The moral evidence for sprites

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, but what counts as extraordinary?

A few years ago a girlfriend texted to ask me about something weird she’d seen. The lights had been arranged in a line, and had gone whipping across the sky. She’d never seen anything like it before. Could they have been a UFO? I asked her if maybe she’d seen a StarLink constellation, and a few minutes later she responded sheepishly that, er, yes, that was probably it.

That’s the closest I’ve ever personally come to having an eyewitness report a UFO to me. I’ve never seen a UFO myself, or anything else that might be broadly classified within the general taxonomy of a Weird Otherworldly Occurrence (WOO). The closest I’ve over come to seeing a WOO with my own eyes was many years ago. I was walking with my sister down a dirt road by a meadow near the family homestead, early on a lazy summer evening after the setting Sun had dipped behind the forest-covered granite hill overlooking the meadow, when a green fireball streaked across the sky. My sister and I gawped at one another, did you see that too?, both of us doubting our own eyes. Our mother didn’t believe us, until our father came home and reminded her of a similar event he’d seen when driving home one night.

A once in a lifetime sight, but hardly magical. Just a large meteor with a particularly high magnesium abundance. Rocks fall from the sky all the time. Counting space dust and micrometeorites, about 40,000 metric tons of material precipitates onto the Earth from space every year.

It wasn’t always the case that such a sighting could be considered mundane. The educated mind of the 18th century and before considered the notion of rocks falling from the sky to be a peasant superstition. Men of science knew that rocks fall, of course. Everything falls. But for a rock to fall from Heaven would mean that it had either been ejected from the Earth with an implausibly powerful impulse, or that it had been suspended for some extraordinary length of time in the air. But rocks don’t hang suspended in the air, and if they did then why would they fall? Therefore there was no such thing as a meteorite. QED1. It was irrelevant how many signed affidavits from eyewitnesses came in, and it was irrelevant how sober and respectable those eyewitnesses were: rocks didn’t fall from the sky, therefore if you claimed to have seen one do so you were obviously a credulous fool who had not yet been enlightened by the Age of Reason.

To its eventual credit, the scientific community revised its evaluation of the reality of meteorites when several thousand fragments rained down on the town of L’Aigle, France, in 1803. Jean-Baptiste Biot2 went to investigate, and concluded that, indeed, rocks do fall from the sky. He based this conclusion on two types of evidence, which he termed physical and moral. The physical evidence was provided by the rocks themselves. The moral evidence came from the numerous eye-witnesses who all affirmed that, yes, their fields had been subjected to an aerial bombardment.

Physical evidence is nice to have, and indeed essential for any detailed empirical study. But it isn’t always easy to come by, particularly when a given phenomenon is transient, unpredictable, impossible to replicate in a laboratory, and unlikely to leave much in the way of evidence behind. In such cases I think there’s reason to put greater weight on Biot’s moral evidence. People might be utterly mystified by what they see, they might have no explanation for it, but they’re unlikely to lie about having seen it. When large numbers of people report similar experiences, it’s silly to ignore them. Scientists, after all, are thin on the ground in comparison to the vast bulk of the population, and when you’re dealing with something that doesn’t happen often, doesn’t last long, can’t be replicated in a lab, and doesn’t leave behind any trace of having transpired, your best bet to gather information are eyewitness reports. In such a case, the human population are your sensor array.

Meteorites aren’t the only example here.

Take sprites.

Lightning in the upper atmosphere is now an accepted meteorological phenomenon, but until about 30 years ago it was considered mythical. Everyone, especially meteorologists, knew that lightning was an electrical discharge between cloud and cloud, or cloud and ground: it went sideways or down, but it certainly did not go up.

And yet pilots, who (unlike meteorologists) spend a great deal of time above the clouds, had been observing lightning discharges into the upper atmosphere since essentially the beginning of aviation. These reports were written off by the scientific community for decades, to the point that pilots stopped discussing sprites outside of the brotherhood of other pilots. It was the kind of thing you brought up around a few beers in the bar outside the airport, and didn’t mention around the uninitiated. If they claimed to have seen sprites to the wrong person, such as a meteorologist, their sanity might be called into question, which for a pilot can mean the end of their career.

