Grad students are the cheapest way they can turn their grants into papers, so they bring in lots of students. That results in lots of terminal degree holders flooding the market.

It's a perversion of the old medieval apprenticeship system, from which the supervisor-grad student relationship evolved. It's always been an essential part of graduate school that the student conduct their own original research. Producing a masterwork is, after all, how the apprentice becomes a master. However, one of the key unspoken understanding in an apprenticeship system is that the guild masters are regulating entry to the guild in order to maintain an equilibrium between the number of people entering it and the number leaving. The deal is supposed to be that, in exchange for years of underpaid labour, one will gain the skills necessary to enter a profession in which employment and a reasonable standard of living is guaranteed.

Apprentices are not supposed to be used as a primary source of cheap labour.

To bring this piece full circle, the overproduction of doctorate holders is almost certainly a contributing factor to the unhinged moral hysteria of wokeness.

First, the constant job anxiety experienced by academics is corrosive to the soul. It makes one desperate. For those animated by the Dark Triad personality traits, it's all to the good if some of the competition can be removed via accusations of moral crimes against [insert oppressed group here]. Bonus points if you can claim [oppressed group] status and thereby give yourself a boost in the job market. The rabid virtue signalling bloodsports of social media follow directly.

Second, for those whose souls are not cesspits of corruption and venom, the fact that even a rumour of bad thought can torpedo a career regardless of merit is enough inducement to keep one's head down, eyes averted, and mouth sealed shut. I'm ashamed to count myself among them, at least as regards social media (I've never been able to stop myself from speaking my mind in person, and for all I know, the walls having ears and all, I may well have already screwed myself).

So there you have it. If you want to understand why academia has gone insane, follow the money. The money broke the ancient contract between apprentice and master. The broken job contract broke the job market. The broken job market broke everyone's minds.

That's a physics joke, by the way. It's a reference to the three body problem in Newtonian mechanics, the canonical example being the Sun-Earth-Moon gravitational system. After centuries of trying to find an analytical solution, physicists ultimately realized that there is no solution: three body problems are inherently chaotic. Two body problems, on the other hand, have easily derived, exact solutions. At least in physics. In academia, the two body problem usually has no solution but two broken hearts. That's the joke. Funny, right?

Agree. I realize that when I was finishing my bachelor's degree, that they use students as canon fodder. I remained because I like science and couldn't picture myself working on other thing, besides I'm pretty stubborn and I still associate leaving as defeat. Now, more or less ten years later I am finishing my PhD, and still in the same conundrum, thinking what to do after that. Things have gotten worse. The corona nonsense is like the final nail in the coffin, academia is rotten.

Great breakdown informed by real life, thanks. I'm asking myself - is the academy doomed and will be replaced eventually by something else, or a variety of different approaches? My guess is yes. There are just so many problems you don't even know where to start, ranging from stiffling paradigms (left-wingism, materialism, historical and philosophical illiteracy...) to unreadable prose and authoritarian-burocratic journal policies to vast amounts of corruption and wrong incentives...