The Prophet of the Twentieth Century

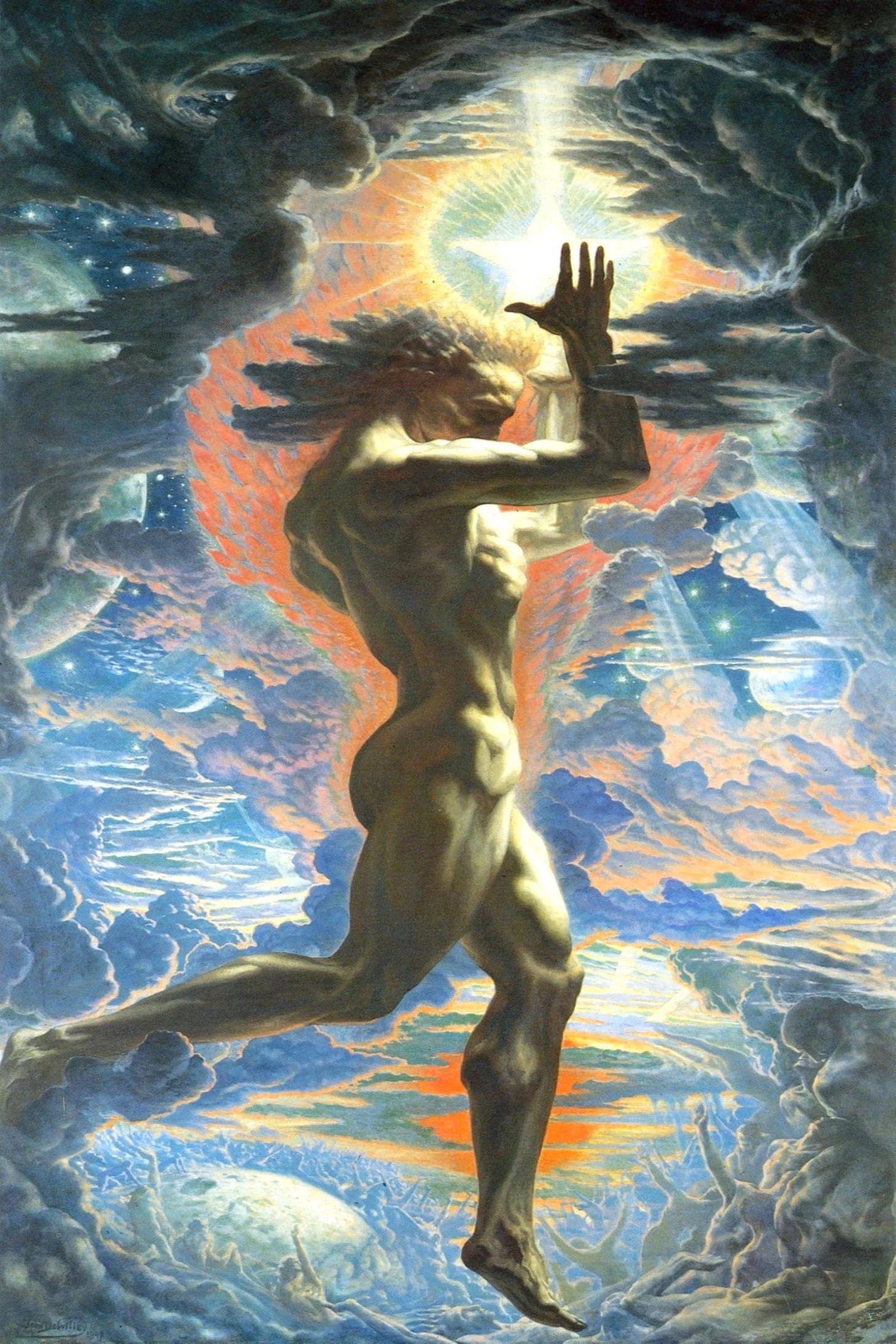

A defence of the German incel gamma male who tried to find an escape from the abyss

Nietzsche has been one of the many fracture points in right-wing culture, serving as a sort of shorthand for the divide between the various denominations of Christians on the one hand, and the loose agglomeration of pagans, vitalists, secularists, racist liberals, race-blind postliberals, antiwokes, and what have you, on the other.

This isn’t because most people on the non-Christian side have read Nietzsche. It’s impossible to know if they have or not, but, well most people don’t read, so it seems like a safe bet. What familiarity they have with Nietzsche is probably just whatever they’ve picked up from podcasts and the occasional YouTube video. That isn’t a slight on them, it just is what it is. The same critique applies to most Christians. How many have read the Bible? The whole thing? All 783,137 words of it? I’m guessing not many of you. Again, it is what it is.

Anyhow, it wouldn’t really be accurate to describe most of the non-Christian side as ‘Nietzscheans’, whatever that word is supposed to mean. Is Nietzscheanism an ideology? What are its tenets? Its core values? Its principles? Its programmatic plan of action? Does anyone know?

Now, as it happens, I have read Nietzsche, quite extensively in fact, albeit many moons ago, when as an edgy high school student I used to lounge on my bed with a copy of Beyond Good and Evil or The Geneology of Morals as Emperor blasted from my CD player. I read and re-read those books and many others, trying to understand them, trying to grasp Nietzsche’s worldview, his essence. Much of it was impenetrable at the time, as I was unfamiliar with the various philosophers, writers, artists, composers, and so forth that Nietzsche was in dialogue with, and these blank spots had to be filled in later. It’s been decades since I read Nietzsche, and I’ve forgotten a great deal about him; my Nietzsche is very rusty. Nevertheless, with all those caveats, I’m going to offer my take on the man, for whatever little it is worth.

Reading Nietzsche was not easy, and not only in terms of parsing the text. I don’t think I’ve ever had as much trouble reading an author in peace as I have with Nietzsche. My grandfather, who I don’t think had ever deigned to comment on my choice of reading material before, gravely remarked, “The Nazis liked him,” with a tone of deep distrust and disapproval (he doesn’t like Nazis very much, and isn’t so sure about Germans in general). “Yeah but so did everyone back then,” I replied, “Besides they didn’t understand him.” Not that I necessarily understood him all that well myself, but I could state with authority that the Nazis definitely didn’t, because most of the editions I was reading were those translated by the Jewish academic Walter Kauffman, whose incessant footnotes badgered away at me with florid excuses for Nietzsche’s misogyny and racism or whatever other sin he’d committed against Kauffman’s liberal sensibilities as I tried to just read the damn book.

Later, for a high school English presentation on the Greek chorus, I based my discussion on Nietzsche’s treatment of the Birth of Tragedy from the Dionysian cultic rituals that developed into the chorus and, thence, into Greek drama. The theatre kids loved it, but the teacher, a nice liberal lady who disapproved of Nietzsche, and who was also feuding with me, gave me a 0, proclaiming primly that I had not limited myself specifically to the chorus in Oedipus Rex, which was the object of study.

On another occasion I brought a copy of the Geneology of Morals to the barracks for some light reading during whatever down time we might get during a summer artillery training course. On the first night this nearly resulted in a fist fight with a Christian farmboy from a different regiment, who tried to confiscate it from me on the grounds that Nietzsche was Satanic. He relented when I made it clear to him that, yes, I would fight him, if he wanted. We ended up getting along pretty well. As it turned out I didn’t get much reading done. We did not get much down time, and what we did get I mostly spent drinking.