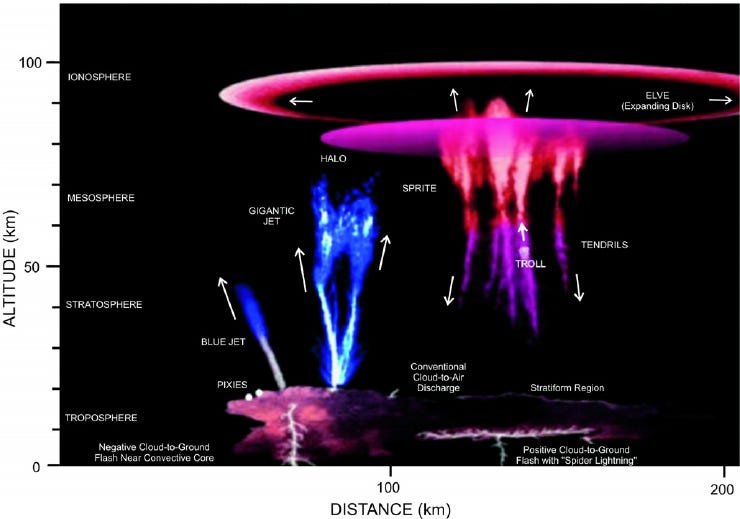

It wasn’t until 1989 that a physicist accidentally caught sprites on camera, thereby ‘discovering’ the phenomenon. Once science accepted the phenomenon was real, it could be investigated systematically. Now we know that these discharges – the taxonomy has been expanded beyond sprites, to include trolls, ghosts, pixies, and ELVES3 – go all the way up into space.

That the eye-witness reports of pilots were written off for so long is absolutely remarkable when one considers that they were provided by a group of men who: are trained to be keen and careful observers; spend considerable time in the relevant environment; are selected for a high degree of technical competence, and indeed frequently possess advanced degrees in the exact sciences themselves. If one must rely entirely on moral evidence, it’s hard to imagine a more credible group from which to receive it. Pilots are not illiterate peasants ... although, at least on the question of meteorites, those illiterate peasants were right all along, too.

If scientists had simply taken the moral evidence provided by pilots seriously, they could have started studying upper atmospheric lightning a century before they did. If they’d taken the moral evidence of peasants seriously, they could have started collecting meteorite samples several centuries earlier than they did.

You’d think that scientists – and everyone else – would learn their lesson.

It’s the same story as with sprites, really: large numbers of pilots are seeing things that they cannot explain, but because they cannot explain them (and nor can anyone else), officially, they don’t exist, and they’re crazy if they think they saw them. They’ve been having those experiences, apparently, for decades now. Not only are they seeing things, occasionally they’re coming so close that they experience near misses. Here’s an account of a large grey cube surrounded by a translucent sphere, hanging perfectly still in the air (which no aircraft we know of, whether fixed wing, rotary wing, or dirigible, can do), which two Navy fighter jets nearly collided with. It wasn’t a hologram: it had a radar signature. It wasn’t a balloon: similar objects were observed to accelerate from rest to Mach 1. So what was it? No one knows. But it freaked the pilots out sufficiently to cancel the mission.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. According to the standard set by the great astronomer and showboating popularizer Carl Sagan, “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”, a pithy rephrasing of the principle espoused by Pierre-Simon Laplace, “The weight of evidence for an extraordinary claim must be proportioned to its strangeness”. Sagan’s Standard is beloved of Reddit fedoras, who smugly pronounce it as a gotcha to write off anything outside of their worldviews.

But Sagan’s Standard rather begs the question: what counts as an ‘extraordinary claim’?

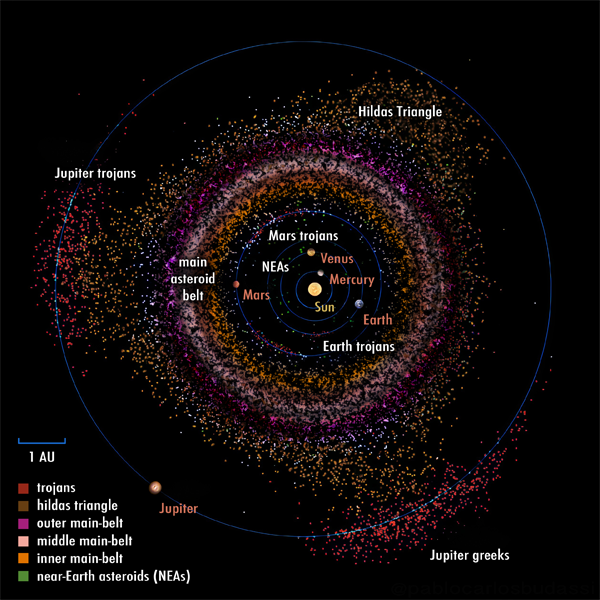

The idea that rocks can fall from the sky, with occasionally catastrophic results, doesn’t strike the modern imagination as particularly extraordinary, because we know that the solar system is swarming with something like a million known asteroids larger than 1 km in diameter, along an uncountably vast quantity of smaller objects.

Where our ancestors lived in a world of fixed stars and celestial spheres turning on eternal orbits, we inhabit an unstable gravitational pinball machine governed by deterministic chaos. We now believe that the dinosaurs were wiped out by a particularly large cosmic impact, and there is a growing consensus that human civilization was severely affected by the Younger Dryas Impacts twelve thousand years ago4.

