You don’t know how long you’ve been in the cell. More than hours. Less than weeks. There are no windows, no lights, no cues to tell you what time of day it is, how much time has passed. They threw you into this dark hole and left you. You’ve started wondering if they just forgot you existed.

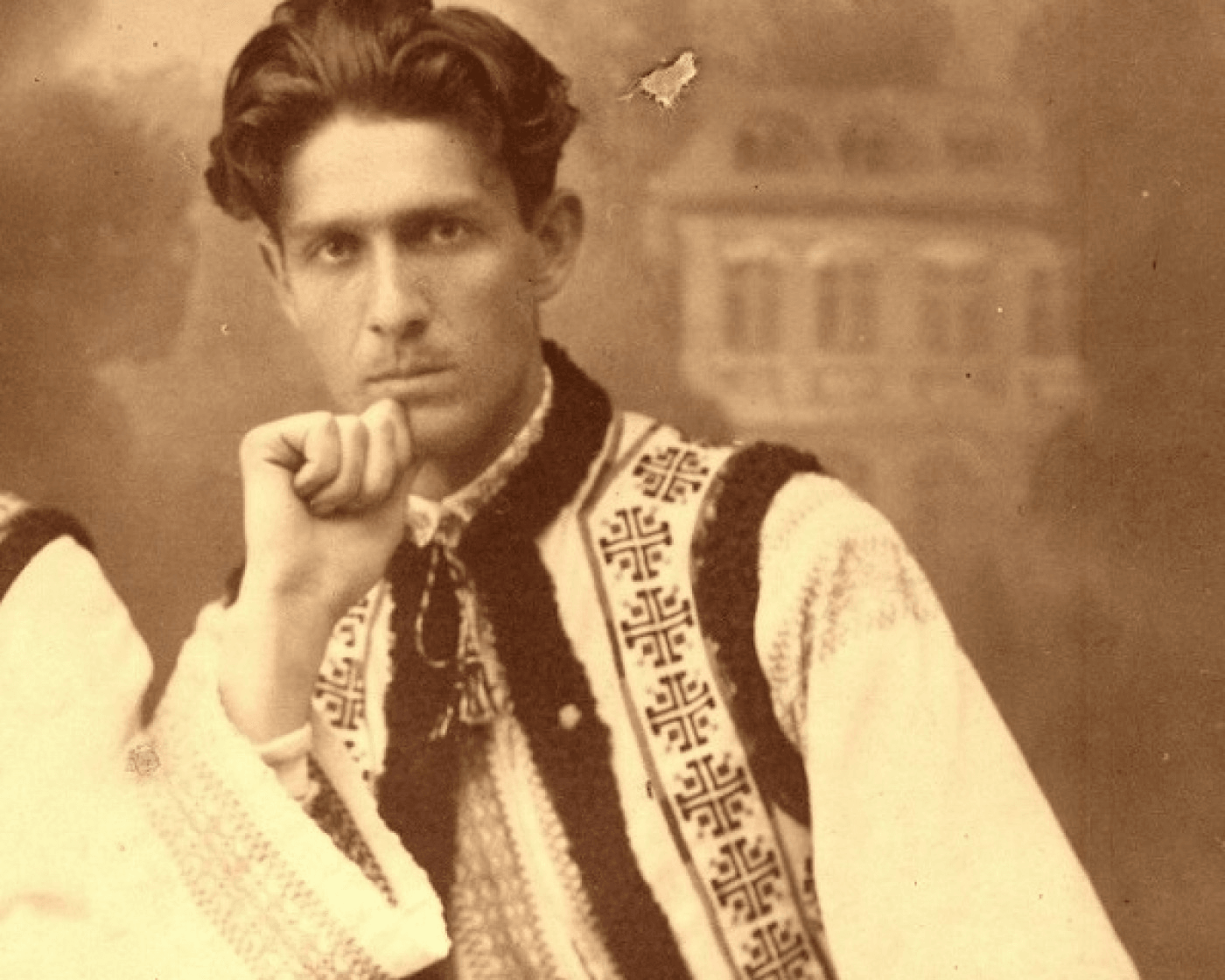

Then the guards opened the door and throw Georghe in with you. You’re overjoyed to see him. It’s been years. He’d worked as a junior instructor at the Polytechnic University of Bucharest when you were studying electrical engineering there. He was a few years older than you, but he’d been a fixture at the protests and the underground meetings, an enthusiastic anticommunist and nationalist, as so many of you, the best of you, were. You’d never been friends with him, exactly ... there was too much of an age difference. The others in the student movement whispered that the quiet, intense man had been in the Legion of the Archangel Michael, though he would never confirm or deny it when asked. You didn’t admit you’d been in the Iron Guard. Not after the communists had stolen the election, taken control of the government, the police, the army, the newspapers. So much had changed, so quickly. It still makes you dizzy when you think about it.

It’s nice to have someone to talk to, someone you recognize. For hours you catch up with one another, comparing notes, commiserating, joking, reminiscing. You were picked up at a riot, throwing petrol bombs at the police when a protest went bad, and the Securitate has been shuffling you around in their prisons ever since. Torturing you sometimes – you’ve got scars from cigarette burns. Once they hooked up a car battery to your balls. You still didn’t tell the bastards anything, you inform Georghe, pride in your voice.

Georghe disappeared a few months before you were arrested. He’d been in the mountains. Fighting with the partisans. Sabotaging supply convoys, ambushing patrols. Then their camp got ambushed by an NKVD kill team after someone ratted them out to the Securitate. They’d killed plenty of the swine, but the Russians could afford to lose men. They spent lives like water. Most of Georghe’s team were killed. Georghe was wounded – he shows you the scar on his stomach, where a bullet just missed his liver – and he spent some weeks in a prison hospital, after which they just kept him in prison. They’d tortured him too, of course. Everyone got tortured. It was expected.