None of this has ever happened to me with any other author.

Nietzsche seems to elicit either frothing anger or dismissive contempt amongst Christians. This is understandable. He did after all write a book called The Antichrist, and coined such memorable phrases as God is dead. Characterizing Christianity as a form of slave morality doesn’t endear him to Christians either. As to the contemptuous dismissal, this is usually phrased along the lines that Nietzsche spent the last decade of his life as a catatonic madman, probably due to advanced syphilis, and that his life before this was marked by professional and social failure, continuous health problems such as severe migraines and painful digestive issues, and rejection by romantic interests. This “Ubermensch”, they say, was a loser. He was an incel. He was a gamma male.

If you aren’t familiar with

’s sociosexual hierarchy, you can find the definition of its categories at his Sigma Game Substack (which you should absolutely subscribe to) here. Briefly, the SSH classifies men (and only men) according to the ways they relate to one another, and therefore (since women are exquisitely socially sensitive), to women. It divides men into the following categories: alphas, the natural leaders who get most of the female attention; betas or bravos, who are not Pyjama Boy, but rather the alpha’s lieutenants and capos, enforcing the alpha’s rule and getting some of the female attention that spills out of his penumbra; gammas, who are essentially low-t nerds with poor social skills that scare the hoes; deltas, who are basically the workers, the ordinary joes who keep everything running, and are sometimes after much struggle successful in landing a waifu; omegas, who are at the bottom of the hierarchy, neither receiving much from it nor contributing anything to it, and never leave their dirty basements; sigmas, who are essentially lone wolves with an ambivalent relationship to the hierarchy, which they don’t really care about (they have their own, more interesting thing they’re doing, which they’re happy to do alone if necessary), but nevertheless do quite well within it, often challenging the alpha’s authority without intending to; and lambdas, who exist outside of the sociosexual hierarchy because they are literally gay.If you want an image of the SSH, consider your typical American high-school in the 1980s. The alpha is the captain of the football team; the betas are the other football team players; the gammas are the chess club nerds; the deltas are the normal kids with nothing much remarkable about them; the sigma is the kid in the metal shirt who cuts class because it bores him and then shows up at the party with a hot girl from a different school that no one has met before; the omegas are the dropout welfare trash kids; and the lambdas are the theatre kids.

So, was Nietzsche a gamma male incel? Was he a loser and a nerd?

Of course he was. Vox is absolutely correct about this.

Christians will usually follow up the gamma male incel attack by noting the absurd contrast between Nietzsche’s lived reality, as a frail neurasthenic with a terminal case of oneitis who could be sent into days of migraines by a chance encounter with a caffeinated beverage, and the concept of the Ubermensch he preached in his writings, most notably in his very strange novel? prose poem? mental breakdown? Thus Spake Zarathustra. By the same token we might note that Virgil was no Aeneas. The character created by the artist is not the artist; if the artist was the character, he’d be too busy running around doing heroic character things, not hunched over in his scriptorium scribbling away with ink-stained fingers.

And make no mistake about it – Nietzsche was as much the poet as the philosopher, indeed, probably more poet than philosopher. One of the most common complaints you’ll hear about Nietzsche is that it’s not at all clear, much of the time, what he’s getting at. What is the actual argument here? people will ask. They’re used to philosophers whose turgid prose is a loose string of logical syllogisms, composed with all the charm of a mathematical derivation. The wild electricity of Nietzsche’s divine madness is an entirely different genre.

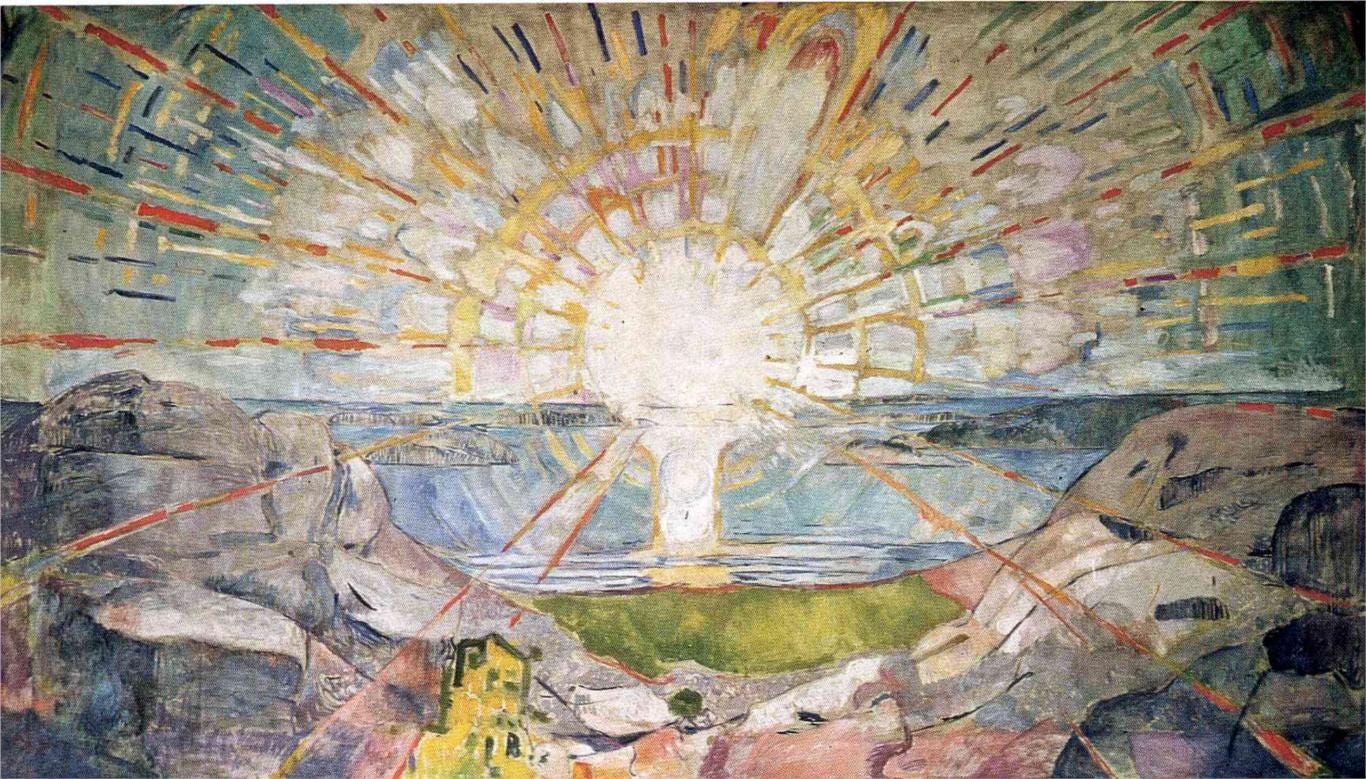

We call Nietzsche a philosopher because that’s the closest category we have to throw him in, but this is a poor categorization. Nietzsche’s mind – and yes, this may well be because it was broken by syphilis – did not proceed according to the narrow rails enforced by a rigid adherence to logic and reason. It was not weighed down by the gravity of methodological rigour. That is not to say that he did not apply reason, simply that he was not limited to it. He made use of revelation, of inspiration, just as much. He felt as much as he thought when he wrote, inhabiting the ideas he developed with his passion as much as his intellect. He thought with his whole brain, using both his left hemisphere and his right – in Nietzsche’s language, the Apollonian and the Dionysian. Being aware that philosophy specifically, and Western thought more generally, was to an extraordinary and even pathological degree locked into the left-hemisphere mode, into the Apollonian realm of rational dialectic, he went out of his way to cultivate the Dionysian instead, to get into touch with his intuitive, subconscious, ‘irrational’ mind. As much as Nietzsche was a philosopher, he was also an artist, a poet1, a mystic, and even, dare I say it, a prophet.