Now, you could argue that 18th century philosophes naturels didn’t know about asteroid belt, and that therefore they were justified in considering meteorites to be extraordinary. And, it is true that the first asteroid, Ceres, was only discovered in 1801, a fact that is likely related to Jean Biot’s adventure into disreputable pseudoscience. However, comets have been known from ancient times, and Tycho Brahe – the top observational astronomer of his age, whose measurements laid the basis for Johannes Kepler’s laws of planetary motion – demonstrated all the way back in 1577 that comets were not an atmospheric phenomenon as argued by Aristotle and Galileo, but were rather located beyond the distance of the Moon. That should have ended any notions of a fixed and eternal heaven in which transient apparitions did not play a role, and opened the door directly to the possibility of comets – and other objects – falling to Earth, but strangely, it did not. Over two centuries had to elapse before the scientific community allowed itself to make the incredibly obvious connection between Brahe’s celestial observations and those of peasants. The point is, once Brahe had shown that comets were extraterrestrial bodies, the concept of meteorites should no longer have been considered at all extraordinary.

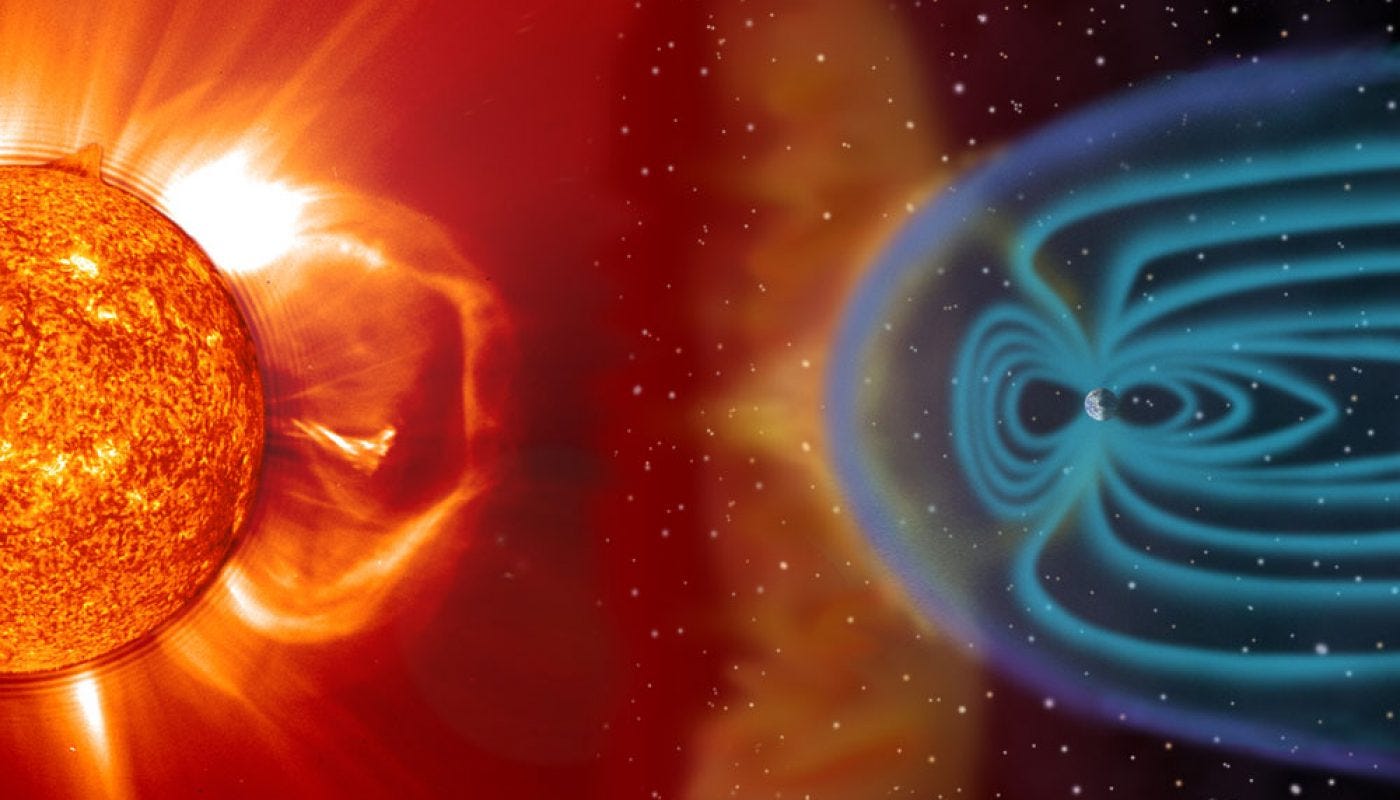

Likewise, in the case of sprites. The idea that lightning discharges can reach all the way to the edge of space doesn’t seem quite so extraordinary when one considers that the Earth is embedded in a vast magnetospheric bubble that extends out more or less to the distance of the Moon, which itself serves as the interface with a dynamic interplanetary plasma environment wracked by solar storms and cosmic rays.

The polar aurorae are a direct result of electrons raining down from the solar wind around the magnetic poles, which in extreme cases can induce telluric currents that can short out entire power grids. Given such a profound electrical connection from space to the ground, why should there not be some degree of discharge in other direction?