It must be the better part of a day that you talk with Georghe. Before long you’ve both exhausted politics, and you start sharing more intimate details. You start telling him about your childhood, the fishing village you grew up in up in on the coast of the Black Sea ... your father the tailor, and the time he beat you for letting the horse get loose ... the time you snuck some of your mother’s polinka and thought you were going to be sick ... kindly old Father Ion, who had the largest library in the village, and always let you borrow from his collection ... the girl you almost married, before you went away to Bucharest to study.

The guards come and lead both of you down a dark corridor smelling of rust and wet stone, from which you emerge blinking into a brightly lit auditorium. It isn’t so bright, actually, just a few low-wattage bulbs buzzing on the ceiling, but it’s almost blinding to your eyes, which haven’t seen light in so long. There are dozens of other prisoners there. You even recognize some of them from the outside. The guards stand quietly at the back of the room, seemingly uninterested in intervening as you all slap each other on the back, clasping hands and greeting one another.

An apparatchik shuffles to the front of the room. He’s a small, weak-looking man, with no chin and cheeks like a hamster’s, dressed in a peaked cap. A severe, unadorned suit hangs on him like a gypsy’s badly pitched tent. His thin voice warbles across the room, trying and failing to command the prisoners’ attention, and eventually he gives up and simply mumbles his way through formulaic communist agitprop – put away the oppression of the past, join the workers’ struggle for liberation, and so on and so forth.

You’ve all heard it all before. You’re making eye contact with one another, rolling your eyes and sharing secret, mocking smiles. Some of the more daring allow themselves the occasional derisive snort when the weedy little official says something especially obnoxious. When the guards fail to do anything about this, the jokes start, heckling the traitorous little rodent. Laughter ripples across the room.

The little man smiles. Thin, cold, utterly without humour. A smile that does not pretend to reach his eyes.

He takes off his hat.

Georghe punches you in the stomach.