None of which is to say that he was not also a giant loser.

But then, most philosophers are nerds who are bad with the ladies. There are exceptions, of course. There is no record of Plato being bad with the ladies; Plato’s tastes are reputed to have run in different directions.

Vox’s characterization of gamma males usually includes the idea that they live in delusion bubbles. Being somewhat clever, they often think they should be in charge. That they are very obviously not in charge is a painful reality. Being verbally astute, they then proceed to resolve the cognitive dissonance by building glorious castles in the mind, in which they are the ‘secret king’ as Vox puts it: despite what your eyes might tell you, the gamma knows that actually everyone really respects the gamma, the girls all adore him, and when he ran away from the laughing alpha and his hooting bravos with tears in his eyes, what really happened was that he won the moral victory. While the delusion bubble insulates the gamma’s emotional life against harsh reality, it also makes it effectively impossible for the gamma to recognize and change his behaviour. The gamma is characterized by an almost total lack of self-awareness, which in turn leads to his having almost no insight into the character of others. For example, in the gamma’s relations with the fairer sex, he tends to lean hard into the Madonna/whore dichotomy, pedestalizing the object of his affections as an idealized, perfect, saintly, wonderful creature for whom he is of course the perfect chevalier blanc ... right up until she rejects him, at which point she becomes a foul, vile, treacherous temptress, a succubus straight from the rotten heart of hell. Girls tend to intuit this, which is one of the reasons the gamma is kept at arm’s length.

This is one point where I don’t think Nietzsche really matches the gamma ‘ideal’. Far from living in a delusion bubble, Nietzsche was deeply, even painfully psychologically insightful.

When considering other thinkers, Nietzsche did not only, or even necessarily primarily, look at their ideas. He looked also at the men who produced them, at their character, at their very biology. He considered that a great deal of human thought was only superficially rational, that it was indeed mostly rationalization, often of naked self-interest. In other cases self-interest might not apply, and a man’s thoughts might be instead an unconscious manifestation of ill health, poor sleep, bad digestion, or too much time spent indoors. In other cases still they might be an outgrowth of exuberance, of vital creative energy, of an abundance of life and spirit. One’s thought, Nietzsche suggested, was not a purely mental construct: it was also a thing of the body, and a diseased body would invariably bias the thought that it produced towards disease.

Nietzsche did not arrive at this view because he was the very picture of the well-turned-out, healthy specimen, but precisely because he knew that he was botched: physically weak, sickly, prone to long bouts of painful illness. He observed the effects of this frailty and pain on his own mind. He’d spent his entire life observing them. Many of the symptoms he struggled with, the migraines and nausea that afflicted him, the long bouts of depression, the blindness that would suddenly strike him, had done so since he was a boy. His father, a Lutheran minister, suffered similarly, and died at 36, even younger than his son. He had a brother, who was also sickly, and died at the age of two, shortly after their father. Young Friedrich was not even five, and yes, after that, he was raised as you might expect in a household of women. While Nietzsche’s syphilis was confirmed at autopsy, the early onset of his symptoms and the similar ill health that killed the other men in his family argue that it was probably not the only disease that plagued him. Nietzsche’s body was a curse all his life.

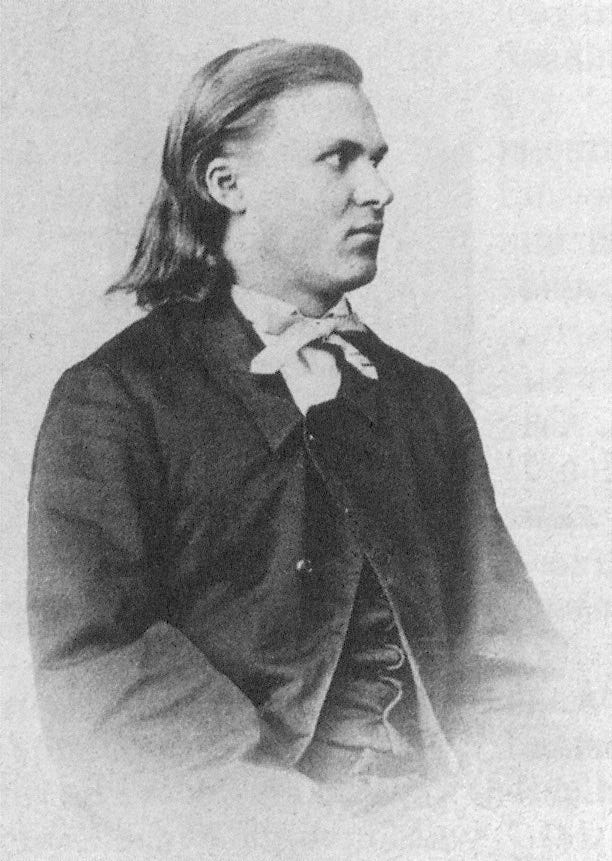

This is not to say that Nietzsche was entirely ill-favoured. He was a promising student, fluent in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and French, in addition to his native German. Originally aiming to become a minister like his father, he switched from theology to philology after losing his faith. At 24 he became the youngest tenured professor of classical philology in history at the University of Basil, despite not having actually completed his doctoral dissertation, which he likely found too boring to be a good use of what limited productive time his health allowed him. Before this he volunteered for the Prussian artillery, where he was reckoned a competent enough soldier and a good prospect for rapid promotion, but an injury sustained in a riding accident put an end to this ambition. Despite this, he again volunteered to serve as a medical orderly in the Franco-Prussian war.

Nietzsche would have laughed out loud at the suggestion that he thought of himself as the ubermensch, which he emphasized time and again was an ambition, an ideal, rather than an actuality. The ubermensch is as far from man as man is from ape, and Nietzsche knew full well that he too was more ape than man, and a particularly wretched example of an ape at that. An ubermensch could only be produced by a continuous and long-sustained process of self-overcoming, of continuously pushing through limitations to become more than one was before.

That is not to say, however, that Nietzsche did not apply a personal praxis based upon his philosophy. To not do so renders any philosopher a hypocrite. In Nietzsche’s case, his particular problem in need of self-overcoming was his chronically ill health, the improvement of which he applied himself to all his adult life. Searching for ways to control his symptoms, he scrutinized his diet, removed himself to different climates, and went for long walks in order to ensure regular healthful exercise. When his madness struck he was in the habit of spending hours every day hiking the alps. Far from the dishevelled degen sprawled in the dregs of a dissolute lifestyle ranting drunken paeans to the Dionysian that one might easily imagine when reading him, in actuality Nietzsche was famously sober and abstemious, with a quiet and unfailingly polite disposition.

Nietzsche wrote extensively about his efforts to improve his health, of what worked and what did not, which foods were okay and which invariably produced some form of distemper, all from the point of view of how such factors affected his thought. He was trying to be as ruthlessly honest as he could in his evaluations, and first of all he had to apply those evaluations to himself, to ask in what ways his own biology affected the tenor of his own thought. If Nietzsche were to be told that he was a gamma male and an incel, after the terms had been explained to him he would nod sharply and agree with you.