Now, again, you could argue that the discovery of the full extent and complexity of the terrestrial magnetosphere and the Earth-Sun magnetic connection wasn’t fully appreciated until the late 1960s, when space probes started directly measuring particle flux in the near-Earth environment, and that this was only twenty years or so before meteorologists admitted that sprites exist. However, it’s worth pointing out that the Norwegian geophysicist Kristian Birkeland was arguing that the aurorae were best explained by an interplanetary magnetic connection at the turn of the last century. He supported his contention with laboratory experiments using a terrella – a magnetized sphere embedded in a near-vacuum plasma – and field measurements of particle flux beneath auroae. None of that mattered: the British mathematical physicist Sidney Chapman ridiculed Birkeland’s ideas on the basis that you couldn’t possibly have an electrical current through a vacuum. Chapman won, and Birkeland was laughed onto the fringes of science. Decades later (after Birkeland was long dead), and space probes had vindicated Birkeland’s ideas, Chapman adopted them as his own.

Had the scientific community accepted Birkeland’s empirical evidence in favour of Chapman’s theoretical incredulity, it would have opened itself to the concept of cosmic plasmas decades earlier than it did ... and the idea that lightning can go up into space would have seemed considerably less extraordinary.

Much as those who fancy themselves hard-nosed, no-nonsense scientists and science enjoyers love to invoke Sagan’s Standard, it sometimes works against their case. For example, there are many who consider it to be quite extraordinary to claim that, for a few brief and glorious years between 1969 and 1972, men rode pillars of fire into heaven and stood on the grey, gritty regolith of the airless Moon.

Indeed, they find it to be such an extraordinary claim that, to them, it is far more likely that the only place the Apollo astronauts ever set foot was on Stanley Kubrick’s sound stage.

What’s fascinating about the Moon Landing Hoax believers is that they are utterly unconvinced by any of the extensive evidence supporting the historical veracity of the Moon landings. We’ve got samples of Moon rocks; hour after hour of video and audio; radar tracks; reflectors left behind on the lunar surface that can be pinged to this day; 3D radar mapping with modern orbiters that verify the topography in the Apollo photographs. It doesn’t matter: they know it was impossible (something something Van Allen Belts....) and find a way to explain away every piece of evidence. The claim that man walked on the Moon is, to them, so extraordinary that no evidence is or ever can be extraordinary enough to justify it.

Of course, academic scientists would never do something as silly as aggressively explain away evidence supporting a claim that they consider too extraordinary to credit. I would certainly never suggest that generations of scientists insisting that there is no reality to the UFO phenomenon are guilty of the same epistemic bad habits as Moon Landing Hoaxists.

That would be mean.

So is the claim that non-human, extraterrestrial intelligences have visited and indeed are currently present in the Earth’s vicinity, in fact, actually extraordinary?

Consider what we know.

There are something like two hundred billion stars in the Milky Way galaxy, which has itself been around for almost as long the universe itself, over 13 billion years or about 3 times the age of our own Sun. With several thousand exoplanets having been discovered over the last twenty years or so, we now know that the fraction of stars with planets is pretty close to 1, and a very large number of stars have more than 1 planet. So there are probably something like two trillion planets in the Galaxy.

Of course, we only know one planet on which organic life has definitely taken root. Considering what we know of terrestrial life in broad strokes, we see that survives in essentially every available environment, no matter how inhospitable: deserts, the Antarctic, volcanic vents, the stratosphere, cracks several kilometres down into the Earth’s crust. The range of conditions under which life thrives is very narrow, but it can cling to existence almost anywhere. Life is tenacious and adaptable.