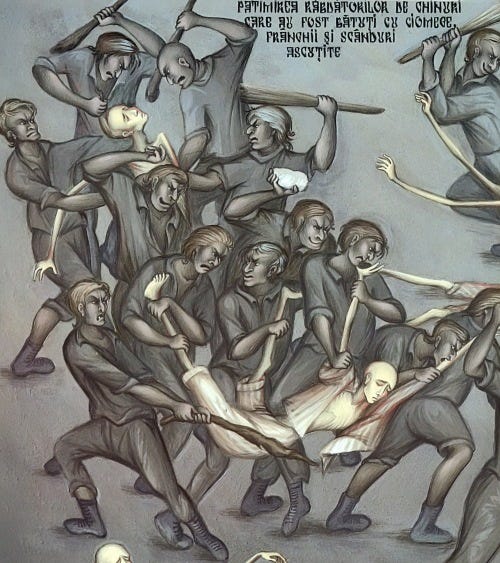

You’ve been hit before, of course. Many times. But you didn’t see this one coming, you had no warning at all, you certainly didn’t expect it from Georghe. The wind rushes out of you. You double over, breathless. Something crashes into your spine and you collapse to the ground. George starts kicking you in the ribs, in the face.

All around the auditorium the same thing is happening. Half of the other prisoners are on the ground, being beaten by the other prisoners. The guards, for the most part, stay uninvolved, except when one of the prisoners tries to fight back, at which point they’ll intervene, cracking a fist or a pistol butt across his cheek.

It goes on for hours.

By the time it finally ends there’s blood everywhere. You’re missing a tooth. One of your ribs is definitely broken.

You’re dragged back into your cell.

But there is no respite. Another man comes in, one of the other prisoners, one of the traitors that was beating your comrades. There’s still blood on his shirt. He explains to you that it’s time to sleep, and that you are to do so in the corpse position, flat on your back, with your hands folded over your chest. Failure to maintain this position will result in a beating.

You drift off, eventually, only to be awoken by a sharp crack across your shins. You were told not to move, the guard tells you.

That happens several more times during the night. When you’re finally told that you may move, to start your day, you do not feel that you have slept at all.

Breakfast is gruel – thin, barely warm. There are clumps of hair in it. It is served in a battered tin bowl.

They take you away for interrogation. The torturer knows all about your past ... all the intimate details you shared with Georghe. The torture is nothing you haven’t gone through before. Cigarette burns, electrical shocks, beatings. But the questions the interrogator is asking, these are new. He doesn’t seem to have any interest in intelligence gathering, not that you know anything useful at this point ... it’s been a couple of years since you were arrested. Instead, he seems to be fascinated by your personal life ... your family, your friends, your upbringing. He wants to know everything. When he thinks you’re being less than forthcoming you get beaten.

At one point you’re punched so hard in the stomach that your breakfast comes up, spewing all over the floor. Some of it spatters on the interrogator’s shirt. Eat it, he says. You must be joking, you reply. One of the guards smashes his fist across the back of your head, slamming your face down into the floor, into the puddle of vomit. Eat it, the interrogator repeats. Still you resist. You’re used to pain, but this kind of humiliation is too much. One of the guards grabs your arm, bends your elbow in a direction it shouldn’t go. Fire shoots through your nerves. Eat it, the interrogator repeats.

