Theft of Fire

A love story hidden in a hard science-fiction space adventure that asks hard questions about modern romance

Relations between the sexes may never have been as bleak as they are today.

The fuck rate has imploded. Boys are too terrified of girls to ask them out on a date, because ‘what’s the worst she can do?’ has devolved from the perennial answer of ‘reject you’, to ‘make your stupid face go viral on TikTok as the new embodiment of rape culture’. The modest upside of a fun night out is poor inducement for the life-ruining downside of permanent Internet infamy.

The Cold War of the Sexes is a trap of intractable mutual suspicion. Each of the armed camps regards the other without charity or sympathy. Every innocuous word is interpreted in the worst possible way. It’s a defect-defect game theoretic equilibrium where victory is obtained by shooting down, breaking up with, divorcing, or otherwise hurting the other party before they can do the same to you. The rules are simple. Never admit you’re interested. Never admit you have feelings. Always remember that every interaction is a transaction, every relationship is a power struggle – the goal is to keep the other in your debt, maintain a position of dominance, and never, ever, show weakness.

Pointing fingers is pointless. Men blame feminists, feminists blame men. Certainly the gynarchy has done much damage – the MeToo hysteria, Title IX star chambers, the emotional abusiveness of HR, kangaroo family courts, and all the rest. We all know the litany. On the other hand, men have spent a century failing every single shit test that feminists have thrown at them. There’s plenty of blame to go around. We’re all at fault for this. What matters is fixing it. The very future of our civilization turns on the question of whether or not it can be fixed.

Devon Eriksen’s debut novel Theft of Fire has a few things to say about that. Or, rather, show. In the best tradition of fiction, it does not tell, but shows: it is experiential, not didactic, demonstrating rather than explaining. The literary environment is saturated with big-brained, heavily footnoted polemics bemoaning the frozen wasteland of the modern sexual Niflheim. There’s not much more to say on the subject; it’s been mined out; everything that can be said, has been said by a thousand masculinity gurus, RedPill philosophy bros, cyborg theologians, and postliberal radfems.

And yet, the problem continues.

All those tracts, tweets, shitpoasts, essays, and diatribes are all just so much theory, and it’s clear Eriksen is familiar with that body of work.

Theory works for a few exceptional autists. Most, however, benefit from something more concrete, more personal, more visceral.