This almost morbid preoccupation with all of the myriad ways in which biology affects thought led Nietzsche to his great insight regarding the different types of morality favoured by masters and slaves. The biological circumstances of the two groups are very different. The master is classically the recipient of eugenic breeding, the beneficiary of regular healthful exercise, and is raised on good food, and is therefore tall, strong, healthy, beautiful – noble. The genetics of the slave, by contrast, might come from anywhere, with no particular regard to breeding; the slave does not exercise, but is stooped in forced labour; the slave eats whatever scraps are available. The slave therefore is usually visualized as short, weak, sick, ugly – wretched.

Of course two such entirely differently polarized types of people are going to have fundamentally different understandings of morality. They will justify what is good for them, while ranging from benevolent through indifferent to actively hostile to the good of those who are not like them. In every case, the morality professed by any given human type is simply the expression of that type’s will to power, channelling itself into the available outlets.

While Nietzsche would doubtless agree that he fulfilled the criteria for an incel gamma male, he might also go on to observe that the properties of the sociosexual hierarchy’s alpha and gamma, and the dynamic this creates between them, are all really quite reminiscent of the correspondences between the master and priestly type in his own system of thought. On the one hand, the effortlessly dominant, attractive, gifted, and popular man, who is used to being obeyed without question. On the other, the weak and craven man, who is nevertheless verbally and intellectually gifted, whose will to power is warped by a lifetime of festering ressentiment distilled from an endless, steady drip of humiliations, rejections, and defeats at the hands of his obvious superiors. The will to power of the alpha, the master, the captain of the football team, the warlord, is effortlessly fulfilled, and therefore takes on an open, honest, trustworthy, reliable character; that of the gamma, the slave, the priest, the nerd, the reject, can only satisfy itself in hidden and secret ways, and must therefore become crafty and treacherous, a kind of poison.

Nietzsche observed that Christianity had clearly emerged from the morality of slaves. It first spread through Roman society through its slaves. Its gradual insertion into the public life of the upper classes furthermore came largely through the vector of its women, who are in relation to men, in essentially every human society, in a position of weakness, which is to say the position of the slave, and therefore must adopt the corresponding moral strategy. Given all of this, one would expect that Christianity would be a type of slave morality, and Nietzsche pointed out exhaustive examples of this: the last shall be first; the meek shall inherit; the emphasis on charity, on care for the weak; the transvaluation of values, which all that was healthy, strong, and manly – good – in the pagan conception of virtue became identified with the Christian concept of ‘evil’, whereas all that was low, mean, and contemptible to the pagans became identified with the Christian concept of ‘good’.

Masters do not tend to concern themselves to a great degree with the opinions or beliefs of their slaves. Slaves are property, a kind of object. So long as slaves do as they are told, perform the functions assigned to them, obey the rules of the house, and are appropriately respectful, they don’t need to be beaten or executed, and can therefore be ignored. Slaves on the other hand must maintain at all times a high degree of awareness of their masters, understanding the master’s psychology and habits well enough to anticipate them. The slave must model the mind of the master to a degree that the master is not obligated to model the mind of the slave. This makes the slave wily and cunning, which is the slave’s great strength. It is often thought that Nietzsche was drawing a value distinction between slave and master morality, and this is a very easy thing to misunderstand, especially as he certainly had his own aesthetic preferences. He was not saying, however, that slave morality is an intrinsically bad thing, that it is necessarily wicked or contemptible or evil. It is simply a blunt assessment formed by closely observing the sociological conditions of Roman society, the matrix from which Christianity emerged: the morality of the free man who may own slaves versus the morality of the owned, each of necessity what they are. In and of themselves neither are good or bad, though each has its definitions of both.

Indeed, Nietzsche gave slave morality its due. It was through slave morality, Nietzsche said, that the human soul acquired depth. The repression of natural drives into hidden places, the requirement to get inside the head of the master, to understand what made him tick ... all of this excavated secret tunnels and chambers within the human soul, creating within it an entire subterranean world.