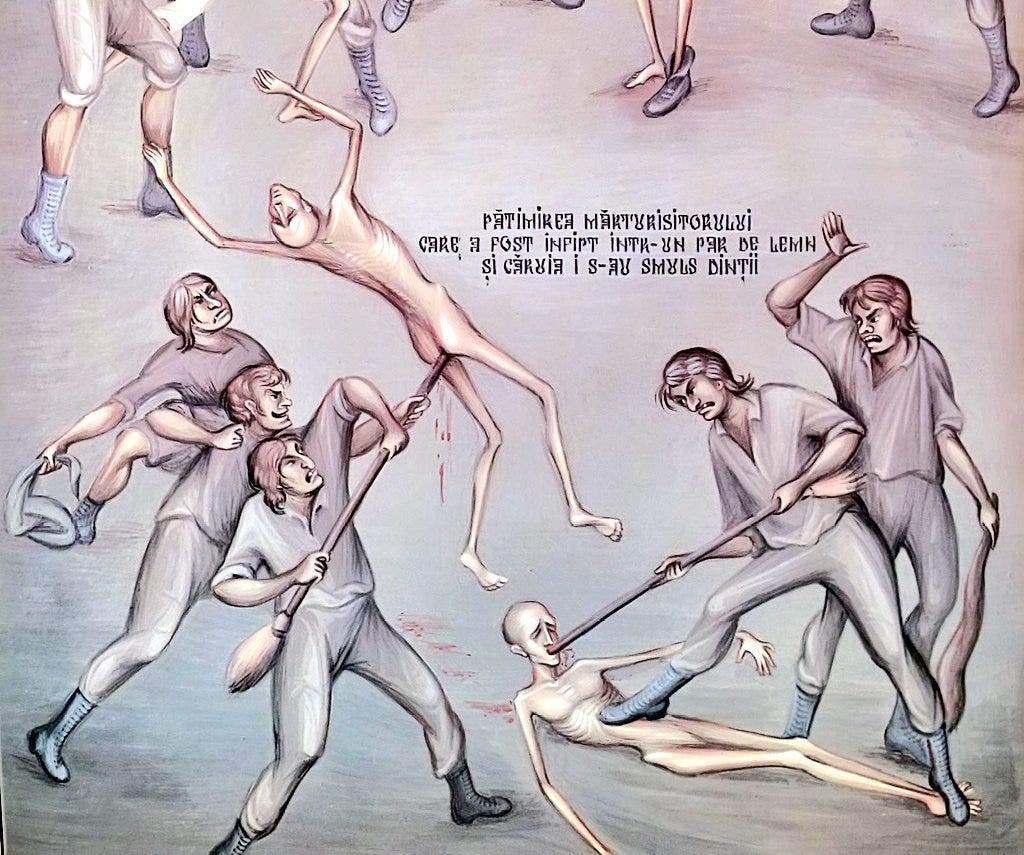

They don’t let you up until you’ve licked the floor clean.