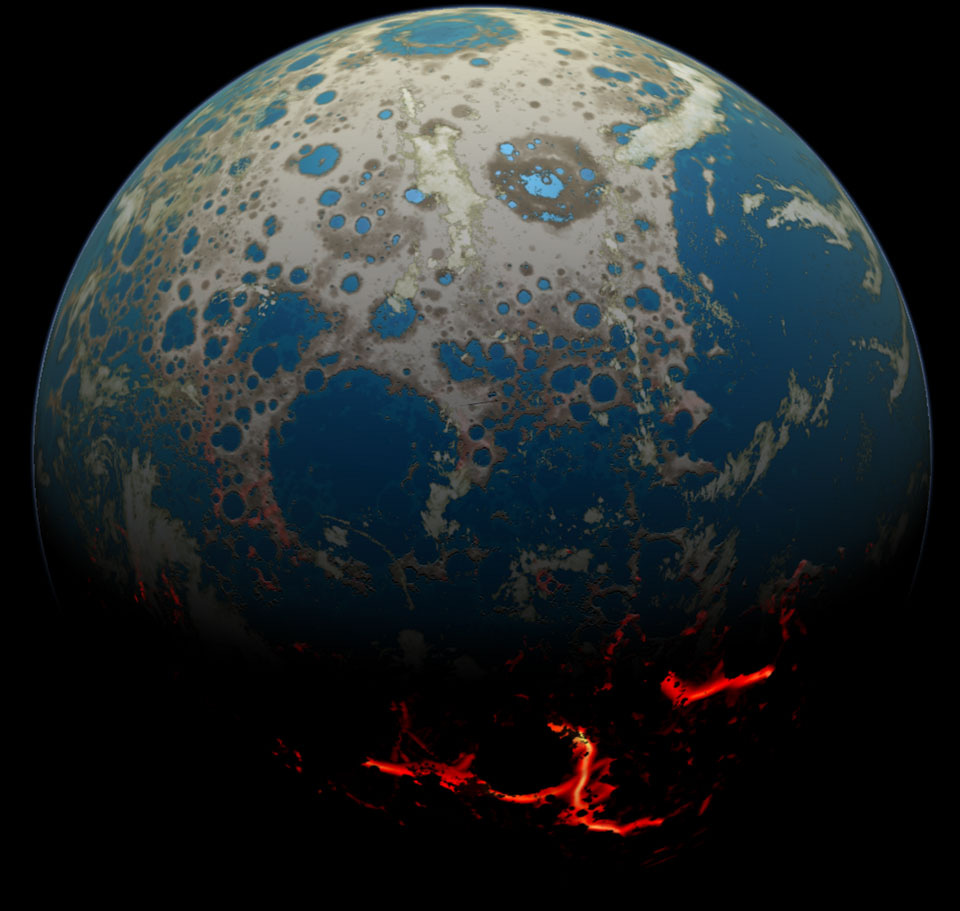

Terrestrial life is also old. Fossil evidence indicates that life started almost immediately after the Hadean epoch:

Which is to say that as soon as the Earth was no longer a hell of volcanism and endless asteroid impacts, life began.

The emergence of life more or less immediately tells us one of two things: either life was seeded on Earth from somewhere else, or physics makes the emergence of life highly probable once the conditions are right. Either way, we’d expect organic life to be found elsewhere. In fact, we’d expect it to be almost everywhere, given life’s proven ability to survive in the most punishing of circumstances.

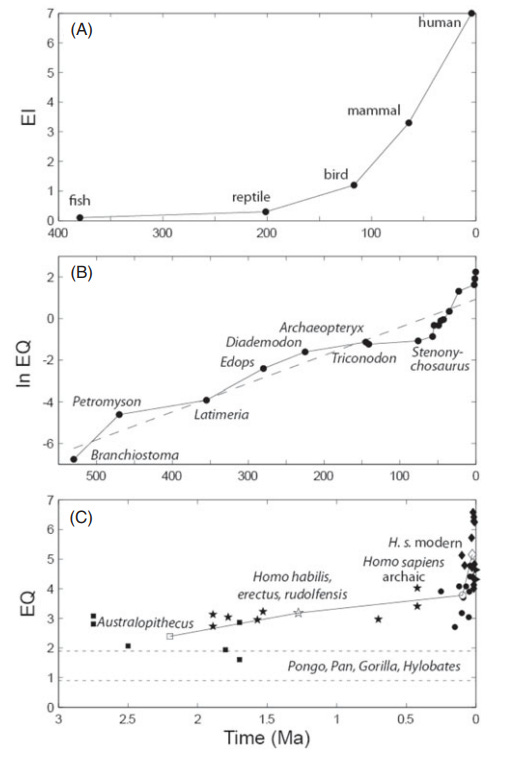

We have excellent reason to expect that life should be extremely common, but what about intelligent life? The steady increase in encephalization over evolutionary time – in other words, the tendency of brains to become larger, presumably since intelligence is almost always a competitive advantage – suggests that self-aware, tool-using intelligence should invariably develop (given time and conditions favourable to complex, multicellular life).