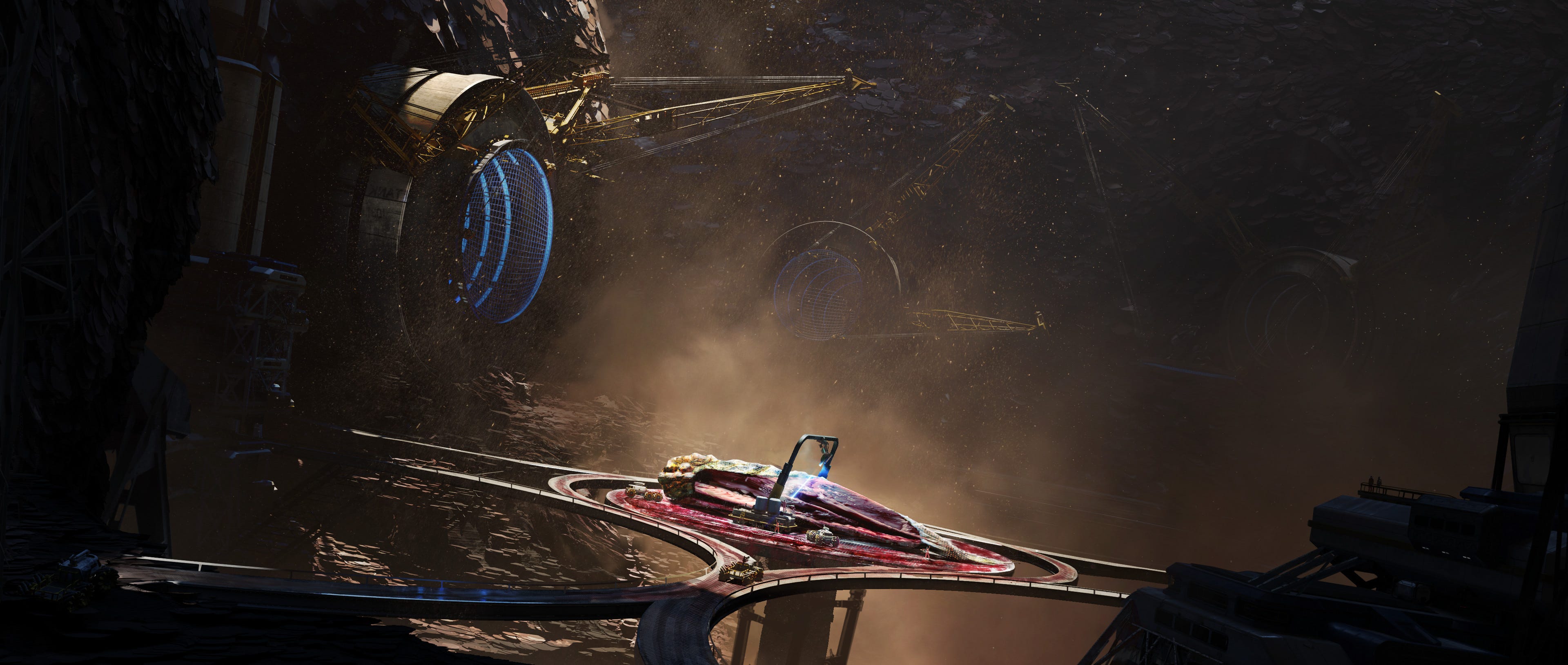

Theft of Fire makes for a strange vessel through which to illustrate the sexual predicament. On the surface, it’s a hard science-fiction orbital heist yarn. It is, I hasten to add, very good hard SF: it gets the science right. Devon Eriksen either has a technical background, or he’s done his research. There are no lazy howlers such as cometary ice storms posing a deadly threat out in the unthinkable emptiness of the Kuiper Belt1. The orbital dynamics are accurate. The nuts and bolts of space travel is convincingly portrayed. The variable pseudo-gravity from acceleration and rotation is used to excellent dramatic effect.

The science, however, is not the point.

The story is set entirely in the claustrophobic interior of the White Cat, the protagonist’s mining torchship. It opens when he walks onto the bridge to find it occupied by a woman who has hijacked his mining vessel by the simple expedient of buying his delinquent loans and locking his neural lace out of the vessel’s control systems, and who proceeds to press him into her service by blackmailing him, for mysterious reasons that she refuses to share even as she drags the hero and his ship to the edge of the frozen solar system.

The hero of the story is Marcus Warnoc, an asteroid miner turned pirate after a series of accidents leave him on the edge of bankruptcy. Marcus is a six-foot-something Belter with a cybernetic eye and a body made of corded muscle, a roughneck pilot perfectly at home in barhouse brawls, detonating explosives in asteroid craters to get at that sweet iridium cheddar and loosen up fist-sized impact diamonds, welding coolant manifolds in microgravity to get the fusion drive back online, and spending long months in isolation out in the deep black, contemplating the silent stars from the observation deck as he does heavy deadlifts to keep his body strong for those five-gee burns.

The hijacker is Dr. Miranda Foxgrove, heiress to the SpaceX dynasty, neuroscientist, and AI engineer. She’s somewhere around four feet tall – height being inversely associated with socioeconomic status in a world in which the proletariat spend their lives in microgravity, her parents had her genetically modified for shortness so that no one could possibly mistake her for one of the poors. Her genetwists don’t stop at height. She’s an IRL anime waifu, with violet eyes much too large for her face, an impossibly narrow waist, perfect curves, iridescent hair that shimmers like a butterfly’s wings, and bewitching pheremones that surround her in the perpetual scent of vanilla. Her body is a weapon aimed straight at the male libido. Miranda is also a budding sociopath, raised in the merciless gladiatorial pit of the bellum omnia contra omnes at the societal apex, in which friendship is for losers, trust is for suckers, and even your own family are out to get you.

Problem solving is at the core of every good hard science fiction narrative. The competent hero is presented with a series of dilemmas, which he must overcome by ascertaining the pertinent facts, taking an inventory of the available tools and environmental variables, and applying his rational, creative intellect to conceive and then implement a solution to the problem at hand. This is so central to classical hard SF that it is arguably the genre’s distinguishing feature, something that frequently seems to be overlooked in a market saturated with military SF where the solution is always ‘train harder, apply more firepower, and kill them first’, or the proliferation of deconstructionist postmodern narratives in which galactic empires are merely the scenic backdrop for discussion of pronouns over tea. Refreshingly, Theft of Fire gets the problem-solving right. The hero spends the novel applying his knowledge of physics, orbital mechanics, and engineering to problems of escalating difficulty. How can he figure out where his hijacked ship is being taken to, when he’s locked out of the nav computer? What the hell is inside the cargo container Miranda hid on his vessel, and how can he talk to it2? How can he disable the hijacker’s murderous security drones? How can he get control of his ship back? How can he survive Miranda’s crazy, half-baked scheme?

As technically competent as Marcus Warnoc is, the ultimate problem that he has to solve is not a technical, but human: the problem posed by the beautiful, brilliant, manipulative, borderline maniac that has seized his vessel and his life. He has to understand her psychology to grasp her motivations, and to do that he has to learn to see her as she really is, rather than the surface that she presents. In the process, however, he also has to learn to see himself as she sees him, and naturally this goes both ways While Marcus is the viewpoint character, it becomes clear as the novel progresses that Miranda is undergoing a reciprocal process: learning to see Marcus for who he really is, while at the same time coming to see herself as Marcus sees her.