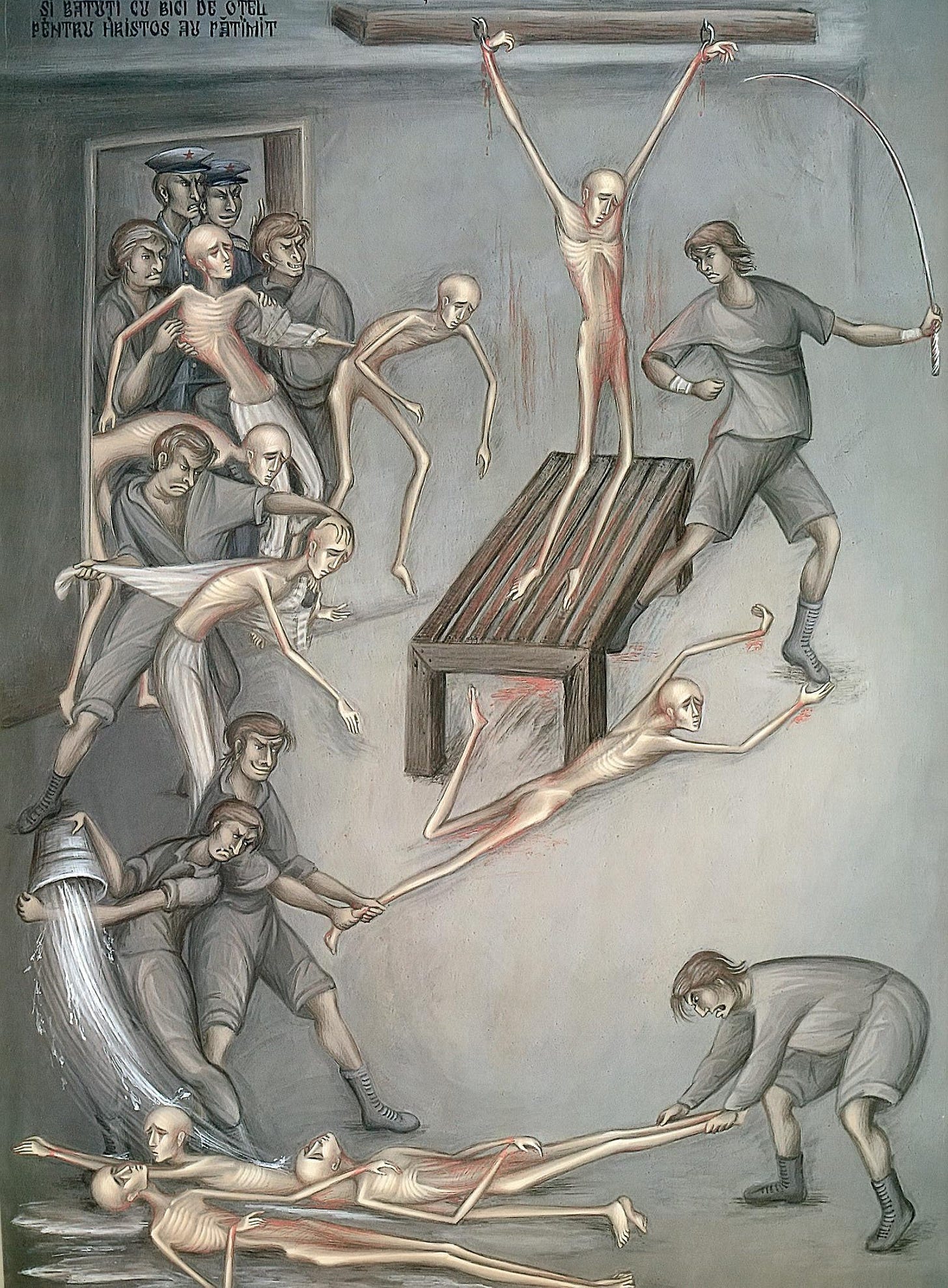

If you lost track of time in the darkness, it disappears entirely in the hell you’re in now. Your days are full of beatings and torture and interrogations, conducted for no apparent reason, not to gain any information, which you don’t have in any case, but simply because they can. Most nights you don’t sleep, but lie there silently in the corpse position, not daring to move a muscle lest the guard crack a truncheon across your shins or slap it across the soles of your feet. The battered tin you get your one meal a day in is also, you soon discover, your chamberpot. You are not allowed to wash it. Sometimes during the beatings you throw up. Other times you shit yourself. Every time you’re made to eat it. Sometimes you’re interrogated in pairs, or in groups. In those cases it isn’t your own shit they make you eat.

Sometimes the interrogator asks if any of the guards have shown any small kindnesses to you ... a bit of extra slop for breakfast, perhaps, or letting you wipe out your tin after relieving yourself, or failing to beat you when you know you must have moved when you slept, or just holding back a little bit on a beating. No, you say at first, no they’re all very cruel, very brutal, they all treat me like a beast. Are you so certain? He asks. Not even the smallest mercy? You must tell me if so. I do not think I believe you. And the torture would begin again.

Georghe, you finally say. Georghe beat me the other day when I tried to clean my mess tin, but he did not hit me so hard.

Thank you for being honest, the interrogator says, with a fatherly tone.

Shortly after that you hear Georghe’s screams coming from down the hall.

The interrogations begin to take on a strangely psychotherapeutic aspect, with the interrogator asking about small crimes you’d committed, the tiny infractions of childhood, how you felt about these, how they affected the people around you. Why did you steal your brother’s bicycle? How did it make you feel when you didn’t share your sweets with your little sister, and she cried? Did you feel good about that? Was it not cruel of you to stop writing to the girl in the village, after you went away to university? How do you think she felt? Why are you so selfish? What could lead you to behave in such a fashion? Do you really think you are a good person?

Every question is punctuated with fists, kicks, cigarette burns, pliers, electric shocks.

Why would you fidget in church? You said you thought highly of Father Ion, why would you disrespect him so? Why sneak away to play in the churchyard? You say you are pious, that you believe in God ... this God you claim to believe in, would he look kindly on this? Does this not show that you do not respect God? Do not fear him? Perhaps ... you do not believe in him after all? Perhaps you have been lying ... no do not deny it ... you have been lying, even to yourself? Can you admit this? Why would you lie in this fashion? What were you really afraid of? Surely it was not this God ... already you have said you do not really believe in him.