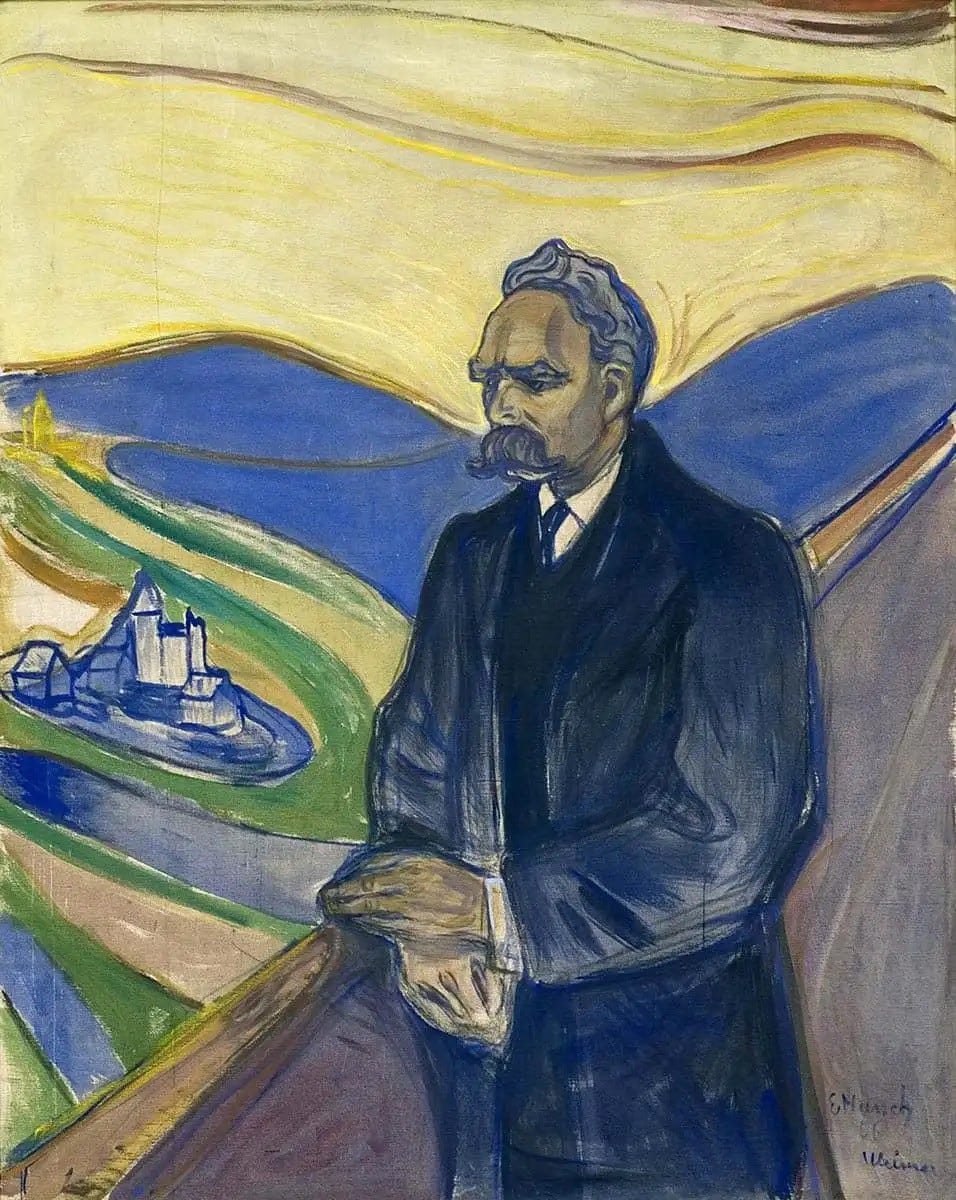

When Nietzsche famously pronounced the death of God, this was not a shout of triumph, but a howl of despair. God, Nietzsche understood quite well, was what underlay the absoluteness of being, of truth, and ultimately of morality. Without Him there are no assurances, and everything becomes contingent and relative. From this perspective one can look at the different moralities of different peoples, in the context of the different human types that produced them, and understand these moralities as simply ‘what is good for this group to do’. This is useful, but ultimately it is all a great chaos, a shifting sea of relative moralities, and as one’s perspective widens out one finds oneself staring into the howling blackness of the nihilistic abyss. Nietzsche forced himself to look at that abyss, to stare at it, for much longer than is healthy.

Psst, you. Yeah, you. The one reading this. I don’t suppose you’d be interested in supporting this blog? I put a lot of work into this thing, you know. Yesterday I spent the entire afternoon just looking for art. It’s a bit ridiculous. Composing and editing eight-thousand-word text walls about dead philosopher-poets doesn’t happen overnight. Anyhow, I COULD put this behind a paywall, starting here, halfway through, when I’m pretty sure your attention is hooked or you wouldn’t have gotten this far. So just think how annoyed you’d be if you got here, where I haven’t even gotten to the good stuff yet, and encountered a damn paywall. Pretty annoyed I bet. Good thing it isn’t there.

But staring into the abyss of my finances is a frightening thing, let me tell you.

Nietzsche did not kill God by announcing His death. It was a simple acknowledgement of the reigning social reality. The churches still stood, and people continued to worship, in Nietzsche’s time as now, but this was no more than habit. He saw that inside the scientific worldview that had emerged from the Enlightenment, there was no possible room for God. He was not the first to observe this: whatever the private beliefs of any given scientist, scientific progress is usually achieved by assuming that a given phenomenon is not caused by divine intervention, and then testing different possible non-divine explanations. This worldview in which God is simply irrelevant, in which it does not matter what you believe at all so long as you perform your function for the world-machine, which is above all to treat the world as a machine, had in Nietzsche’s time already long since conquered the commanding heights of society. It was only a matter of time before that same worldview would work its way through every human institution, seeping through the consciousness of the masses until it permeated everything, dissolving the Christian world in its wake.

Without God, the abyss. Does this not describe how society has felt since the onset of the twentieth century? Like we have all been perched on the edge of nothingness, growing gradually more deranged as the horror of the void eats away at our collective soul? The pointless industrial blood feasts of the World Wars; the yawning risk of immanent extinction over disagreements regarding industrial management policies that followed the cracking of the atom; the Dionysian revels for no other reason than to revel with abandon which started with jazz, and then grew into rock and roll and hip hop and raves ... each of these has the stink of nihilistic horror about it, either as consequence or coping mechanism.

The abyss, Nietzsche knew from experience, would drive men mad, and he was absolutely correct in this diagnosis. Just look around at clown world today, when the disease is advanced to a degree that would have shocked even us a mere decade ago. Nietzsche saw this coming, just as he saw that music would become more Dionysian, more wild and free and carnal, as the next century wore on. I’ve often thought that it would be fun to bring Nietzsche to a rave, show him people blissed out of their minds on MDMA dancing like Maenads to psy trance.

He’d almost certainly hate it, complain of a headache, and demand to leave immediately. He would furthermore probably be troubled, because the Dionysian revels, together with everything else he would see in clown world, would merely demonstrate that we had not, in fact, fought our way through the abyss of nihilism – that we were still firmly in its grip, and had spiralled down into it to a perilous depth. This would probably have depressed him greatly.

Far from preaching nihilism, Nietzsche wanted to find an answer to nihilism, a way to say, as he would put it, Yes to life, which is hard to say when God is not a permitted answer. The answer he settled on was the program of the ubermensch: of producing higher types of man, of making this perfection of the human, of becoming more human than human, the moral goal which gives existence meaning. If one accepts as axiomatic Nietzsche’s position that God Is Dead, the logic of the ubermensch is almost inescapable, and seductive: meaning comes from God; but God is merely a phantasm of the mind of man; therefore to reestablish meaning in the world, Man must put himself into the place of God, becoming his own creator, his own judge, his own goal.

This was not necessarily an original concept, as it is remarkably similar to the driving impulse of the Hellenistic society with which he was so familiar, in which the goal of men was to become as gods. Almost the least of them were assured of this in a small way, if they sired a son who burnt offerings at the family altar to the ancestral gods of the hearth, and their son sired a son in turn. The greatest became Perseus, Theseus, Hercules, Achilles, Alexander, Caesar: made heroes and even actual deities in death, with sacrifices burnt to feed their spirits and hymns sung to the glory of their names. The Nietzschean program of the Ubermensch is really a call to revive this Classical heritage – not the philosophical heritage of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, which Nietzsche considered mere symptoms of decadence, but the earlier model of the archaic, heroic age, when men still had healthy instincts, when they were full of life.

Nietzsche left his ubermensch vaguely defined, and the work in which it is discussed most extensively, Thus Spake Zarathustra, is widely believed to be the work most resembling the fevered ravings of a madman slipping ever closer to the edge of irreversible psychosis, as he in fact did a few years after completing it. Whatever other congenital illness of blood or brain that Nietzsche had managed to temper with his careful lifestyle, the syphilis was there too, eating away at his neural tissues, removing his inhibitions.

Thus Spake Zarathustra was a marked departure in style and content from the comparatively calm and reasoned philosophical treatises he was known for. Zarathustra was the name of the prophet of Zoroastrianism, the monotheistic ur-faith that many believe to be the original model on which all further forms of priestly rule were based, and Nietzsche certainly knew all of this quite well. This book is not, however, a discussion of Zoroastrianism. Zarathustra has instead come to correct his Bronze Age error, and to herald the arrival of the ubermensch. The book is written in Zarathustra’s voice, and largely consists of Zarathustra’s monologues and dialogues as he observes the wretched state of humanity, extols the ubermensch, and preaches it to those who cannot or will not hear. It is not quite a story, without any particular plotline. The language is entirely figurative, allegorical, and metaphoric, and it is therefore not always at all clear what Zarathustra means.