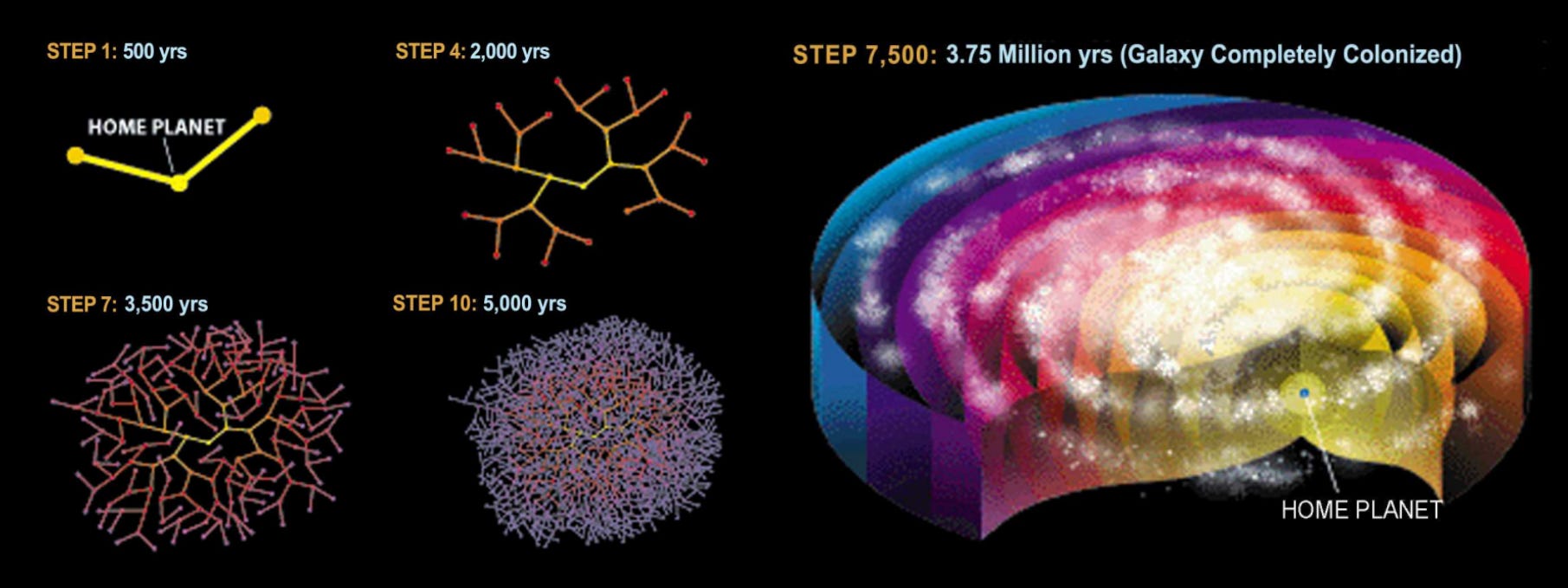

Life is invariably expansionist, and intelligent life (at least on Earth) is no exception. Once an intelligent species has developed the ability to cross interstellar distances, it will almost certainly do so. Even if their vessels are crawling at 1% of the speed of light, such that it takes centuries to cross the distance between two neighbouring stars, a colonization wave can expand across the Galaxy in less than 4 million years, or about 0.02% of the age of the Galaxy5.

Not only is there every reason to expect life, including intelligent life, to be relatively common, but there are excellent reasons to expect that technological civilization should have permeated the Galaxy long before humanity evolved. This is the source of the Fermi Paradox ... but the Fermi Paradox is predicated on rejection of every single UAP sighting in history. If even a single one of those sightings is real, there is no paradox: the aliens are here, and they’ve always been here, just as expected. They’re just not terribly interested in talking to us.

It’s just like with meteorites and sprites. Our understanding of the universe strongly predicts that we should see evidence of a certain phenomenon; we have innumerable observations consistent with that phenomenon; yet we refuse to follow the logic of our models to their obvious conclusions, instead insisting that all of the observations consistent with those conclusions are entirely the result of human error, hallucination, superstition, or malicious deception.

According to Ryan Graves, the retired Navy pilot who founded the blandly named Americans for Safe Aerospace a few years ago, and who was one of the three who testified before the House Oversight Committee at the infamous UAP hearing, his organization has received so many reports from commercial airline pilots that he estimates only about 1 in 20 sightings are reported through formal channels. Pilots generally don’t bother to make a formal report when they see something that looks like inexplicably advanced aerospace technology, for the same reason that they kept sprites to themselves: no one believes them, and their sanity and therefore fitness to fly might be called into question. It’s all downside, no upside, so they keep quiet about what they see up there.

That seems to be changing, finally. We’re now living in a world in which UAPs are a part of official reality, at least for a subset of officialdom. This doesn’t mean that UFOs are necessarily objectively real, just that they’re being treated as such by a growing number of scientists, legislators, intelligence agents, and military officers. Hearings are being held, laws passed, investigative committees formed, research projects funded.

Why it’s finally changing is an interesting question. It isn’t because there’s suddenly a preponderance of hard evidence which we were previously lacking, at least nothing that’s entered the public sphere. So far all we’ve received are a few grainy videos, which is pretty much the same quality of physical evidence supporting UFOs that’s existed since we first started discussing flying saucers back in the 40s. Nor is there suddenly a vastly larger quantity of moral evidence. If anything, eyewitness accounts of WOO are far less elaborate than they were in the heyday of rednecks getting tractor-beamed into flying saucers that were ten times larger on the inside than on the outside, having unspeakable things done to their nether regions, and being found wandering the back roads dazed and unpantsed three days later despite the whole experience having seemed to take only minutes. By contrast, dancing lights performing strange aerodynamic manoeuvres at high altitude aren’t nearly so impressive.

To be sure, many remain skeptical. And not without good reason. It isn’t like officialdom hasn’t lied to us before. They lie to our faces daily. About everything. It seems to be their main joy in life.

Broadly speaking, there are three scenarios explaining the recent flurry of government activity on the UAP subject: 1) it’s a psyop, 2) it’s a feedback loop, 3) it’s all real.

All three of them are remarkable.