The guards come into your cell. One of you is dead, they tell you. He gnawed through his own wrists, like an animal. Good for him, you say, and may God bless him. That may be, one of the guards says, but the animal has not blessed you. He punches you in the mouth. He keeps punching until your teeth loosen, and then takes out his pliers. You pass out several times. You don’t need teeth to gulp down the slop they serve you, in any case. Or your own shit, as the case may be.

The interrogator presents you with an affidavit. It details how Father Ion would organize orgies in the church, at which your parents were enthusiastic participants. They whored out your baby sister to the priest, and made you engage in homosexual acts with your brother for the entertainment of the others. This will be sent to your parents, you’re told, and then published in the newspaper in your village. But first you have to sign it. Don’t you want justice? Don’t you want the world to know the truth about what was done to you?

You sign. Why would you not? It’s true, isn’t it? It must be true. You said it. Would your parents do that, though? But they’re reactionaries, enemies of the people. Nothing is too depraved. You’ve explained many times that it was only their abuse that led you to joining the student movement, to opposing Marxism-Lenninism. Scientific socialism is simply the only sane way to run a society. Therefore you must have been insane, and you were insane because of the memories you’d repressed, the horrible things your parents did...

Why would you tell such lies? About your own parents? The interrogator shakes his head sadly. Truly despicable. What a low, contemptible creature you are. Devoid of all honour, all integrity. Less than an animal.

The beatings for the rest of the day are particularly savage.

Later they tell you that your mother cried when she saw the affidavit. That your father disowned you. Your brother swore to kill you, and so he was shot, as an enemy of the people. See, the interrogator says, you have no family now. You only have us, he whispers softly as he attaches electrical leads to your nipples, only us, it’s only us, now. Now and forever.

You’re led into a room, made out in a mockery of a church. There’s a phallus standing where the crucifix would be, a tub of stinking urine in the baptismal font. They make each of you kiss the phallus. Now it is time to be baptised, they say. Your head is forced down into the piss until you feel like you must drown, and then pulled out, just long enough to gulp down a single gasp of air, before your head is pushed back into the foul basin. This happens several more times. You have been born again! The guards cry out, in mock joy. You are Mary Magdalene!

Others are reborn as Joseph, as the Virgin Mary, as Luke, as John, as the Archangel Gabriel, as the baby Jesus himself. They make you put on a mock nativity play. At one point John is made to sodomize you; at another, the Baby Jesus is ordered to take your penis in his mouth. It goes on for hours. The guards take endless joy in their creative suggestions.

Congratulations, the interrogator tells you. You’ve graduated from the first stage of the program. You’ve done extremely well. One of our best students.

You hate yourself for the feeling of warm pride that blossoms in your traitorous belly.

We have a special task for you. There is a prisoner, a very bad man, a counterrevolutionary reactionary. An enemy of the people. A menace to society. He needs to be reformed, to be liberated from all of the old ideas that imprison his mind, that tie him to obsolete notions of faith and nation. You are to help liberate him.

What do you need me to do?

To begin, go into his cell, and talk to him. Win his trust. Tell him about yourself. Ask him questions. Learn everything you can about him.

I understand, you say. You understand quite well. You don’t need to be told what will happen next.

Wonderful, the interrogator says. This is a very good thing you are doing, an important and necessary thing. But you must be strict for it to be effective! Otherwise it will only take longer to reform him. He might backslide. That does happen, regrettably. Unfortunately, when a subject backslides, he must repeat the program, from the very beginning. It is the only way. You remember Georghe? When you met him six months ago, he’d just finished his third round of treatment. He’s halfway through his fourth, now. We have high hopes for him. As we do for you. You understand what I am telling you? That you must be very strict? Very vigilant? Excellent. So, it is time for you to start your work.

When comparing the record of atrocities left by the twentieth century’s ideologies, it is easy to get lost in simple numbers. Communism was worse than fascism, many on the right will say, because communism’s body count was so much higher. Hitler might have killed millions, but communists killed a hundred million. The pyramid of skulls is incomparably heavier, and weighs down the scales of justice decisively on the side of communism being by far the greater evil.