Marcus and Miranda spend the first half of the novel trying to solve the problem of one another, in an opening sequence that veers between the funny and the brutish, held together by an undercurrent of sexual tension. Neither of them are particularly sentimental about the feelings of the other; both are comfortable employing deception and violence to get their way; each sees the other as an existential threat that, at best, can be tamed through force to follow their will. It’s as though two wild animals, each fantastically dangerous in their own way, each suffering from their own unique vulnerabilities, are locked in a cage for several weeks and set loose to claw at one another. I couldn’t help but wonder if the author was working through the emotional trauma of the lockdown period, when so many were trapped at home with significant others. Either one will kill the other, or....

Obviously, the story transitions to the ‘or’, otherwise there would be no more story. Ultimately, the two are forced by circumstance into an uneasy truce in which they must rely on one another to solve problems of a much greater magnitude than either poses to the other. The driving question becomes whether or not these two damaged, deeply suspicious personalities can learn to trust one another, which they will have to do in a world that is trying to kill them with extreme prejudice.

It’s rare for a hard science fiction novel to have a love story at the heart of it, and Theft of Fire would be thematically unique for this alone. It’s even rarer for a hard SF story to have this level of cultural relevance and psychological depth. The two main characters are archetypal of modern pathologies, without for a moment feeling like mere avatars. Marcus is the alienated, beaten down modern man: worried he isn’t half the man his father was, struggling with guilt for the things he’s done, struggling to avoid taking responsibility for the choices he’s made, angry at a relentlessly hostile world and deeply suspicious of the cold and unsympathetic powers who rule it. He’s the downwardly mobile, terminally online gymcel with a statue pfp. Miranda is the narcissistic girlboss with a trust fund, a million-follower Instagram account, and no IRL friends but a contact list crowded with frenemies, a manic-depressive pixie nightmare girl with a heart of iridium – more precious than gold, but brittle and easily broken.

There are no easy answers in Theft of Fire. The characters are damaged people, muddling through and trying to survive as best as they can, yet somehow, despite the odds, despite themselves, kicking and screaming the whole way, finding something like intimacy along the way. While the aesthetics couldn’t be more different, reading this I couldn’t help but be reminded of the thematic content of Samuel Finlay’s Breakfast With the Dirt Cult or

’s bittersweet Our Private Kingdom: romances written by male authors, exploring the broken, post-apocalyptic war zone of modern romance, and somehow finding bright rays of hope to keep struggling despite the disappointment and heartache.Theft of Fire is available as a paperback, hardcover, or Kindle edition via Amazon; other buying options can be found on the author’s web page. The author can be found on Xitter @Devon_Eriksen_.

A somewhat belated Merry Christmas to all of you! It’s been a couple weeks since my last post, for which I plead travel and the family commitments that come with the holidays. In between suffering through airports and Christmas crowds at shopping malls, I’ve been working on a longer piece, which I hope to publish before the New Year, but decided to prioritize this book review because I wanted to get it out while everyone’s Amazon gift cards are still fully charged.

P.S. the author didn’t ask me to write this; no money has changed hands; I am not getting paid for this review. I just really enjoyed the novel.

As always, in between writing on Substack you can find me on Twitter @martianwyrdlord, and I’m also pretty active at Telegrams From Barsoom.

I won’t name names, but recently threw a military SF book aside when it started leaning into that as a major plot point.

You might have noticed a third face on the cover, yet I discuss only two characters. Trying to avoid spoilers, here.

Devon doesn't have a Substack account so I'm just stepping in to say, thank you for this wonderful review!

To everyone who has bought copies, I'm certain you will enjoy it. Theft of Fire only published last month, and it has been such a wild ride. This is NOT a book that the traditional publishing industry would ever touch with a 10-foot pole, and it's too out-of-genre-spec to be picked up with a small press (who typically want "easy to define" novels, because that's what their readers expect. Theft of Fire is... well, I have read it 4 times, and I still have a hell of a time condensing the experience).

We're doing everything out of our home in nowhere, Tennessee, as Devon says, some of it ourselves, some of it hired out (cover art, editing). We're still in the "every sale counts" stage, so we're extremely grateful for everyone who's starved for good science fiction, who's read this post and taken a chance on a new author :) Devon wrote with one goal in mind: to give the reader something to love. And if you pick up his book, and if you find something to love, I'm encouraging you to tell a friend, or write your own substack post, because we're going at this alone, but we can't do this alone

Thanks again, and John, again, so glad you enjoyed. I was thrilled when you bought a copy. Now that you've read it, you see why the name of your substack amused me!!

OK, so Theft of Fire is a totes rad HARD SF novel with sexual tension released since the fall of Berlin Wall AKA a unicorn. And it's even not too expensive! Thank you for telling us of this, kind sir, and may your engines always ignite on the first try (that's what belters say, isn't it?). <3