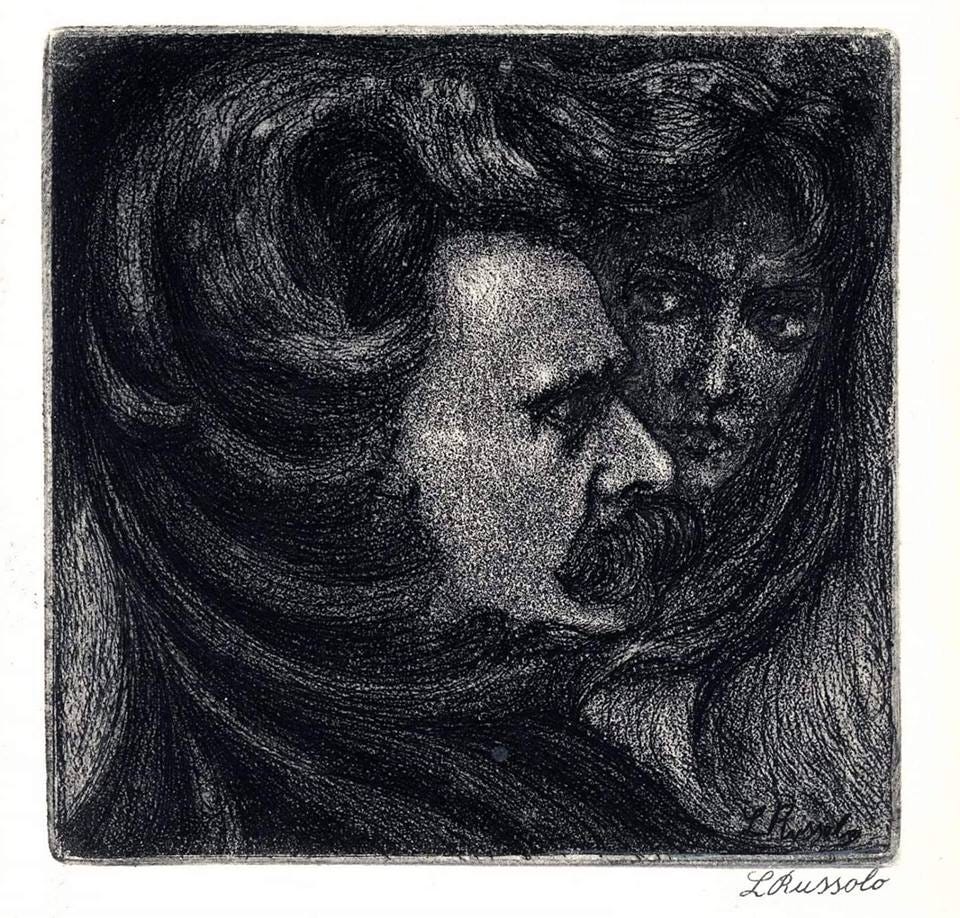

Nietzsche liked a good turn of phrase, indeed the playful vigour of his language is one of the chief delights of reading him, but Thus Spake Zarathustra is written entirely in a poetic mode. It moreover has a relentless intensity, a demonic forcefulness to it. There’s no question that when Nietzsche was writing it, he was seized by some great passion, some mania that refused to let him go. Many artists throughout the millennia have described exactly this state of possession, as artists do to this day. Indeed in ancient times it was commonly believed by artists that when they were in the throes of some great creation that it was not they who were creating at all, but a literal spirit, a demon or genius that took control of them, only to leave them exhausted and drained when it has done its work.

Nietzsche’s subsequent works – in particular Beyond Good and Evil, The Genealogy of Morals, The Twilight of the Idols, and The Antichrist – were largely an attempt to explain and develop the concepts of Thus Spake Zarathustra. Four years after Zarathustra’s final volume was published, Nietzsche had the most productive year of his life ... and then abruptly descended into terminal madness, throwing his arms around a horse to protect it from being whipped, before collapsing on the ground.

When Nietzsche’s mind died he was still young, alone, impoverished, and unknown. He died a hollow shell, after eleven ignominious years as an invalid. He was an utter failure by every conceivable material or social metric, one whose death came as a mercy.

Yet the spirit he brought across, whose voice spoke through his pen as Zarathustra, leapt from those pages into the minds of thousands of people, and those people remade the world.

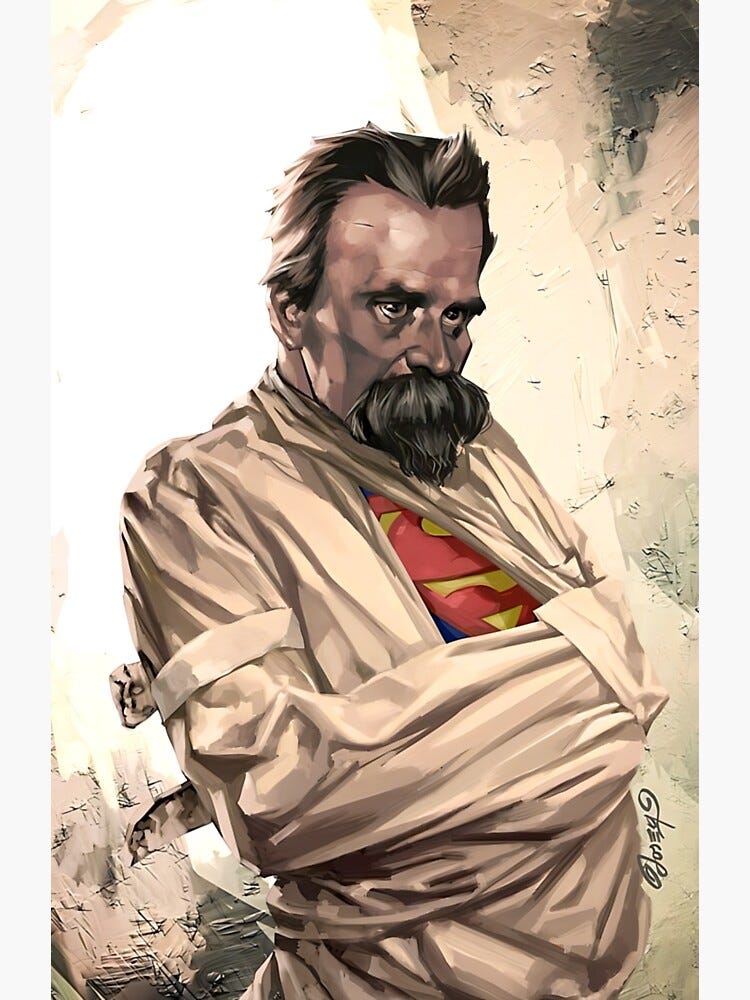

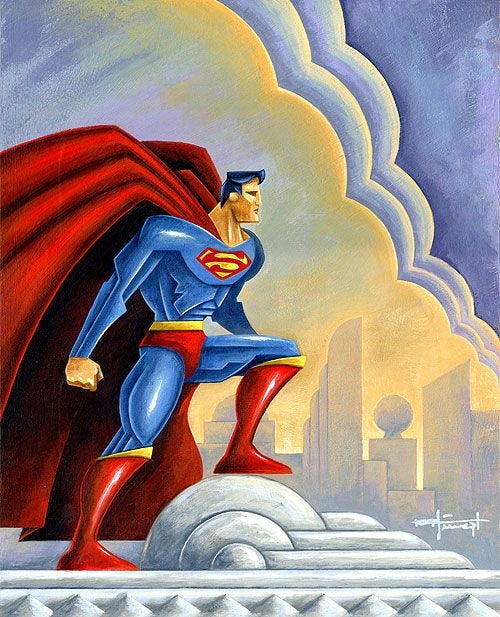

The early twentieth century was the era of Nietzsche’s triumph. Art nouveau, art deco, expressionism, cubism, futurism, surrealism, and jazz all carried with them a Dionysian spirit, a sense of wild freedom, a tossing loose of structure and constraint, an eager grasping after new possibilities. In literature we see the rise of the rock-jawed Captain-Doctor Danger archetype, with an eyepatch, a zepellin, and a death ray, both a brilliant man of science and a bold man of action. This type, adapted through endless variations across the genres of adventure fiction, is quite clearly a representation or vulgarization of the ubermensch, and of course his most powerful version is universally known to be Superman, which is just another way of saying Ubermensch. This is all but explicit in the works of Ayn Rand, whose Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged are hymns to the emancipation of ubermenschen, for all that her philosophy of Objectivism explicitly repudiated Nietzsche’s irrationalism.