But as Stalin is reputed to have said, one man’s death is a tragedy; a million deaths are a statistic. Raw numbers do not communicate raw horror. Statistics leave the heart unmoved.

When challenged on the relative body counts of National Socialism and Communism, leftists will usually reply that the Bolsheviks, Marxist-Leninists, Maoists, Afro-Marxists, et al. may well have killed far more people than Hitler, but that Hitler’s einsatzgruppen and death camps were still uniquely horrifying, because the Nazis targeted people for their race rather than their ideology or social class, while doing so with a bloodless mechanical efficiency that utterly dehumanized their victims.

The implication that the communists did not also do these things is tendentious – they were not at all above exploiting ethnic divisions, indeed they did so routinely – but the true reason that it is beyond the pale to wear a t-shirt emblazoned with a hakenkreuz, while a display of the hammer and sickle is unexceptional to the point of being unremarkable, ultimately comes down to emotional programming.

No one cares how many millions were killed by this dictator or that warlord. These are mere numbers, the output of cold equations, processed by a part of the brain that has nothing to do with emotions. What matters is that, for decades, our media have produced an endless stream of lurid histories, novels, movies, documentaries, and television shows depicting the horrors of the Holocaust. These images have burned themselves into people’s minds. Small children are traumatized with them at an impressionable age – made to watch Schindler’s List or read Elie Wiesel’s Night or study The Diary of Anne Frank as part of their education. The victims of the Holocaust become, not mere numbers, not decontextualized names listed on a memorial somewhere, but real people, human beings with faces, hearts, souls, dreams, families, friends, lovers, and quirks of personality ... they become, in people’s minds, friends who were abused and murdered. Thus the Nazi who murdered them becomes the ultimate beast, not a mere villain of history, but a personal enemy.

The horrors unleashed by communism, however, are never talked about in such terms.

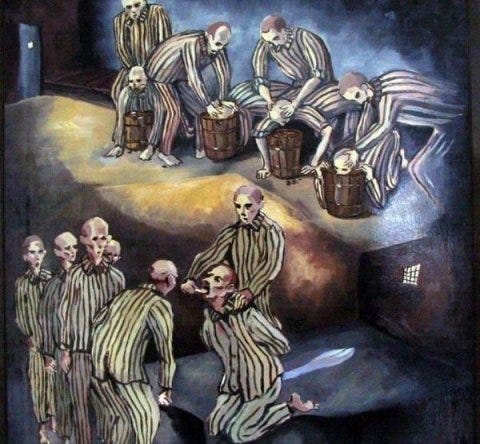

The events depicted in the opening of this essay are fictionalized, but they are based on something that really happened ... and which almost no one knows about.

The Pitești Prison Experiment ran from 1949 through 1951, in the small city of Pitești, an hour or two from Romania’s capital city of Bucharest. You can read more about it here and here, on X; the last hour of the Martyr Made history podcast, titled The Anti-Humans, provides a thorough discussion of the events at Pitești, largely taken from the book of the same name (which was smuggled out of Romania).

Romania avoided most of the fighting in WWII, although it knew its share of upheaval thanks to its extraordinarily popular homegrown fascist movement, the Legion of the Archangel Michael, also referred to as the Iron Guard. The Iron Guard were fanatical Orthodox Christians, bitterly opposed to communism, capitalism, and Romania’s authoritarian king Carol II, who they saw as entirely too friendly with Jews, of whom they were, to put it mildly, not fond. Through the 1930s and 40s the Iron Guard’s echipele morții – literally “death teams” – conducted assassinations of opposed politicians. For a brief period around 1940, they ran the country.