1) In the case of a psyop, we’ve got a faction within the national security state whose operatives have been planting stories in the national news media at least since the New York Times Tic Tac story back in 2017. This cabal includes sitting journalists, congresspersons, intelligence operatives, and military personnel up to and including retired generals. They are going to the trouble of setting the lumbering machinery of the government in motion in order to convince at least a part of the population that UAPs are real. It’s a long con, stretching out over several years, with aims that remain utterly opaque. Gin up hysteria over an alien invasion in order to justify military spending? Introduce us to our space brothers from the Galactic Federation who will advise us to stop eating meat, fight global warming, and submit to the UN? A reader in my previous piece on this topic suggested they might simply be introducing noise into the system, the way the responses of LLMs and image generation AIs are seeded with random noise, in order to see what happens. Which is worth thinking about.

2) The feedback loop scenario is related to the psyop scenario, but pushes the psyop decades into the past. It suggests that the popular mythology of alien contact and secret government crash retrieval and reverse engineering programs has permeated the culture so deeply that it now influences people throughout the power structure who really do think it’s real. Whether it started organically, growing out of Weird Tales and Amazing Stories, or was deliberately encouraged by the Pentagon in order to provide cover for black research programs, the mythology long ago took on a life of its own. Maybe the people who know how it started are all long dead, or maybe their inheritors are in an awkward position – if they admit the whole UFO mythology started as a psyop, they’re admitting to a long-standing deception, and may risk beans being spilled on active research programs. So they don’t want to come out and admit that it was all a prank, bro, but meanwhile they’re beset with a growing posse of clowns armed with congressional powers who are demanding answers and convinced those answers exist. Awkward.

3) In the final scenario, UAPs are exactly what they look like, and the government really has been lying about their existence for generations, quite possibly while in possession of recovered non-human technology which has been farmed out to various aerospace contractors for proprietary reverse engineering, all funded by misappropriations from the defense budget by way of shameless overcharging for gold-plated toilet seats on the part of no-bid government contractors. Say, what did that missing two trillion dollars Donald Rumseld reported on 9/10 get spent on, anyhow?

All three possibilities are quite shocking. Either the government is lying outrageously now, or they’ve been lying outrageously for longer than most of us have been alive. It’s a real heads they lose/tails they lose situation. A complete epistemological shitshow, and a scandal for the ages no matter what the truth turns out to be.

The Hill seems to think that the feedback loop scenario is unlikely in light of the degree of buy-in and corroboration from highly placed officials. I’m not so sure about that, personally. I rather lean towards the explanation being some combination of all three: both/and, rather than either/or. There’s no question that the UFO mythology is fantastically influential within the collective American subconscious.

Widespread belief in UFOs has certainly percolated throughout most of society, including those elements of the state apparatus with the power to actually look into it.

But just because the phenomenon has accumulated a mythology doesn’t mean there isn’t something real at its core. The moral evidence provided by so many thousands of people witnessing inexplicable phenomena, some of them – such as fighter jet pilots – being generally considered quite credible, tends to suggest that there’s something happening that we don’t yet have a firm consensus explanation for.

And yet, personally, I don’t trust any elements in the regime. At all. Even if there’s fire where that smoke is, and I lean strongly in the direction that there is, I suspect there’s some kind of angle they’re playing. It could be a limited hangout, designed to keep the most damaging information under wraps. It could be that there’s an intent to manipulate the public by twisting the truth somehow. It could be that the timing of all of this is part of the manipulation.

Setting aside the motivations of the American state apparatus, what explains the apparent thaw in popular attitudes towards the UFO subject? Because it isn’t only the regime that’s tacitly admitting that flying saucers are real. It’s also academic scientists, such as Harvard’s Avi Loeb, who are openly discussing the subject and initiating research projects into it.

Partly, this could just be that they’ve been given emotional permission to do so: if the government is talking about it, and the media isn’t insisting it’s completely crazy, then they can investigate the matter in public without immolating their careers.

Partly, too, it could simply be that enough time has passed for the full implications of our scientific knowledge base to sink in. The tension between our understanding of the cosmos, which practically demands that there should be technologically sophisticated interstellar civilizations, and our collective refusal to connect these implications to the huge number of sightings (the National UFO Reporting Center, NUFORC, has catalogued 90,000 of them), has finally grown too great. In other words, we’ve finally started coming to terms with the sheer spatial and temporal immensity of the universe, as a result of which the hypothesis that ET exists no longer strikes people as quite so extraordinary. Now that the claim is no longer viewed as outlandishly extraordinary, people are less likely to preface their reports with “I know it sounds crazy, but....”, and we can finally start discussing the evidence – and the implications of that evidence – in the open.

Thank you for reading my meandering thoughts on this still rather fraught subject, and for your patience in waiting. It’s been a few weeks since my last update, and in my defence I have been a bit distracted with travel. I caught four flights last week, two of them to travel across North America to attend a UAP conference, and a few days later two more to come down to South America. It’s been years since I travelled, and all those flights and all that jet lag frankly hit me like a truck. Took a while to recover. That said, the UAP conference was absolutely fascinating. And yes, it is good to have finally escaped from Canada.