In public policy, eugenics was seen as basic common sense not only in Nazi Germany but across the civilized world, and what was eugenics but a biological program for the production of ubermenschen? You see this same spirit across many of the civic projects of the progressives of the early twentieth century. Progressives at the time were far more likely to be of the right-wing variety, more vigorous and active and optimistic. In the heady, early days of scientific managerialism, a great deal of the motivation for public health projects, or for attempts to refine and universalize access to pedagogical techniques, was that this would lead to the production of healthier, stronger, more intelligent people. To produce the ubermensch, one must first prepare a people who are capable of producing him – this can happen only by raising them up as well. As for those doing the hard work of making these projects real, of building these institutions and then using them to mould the public – was this not precisely what the ubermenschen, who are both more spiritually as well as intellectually and physically developed, would do?

It all went to shit in World War Two, which broke not just the world but also Nietzsche’s answer to the problem of nihilism. It wasn’t only the clear fondness of fascists and national socialists for his work (which for the Germans at least went back to World War One when they carried copies of Thus Spake Zarathustra with them at the front). Nazi eugenics certainly put an end to the project of breeding a biological ubermensch, but that war was also the era in which the twentieth century’s great dictators – Stalin, Mao, Mussolini, and Hitler, and all the others stamped in their mould – arose.

It’s unlikely that all of these men were inspired directly by Nietzsche, in the sense that they read his works and decided that they would make themselves the ubermensch. Hitler certainly did read Nietzsche, though I’ve heard he had his criticisms. The comparison to the great dictators also does some violence to Nietzsche’s conception of the ubermensch, which was certainly not only a political phenomenon or even primarily a political phenomenon. The dictators were however produced by a society in which the concept of the ubermensch was so influential that it had already practically faded into the background as a sort of trope, in which so many people were thinking about it, writing about it, imagining it, drawing it, and working to bring it about in the real world, that it could not help but have a manifestation on the political plane as well.

These men rose to become as gods within their countries. They are gods to this day, their memory rendered ineradicable by the shadow their lives left on history. To cross them was death. Their rule was absolute in ways the rule of kings had never been. Their faces covered their lands in billboards ten stories tall, and their clumsy hands proceeded to reshape those lands from the top down in their own image, with disastrous results. All of these men, and Hitler especially, are regarded by moderns with horror, for each of them left devastation behind him. Thus we lost our taste for the political ubermenschen, and at the same time, in the ashes of the same war, developed an aversion to biological ubermenschen.

For decades all talk of eugenics was silenced everywhere but in science fiction novels, while politics began to be shaped with the intention of preventing new Hitlers from arising by any means necessary. Power was diffused as far as possible throughout the managerial structure, so as to make it impossible for any one man to gain enough influence to flip the chessboard. Meanwhile, the new institutions that had been built by the early twentieth century’s right-wing progressives went to work on the surrounding society, remoulding it through the educational system and, as the MKUltra generation grew up, through workplace regulatory systems introduced via the Civil Rights system, all with the goal, not of producing ubermenschen, but of preventing them.

Insofar as it was the Nietzschean current running through society that inspired the rise of the great dictators, those currents had to be suppressed. The whole project of producing the ubermensch had to be cancelled. At the same time the factors that enabled the production of an ubermensch had to be curtailed, which ultimately resulted in a total restructuring of society. All those new institutions that had been built by right-wing progressives to uplift the masses, to educate and train them to high intellectual and physical standards for example, were gradually repurposed by left-wing progressives into institutions for the prevention of Hitlers. One of the best ways to do this is to make sure that the graduates, especially the white males (judged most likely to become Hitlers), are as unfit, untrained, weak, incapable, ignorant, and neurotic as possible. Over many decades the schools have gradually become institutes of exquisitely refined psychological tortures designed to do just that on an industrial scale.

An equally inspiring alternative had to be provided to replace the ubermensch. The alternative ideal they came up with is essentially that illustrated by the Star Trek future: an amiable multicultural society with magic technology that makes life easy and exciting. It’s no accident that Kirk’s nemesis Khan is an ubermensch of both the genetically engineered and the political kind; predictably, the result of his rule is a nuclear war, in the ruins of which the society that became the Federation was born.

Star Trek’s Federation is not only a human endeavour. It’s membership is open to any friendly species, and indeed the Federation seems to proseltyize, with one of Star Fleet’s functions being as a missionary organization, to actively look for and recruit uncontacted species. The Federation (read the United Nations) wants to convert your species, it goes out of its way to make friends, and through this humans (read white Americans) come to play an important role in a galaxy (planet) full of friendly aliens (weird foreign people). Naturally, the humans are portrayed as multicultural right from the start, the implication being that getting along with one another across every boundary of colour and creed lays the necessary psychological and moral foundations for a galactic empire. Diversity is our strength!

That Star Trek ideal is souring in the era of hypermigration and economic stagnation. It turns out aliens aren’t always friendly, that some of their differences go beyond the merely cosmetic, and meanwhile the electronic doodads – the communicators (cell phones), computers, touch screens, holodecks (computer games) and so forth – just don’t hit the dopamine like they used to.

From a Nietzschean perspective, clown world is just slave morality gone absolutely feral. The whole ubermensch project is, of course, bound up with master morality: an ubermensch must be the master of himself, and if he is truly an ubermensch he will effortlessly master others. To impose a eugenic vector upon society for the biological production of an ubermensch is necessarily also to master society. The two are inextricable. It follows that the abandonment of the ubermensch project, our deliberate turning of our backs upon it and heading in another direction, must of necessity encourage its moral opposite, which is to say slave morality.

If Nietzsche is correct about Christianity also being the product of slave morality, that means that the Woke church must destroy its rival. You can’t have two religions occupying the same cognitive space. This is why the woke hate Christianity so much, and always attack it, despite Christianity being no threat to the woke church of no salvation – not that Christians are necessarily friendly towards wokeness, simply that the churches have been rendered politically toothless. If one wanted to be unkind, one could say that it is the narcissism of small differences, but this would be deeply unfair because the differences in their fruits are simply vast. Christianity may be a slave morality but it is slave morality redeemed, the simple proof of which is that its fruits must surely be judged to be largely good ones, to a greater degree than can be said about any other religion. Wokeness, being a nihilistic faith, does not even believe in redemption, for itself or anything else, and therefore has nothing whatsoever to redeem it.

If pursuing the path of the ubermensch led to horrors, the opposite movement produces terrors of its own. It is as though we have become determined to reduce humans to the lowest types possible, encouraging them in all their worst habits while discouraging, frustrating, and punishing every ambition. Reading is discouraged. Exercise is shamed. Indulgence is enabled. It goes without saying that the food is poisoned. Emotional dependencies on drugs and therapists is encouraged. Dysgenic breeding is modelled in the entertainments. It is, of course, possible to cut across all these threads in one’s own life, but the overall effects on the population are plain to see: IQs falling, eyes dulling, waists expanding ... over time people have sagged into exhausted, ugly parodies of humanity, sapped of all vitality and vigour. Ugliness and exhaustion reigns.