In 1945 Romania was occupied by the Red Army, who were technically their allies; Romania started the war on the side of the Axis, as they saw the Russian communists as by far the greater threat, but they switched sides at the end. The country saw almost no fighting and so, unlike many other Eastern European countries, Romania had not been smashed flat by the war – its physical and social infrastructure were perfectly intact. The communists wasted no time in subverting the country’s institutions. Despite godless communism being highly unpopular in the devout country – the Iron Guard actually had a larger proportional membership than either the Italian fascists or Germany’s National Socialists – the communists were successful in stealing an election in 1946. A year later King Michael I was forced to abdicate, and the country became a People’s Republic.

When one hears of a ‘student movement’, the image that usually comes to mind is a mob of young communists or some variation on this theme. In the modern context, one might picture fat women with purple hair and their scruffy, skinnyfat, weed-smoking soyboy orbiters; a century ago, one might imagine bespectacled intellectuals passionately debating the Communist Manifesto. The Romanian student movement of the 1930s through the 1950s was the precise opposite of this: it was a right-wing movement, which emphasized discipline, patriotism, nationalism, and piety. Far from rolling their eyes at the students, they were celebrated in Romania as the best of them. The Iron Guard was its most militant manifestation.

After the communist takeover the student movement took up the fight against the communists, and the communists won. The communists, however, were not satisfied with mere repression. They wanted to fashion the New Soviet Man. Their materialistic ideology insisted that human beings were infinitely malleable action-reaction machines, blank slates upon which instructions for any behavioural profile could be inscribed with the right conditioning. The nationalist student resistance of Romania provided the perfect opportunity to demonstrate this theory. If the patriotic, reactionary Christians of the student movement could be reformed into good communists, anyone could be.

And so, the experiment started in Pitești. They chose subjects who had already demonstrated resistance to torture, whose character and will had already been tested and found to be tough and durable. It was precisely the strongest that the communist psychologists intended to break, as this would provide a truly definitive test.

Thousands of young men were fed through Pitești. The numbers were not so large. The duration was not so long – the experiment was shut down after two years, not because the communist leadership were bothered by it in the slightest, but because rumours of what was happening in Pitești were circulating and threatening to cause unrest that might destabilize the fragile new regime (the experimenters themselves, including the prison warden, were later tried and executed – someone had to be thrown to the wolves).

What it lacked in scale and duration, Pitești more than made up in psychological sadism. It plumbed infernal depths that I have never encountered elsewhere in the history of mankind. The communists sought not merely to break the bodies of their subjects. Nor was their goal only to shatter their minds. Their objective was to smash men’s souls, to strip them of absolutely everything – faith, nation, family, will, self-respect, identity – that made them individual human beings. They sought to scratch out the Imago Dei.

When you think of communism, don’t think of bread lines, famines, anemic economic growth, clunky consumer goods, or ugly buildings built with substandard concrete. Don’t think of fucking statistics.

Think of Pitești.

Pitești reveals the spiritual essence of communism in is purest, most distilled form.

Thank you for reading this. As harrowing as it may have been to read, it wasn’t easy to write. Yet I feel it is important that more people know about Pitești. Communism gets an easy pass. It shouldn’t. There has never been a worse evil on the face of the Earth. We’ve shrugged it off for far too long.

There’s a second part to this, loosely connected, but this has already gotten very long, so I thought I’d cut it in two rather than inflict another 10,000 word monster of an essay on you. The next part will come out in a couple days.

As always, my boundless gratitude to my patrons. You make it possible for me to keep writing here. If you’d like to do your part to keep these missives from Mars coming, you know what to do:

By the way, I’d like to direct your attention to the Based Book Sale, where you can – for a few more days – acquire very cheap entertainment from a wide selection of excellent authors who are not beholden to the harridans of Big Publishing industry:

You must understand, the leading Bolsheviks who took over Russia were not Russians. They hated Russians. They hated Christians. Driven by ethnic hatred they tortured and slaughtered millions of Russians without a shred of human remorse. It cannot be overstated. Bolshevism committed the greatest human slaughter of all time. The fact that most of the world is ignorant and uncaring about this enormous crime is proof that the global media is in the hands of the perpetrators.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

I wonder what those deranged woke students with multicoloured hair and confused gender would make of this story. Not that they would ever read it. A hard reminder of the horrors perpetrated in the name of high moralism...beware of the do gooders!