Anyhow, if you enjoyed my thoughts on this subject, please consider subscribing as there’s a good chance I’ll write about it again; I’ve got quite a bit more to say on it. If you didn’t enjoy this particular topic, please check out my back catalogue: everything I’ve written is in front of the paywall, and I try to cover a wide variety of subject matter to keep from boring myself, and you.

As always, in between writing on Substack you can find me on Twitter @martianwyrdlord, and I’m also pretty active at Telegrams From Barsoom.

It’s entirely possible that I’m misrepresenting the contemporary argument against the existence of meteorites. I’m not 100% sure what the conceptual grounds for doubting them were, since Newton’s Laws were certainly the accepted standard at the time and there’s nothing in Newtonian physics to rule them out.

Whom physics nerds will recognize as one of the two fathers of the Biot-Savart Law in magnetostatics, that being the relationship between the properties of an electrical current and the properties of the magnetic field it generates.

Emission of Light and Very Low Frequency perturbations due to Electromagnetic Pulse Sources.

It’s notable that the K-T extinction hypothesis was fiercely resisted right up into the 1980s, while the Younger Dryas Impact hypothesis remains bizarrely controversial to the present day. There’s something about living in a cosmic shooting gallery that seems to make comfortable older scientists deeply uneasy, a dynamic that goes all the way back to Enlightenment savants pooh-poohing eyewitness accounts of meteorites. In any case, while the historical role of cometary and asteroidal impactors remains an awkward subject in academia, the basic fact that rocks fall from space on a regular basis is not contested – it is not extraordinary.

That temporal asymmetry doesn’t change much if colonization wave moves at the much slower velocity of the Voyager spacecraft, humanity’s first and so far only interstellar probes, which are leaving the solar system at 17 km/s and could reach the nearest star, α Centauri, in about 75,000 years (if they were heading towards it, which they aren’t). A species limited to Voyager speeds would colonize the Galaxy in about 4% of the Galaxy’s age.

First, a detail not often recognized. The Fermi Paradox was first formulated by Enrico Fermi in Los Alamos at a time when national security types were worried about frequent sightings of green fireballs with odd trajectories.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Green_fireballs

The nerds in Los Alamos (Manhattan Project/cold war era Los Alamos) were split between Soviet probes and UFOs.

Second, your list of three options leaves off two or three that really should be considered.

4) unknown physical phenomena. Those cubes inside spheres are the side effect of frame dragging in a chronosynclastic infendibulum of electromagnetic time crystals. (All made up, because how should I know what undiscovered physics is going on)

5) actual woo. The UFOs are real pixies and sprites, or the astral/etheric effects of Thor throwing down with Hermes.

6) archetypes and the collective unconscious. 1,000 years ago people saw angels and demons because that is what they expected to see. These days people see UFOs (overwhelmingly in the English speaking world) because that is what they expect. Whenever some stimulus doesn't fit into available patterns it gets shunted into forms that make sense. For a fun rabbit hole, look up near death experiences by culture. (The Hindus have the best one, where they see a giant bureaucracy that sends them back due to clerical errors)

Finally, missing from the equation is the interest in space. Life might be abundant, intelligence might be an emergent property, even technological development might be common, but we might be the only species in the universe that cares about space exploration. That might even be limited just to western civilization (Faustian according to Oswald Spengler) and other human cultures lose interest after the west finishes imploding.

I'm going to be that guy who pisses in the pool it seems.

Just because something /should/ have developed due to similar circumstances sadly has no bearing on whether it exists or not. I'll use a couple of well-known conundrums:

>Why no industrial revolution during the height of Egypt, Greece or Rome? All of the requisite knowledge, materials and socio-economical base conditions were in existence. Not only didn't it happen in the Eastern Mediterranean region, it didn't happen at all anywhere until much later.

>Why didn't an ambitious empire-building colonising culture arise somewhere in Africa, rather than in Europe? The raw materials are there. No winter. Plenty of game and plenty of space for agriculture. And if we believe the "out of Africa-hypothesis", a huge advantage in time. Yet nothing like the persians, the greeks or the romans arose.

While it is both probable and plausible that there are millions of planets with life, long dead or just formed, well... compare to purposeful and conscious exploration of Earth. It didn't take off for real until quite recently, measured on our species' time of existence. Nor was it very systematically performed, initially.

And all the above things doesn't even take religion/spirituality into account, or "prime directive"-stuff. Maybe the UFOs are interstellar sociologists?

My favourite pet-hypothesis is, the dinosaurs ruled the planet for over 100 000 000 years. Obviously, they developed intelligence and sci-tech and left before the impact, throwing their ships into a slingshot orbit around some star or other, course calculated to bring them back to Earth when they could be certain conditions were approaching tolerable. A couple of decades aboard ship, tens of millions of years on the planet, thanks to relativity and time dilation due to the relative velocities.

Making the UFOs scout ships of course.

Maybe that's why Mars looks like it does? They went there because their main engines were that hypothesised kind that chain-detonates hydrogen bombs to push the ship into tens of percent of light speed?

Just spitballing. Very enjoyable read, you spoil us - also nice to see a mention of Brahe, the man with the silver nose.