We have reached the point at which this broad and deep degradation of humanity has begun to produce in a great many people an overpowering nausea, to the degree that they can endure it no further and must find some kind of escape. For many this means that they must work individually on themselves, to counteract the effects of this multilevel assault on the bodies, minds, spirits, and souls. Some become more militant in their opposition to the entropic pull, and seek to undermine and overthrow its dark power over the public mind, to burn it out root and branch.

We do not need to accept Nietzsche’s solution to the problem of nihilism, but it is a dangerous error to ignore his diagnosis. One way or the other, the nihilistic void that opens in the absence of God must be addressed, or it will consume us. Christians would observe that the surest resolution to this dilemma is to reintroduce God into our lives – to affirm that Nietzsche was wrong, that God is not dead, man did not create God but God fashioned man. Just stop staring at the abyss, bro.

I think that Christians are fundamentally correct about this. The program of the ubermensch, of self-perfection for its own sake, of self-defined morality entirely uncoupled from any external frame of reference, unleashed nightmares. The reaction to this, the movement in the opposite direction, has become a nightmare of its own. Whether the goal be the betterment of the individual man or the amelioration of the misery of mankind, when pursued for its own sake, these goals produce abominations. We always go too far.

But I do not think that the answer is as simple as returning to the bosom of the holy mother church, either. The historiographical, archaeological, textual, geological, and astronomical discoveries of the scientific age that shattered Nietzsche’s faith, and the simple faith of so many others, cannot be undone ... not without the species giving itself a self-inflicted lobotomy. What has been learned cannot unlearned; what has been seen cannot be unseen. Naive innocence cannot be regained merely by wishing it so.

And yet the world desperately needs a Reenchantment.

In this, pagan and Christian share a similar task, but the work of the pagan is easier. Both must convince a skeptical world that magic is real, already a tall order, but the Christian must also convince the world that theirs is the Big Magic, the spell that rules all others. Their relationship may in the end be symbiotic, in that the pagans prepare the way for Christ’s return. But Christians must learn to coexist, to allow the lesser magics of the small-g gods to persist alongside their own. If they recapitulate their previous strategy of consigning everything that is not of the Bible to superstition, of wiping the lesser magics from the world, they will recreate the conditions that ultimately consigned their own faith to superstition.

Then, too, perhaps there is opportunity for a powerful creative tension to be drawn between Christianity and vitalism, paganism, whatever you want to call it. The two are surely irreconcilable opposites, but just as the opposite of one bad idea is another bad idea, it is also frequently paradoxically the case that the opposite of a truth is another truth. Before they deplore the vitalists, Christians would do well to ask what the attraction is ... and this is not a difficult question to answer. Mired in the enervation of an exhausted culture that is busy abolishing itself, a culture that worships the broken and venerates the hideous, a culture of life turned against life ... those who are nauseated by this do not want to turn against life. They want to live. They do not want to be meek, and gentle, like lambs. They want to be lions. They want to be strong. And then the German incel gamma male walks up to them, telling them that what does not kill them, makes them stronger, and that they are not dead yet, so.

Of course they respond to this. It is healthy and right that they do.

If Christianity at its core is slave morality redeemed, then what is master morality redeemed? Can we not draw upon both? One as armour and shield, the other as flaming sword?

Can we not remember who the real enemy is?

Thank you for reading this wall of text, which probably marks me out as an obvious gamma male. I don’t know, I don’t do self-diagnosis. In any case, as always seems to happen, this ended up being a lot longer than I expected, and honestly there’s still a whole lot more to say ... I didn’t even get into transhumanism, for example, which has pretty obvious Nietzschean overtones, though I think he would have disapproved. There isn’t much greatness in troons.

Anyhow, if you enjoyed this, you should

so you don’t miss whatever I write about next, whenever that happens to get published. My publication schedule is extremely undisciplined, just as my subject matter is extremely eclectic:

He published a volume of actual poetry, which wasn’t very good; he also dabbled in musical composition, which was even worse.

For me, Nietzsche is "the Last Christian", and every professed Christian who comes after him must first answer his critique. It is deeply humiliating as a Christian to recognise the power of his argument that ours is a slave religion and (worse) perhaps a slave morality. The deepest in faith would perhaps accept this and not be shamed by it, but not the laity. Nietzsche recognised that the brave spirit of the West had other sources, despite the attempts of elite ideology over hundreds of years to join together these strange bedfellows. Nietzsche is also the Last Christian because he stands at the end of moral time, at the abyss. He saw centuries ahead of his time and predicted the moral arc perfectly. Those who hate him from ignorance hear "God is Dead" as a shout of triumph, but (in my view anyway) it's really a scream of despair. But a prophet is always without honour, not least when he's painfully correct.

Hmmm. One of the central issues here is the utter lack of humility evinced by “secularists,” “modernists” .. People, like Nietzsche, who believe that “Darwin (science) has falsified the creation account in Genesis..” People whose minds and souls have been eaten away by rationalistic reductivism, crude empiricism, who think that debauched sybarite Hume was a genius.

The power of Christianity lies in paradox. You touch on the essence of the issue here: Nietzsche condemned the humility of God as “slave morality.” Calling poor Fred a gamma is precisely right, because his ethical imagination is basically that of an alienated teenaged boy raging against the social hierarchy of secondary school- it’s all about Apollonian beauty/power and Dionysian poetic hedonism for him, and he is using the exquisite intellectual power that he has (“I am so clever..”) to create and reinforce his own standing within that milieu. It’s all completely superficial, ultimately vapid, meaningless and stupid, and poor Fred knew it, which is definitely one of the reasons why he lost his mind in the end.

There is no such thing as an übermensch apart from Jesus Christ. No one else has ever claimed to be able to redeem us each, as an individual person, from death.. All the pagan titans, gods, heroes are tawdry simulacra of his manifestation of divinity in history. All of us, even the strongest, most beautiful, most intelligent, will decay, become stupid, weak, ugly, then die. Every trace of our existence will ultimately fade into the entropic penumbra of quantum death. There is no possible hope of individual transcendence of this howling void, no matter how valiantly we struggle against it.. We are each apportioned 120 years, no more.. Then..

What? What hope do we have? Is there any hope for the neuro atypical kid being bullied in the play ground? The Chinese worker drone being slaved to death 12 hours a day in that sweatshop? The addict derelict on the street, enslaved by his endocrine response?

The Nietzschean will sneer at these slaves with contempt. As his own paltry strength entropically fades, as he also withers away in time.

But maybe Christ’s inversion of worldly power is, in fact, real. Maybe the cruelty of this world is the true illusion. Maybe justice and mercy will in fact reign. May the infinite power of God is in the full service of goodness, joy, beauty and truth, and all of this not merely in the end.. But now, right now, amongst us here, today. Maybe willing the good of (loving) your enemies is the best and most effective way of defeating them, because maybe by willing the good of your enemies you might covert them to being your friends.. And maybe if this divine love we are called to show even the most recalcitrantly wicked is emphatically rejected, our love in the face of their evil might both sanctify us, as well as those who witness it, both now and in the end..

Maybe power and beauty are not truly material at all, and maybe Apollonian aesthetics are superficial; maybe Dionysian raptures are all ultimately vapid.. Maybe true beauty is transcendent, maybe the only true happiness is in the joy of self sacrifice, the emptying of oneself into the flame of eternal love..